As hauntology becomes a matter of political debate on the blogosphere (inevitable considering the term’s roots in Derrida) I feel that this distracts from the uncanny and beautiful aesthetic value of those artists with whom the phrase first became associated. I’m thinking the Ghost Box label, Ariel Pink, Broadcast, The Caretaker, and so on. I’d be the last person to object to taking a concept and running haywire with it, but given that they’re almost all arch-fantasists, these groups couldn’t be less politically motivated. Instead, their approach to music is to be "weird" in almost the same sense as you might find the word – and world – explored and revealed in literature. Perhaps, in this context, "weird" is a more suitable term of description than "hauntology".

If we take Lovecraft being the exemplar, the weird in literature works through a distortion of reality, be that a recognisable landscape or situation. All of the aforementioned acts play with memory by throwing familiar sounds at you (often from the past) and then subjecting them to wholly contemporary devices; say, Focus Group’s rough edits and loops or Belbury Poly’s analogue/ digital confusions. The other prime obsession of many ‘weird’ acts is geography. Barring Ariel Pink, ‘weird’ music is obsessed with England and the English landscape.

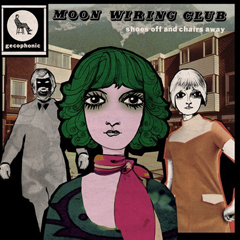

Moon Wiring Club are a more recent addition to the cannon. Their debut, An Audience of Art Deco Ears, was a sublime masterpiece. MWC have taken this obsession with locale to such an extraordinary degree that they have a huge and gorgeous website dedicated to Clinkskell, the mysterious village from where these gentlemen of music launch their temporally skewed transmissions.

MWC’s attack on time and memory comes from vocal samples, spoken word culled from lost TV transmissions, supernatural films and a probably a huge dose of Hammer Horror. The other thing that is quite startling when you listen with a certain amount of distance is how much like hip hop this sounds. It’s kind of like NWA being produced by William Blake, Kent instead of Compton. The beats are hard, choppy and slow and the space between the rhythm and melody is as much East Coast USA as anything else.

Another enormously attractive aspect of the music is a total lack of irony in what’s taking place, even if the approach might sometimes be light-hearted. This is no reflection of seriousness of intent. It has been suggested that hauntology is a kind of parallel post-modernism that creates the new from the past; a temporal interruption to that philosophical ball and chain where irony is ditched in favour of alternate histories for pasts that never existed. These in turn become the new building blocks for sound, a wealth of open horizons to which the listener is warmly invited. These artists reinstall history by interfering with it.

Moon Wiring Club’s second release is business as abnormal and is even more submersive and evocative than their debut – this is high praise indeed. The album is bookended by their best songs to date. ‘Always A Welcome’ sounds like a slo-mo rave for spectres, chunky beats and an orchestral or organ riff pitch-shifted and saturated with effects moves like a ghost through your ears. ‘Ten Years or Twenty’ is simply staggering, a voyage through darkest pastoral Britain, a sinister voice promising "apples for everyone" and then what sounds like dialogue is multi-tracked and treated to such ecstatic levels that the spoken word becomes song. It’s utterly captivating, a huge wave of eerie sound underpinned by chiming bells of doom and warm expansive flute. Another highlight is ‘Strangers to the Music’ which has a melodic faded grandeur, laughing voice echo from nowhere whilst a solemn voice invokes "all things must be as they were before" while another moans "help me".

But all in all, every second is a portal. These twenty-two tracks make for a sublime and spooky trip from start to finish as orchestras, woodwind and harpsichords all get manhandled by the technologically-savvy ghosts in the machine. The second it starts you’re instantly transported to this other world and you don’t leave until you’re allowed to – never has this green and pleasant land sounded so uncanny.