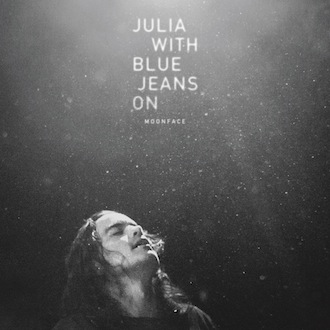

Following last year’s superb, seismic collaborative album, With Siinai: Heartbreaking Bravery, recorded with Finnish krautrockers Siinai, Spencer Krug, man of many guises – he’s formerly a member of Canadian indie big-hitters Wolf Parade, Sunset Rubdown and Swan Lake, and now recording solo as Moonface – has jettisoned that album’s grandiose, motorik sonics, opting instead for a collection of songs arranged for just voice and piano. It’s perhaps not such a surprising card to play, given that Krug’s been clear from the start that Moonface would be a constantly-changing proposition, and this latest, more classically singer-songwriterly direction proves Krug to be a master songsmith, unfurling lyrical, captivating sketches that are entirely mesmeric.

It could so easily have fallen the other way – just shy of 50 minutes’ worth of nothing but a man and his piano has the potential to be bracingly dull – but Krug is both a fine musician and a compelling storyteller.

Underneath his crisply-recorded piano-playing, which bears Philip Glass’ cinematic scope and melodicism, the pared down set-up puts an increased onus on his words, perhaps smothered slightly by the sturm and drang of Siinai’s guitars and synths on Heartbreaking Bravery. As such, it hits home just how good Krug is as a lyricist. The songs pivot on his capacity for bleakly-coloured melodrama – loss, self-destruction and hopelessness all get a look-in – but this lyrical seriousness is also crucially bolstered with the heft of biblical imagery. Although this was an unintentional theme, according to Krug, it resurfaces time and again on the record: lambs are led to altars, water is turned into wine, Abel and Cain make an appearance and, in ‘Dreamy Summer’, “the existence of an all-seeing deity” gets debated and ends up apparently found wanting. If it’s the self-dramatist in Krug that’s drawn him to these elements, it’s also his wry humour that tempers them: in ‘Everyone Is Noah, Everyone Is The Ark’, for example, he uses the Old Testament tale as a vehicle for reflecting on universalised, inevitable world-weariness, working it through to gift us the pearl of a rhyming couplet: “Everyone ends up talking to the sky/ Or looking the elephant in the eye”.

Elsewhere, he’s able to borrow from other, less pious sources: common, in some cases, heavily overused songwriter tropes, such as ‘Barbarian’s call to “Stop me if you’ve heard this one before”, ‘Black Is Back In Style’s “spot in the sun” and ‘November 2011’’s double whammy, hung around a chorus line of “baby we both know we are both crazy” followed by Krug’s urging to “let me have this dance”. Given how cliched these could sound, it’s too Krug’s credit that he manages to deliver them in such a way as to acknowledge that, then sidestep, making them seem knowing and, in the case of the latter, curiously, wholeheartedly sincere.

What rings clearest is Krug’s knack of conjuring up lines that etch themselves onto the mind long after the song’s ended. His imagery burns with startling precision, sometimes metaphorical, as in ‘Love The House You’re In’’s redolent image of the self-defeatist, acknowledging his own shortcomings, “I would like to be more for you than a ghost, lighting up in the courtyard”, at other times with the zinging specificity of elements apparently drawn from real life. The same song’s exacting observations in, “So leave the shade halfway open, leave the shade halfway drawn”, provide a different spin on a tired platitude, while ‘Black Is Back In Style’ paints a picture of folly rooted firmly in sense of place: “And we talk about the way that people are/ As we drive towards Salt Lake aware from a liquor fire/ We say how could they not have known? How could they not have known? Until we drive 50 miles too far…”.

Krug is best, though, when he sets the seemingly direct and personal alongside his ornate metaphors, nowhere better played out than on the title track. Over mournful, almost gothic arpeggios, he paints a picture of the vain grasping of songwriting, the “mad man’s game making cadences end in golden fields”, moving to a midway point where he decides to forego it all, the “anything more famous, anything more grand, anything more noble”, in favour of the Julia of the title. The music works up to a triumphant pay-off, Krug intoning “I see you there, over at the bottom of the stairs/ Obliterating everything I’ve ever written down”, again seeming to draw on real life and imbuing it with his mental narrative, a powerful double-header over music made tremulous with catharsis.

Krug started the supporting tour for Julia With Blue Jeans On with a gig at St. Pancras Old Church in London. As well as providing the ideal space for Krug’s reedy vocals to ascend into, given the album’s themes, it was an apt choice of venue, and Krug couldn’t resist nodding to this, raising a glass to God before apologising for some lyrics that He might not approve of. This toying with the idea of godliness, or the lack thereof, as well as Krug’s self-image and the “well-intentioned demon somewhere within” in relation to that, works well for him, giving him both a vehicle for his seriousness and something for his humour to kick against. Moreover, the album further proves Krug to be a fine songwriter in the fullest sense of the word. It’s the product of a chronic overthinker refining his teeming thoughts into crystalline song, forming an album that doesn’t shy away from the gravitas of grand gestures, and, more importantly, the emptiness that follows when they prove to be futile.