Like the notoriously single-minded captain conceived by his famed literary forebear, Moby has spent the past fourteen years chasing the success of the great white whale known as Play, his game-changing 1999 release that effortlessly merged the genres of electronica, soul and pop into a singular, commercially-verdant masterstroke. That record would not only score a platinum certification, but all eighteen of its tracks eventually earned licensing deals for television, movies and commercials – a first in modern music.

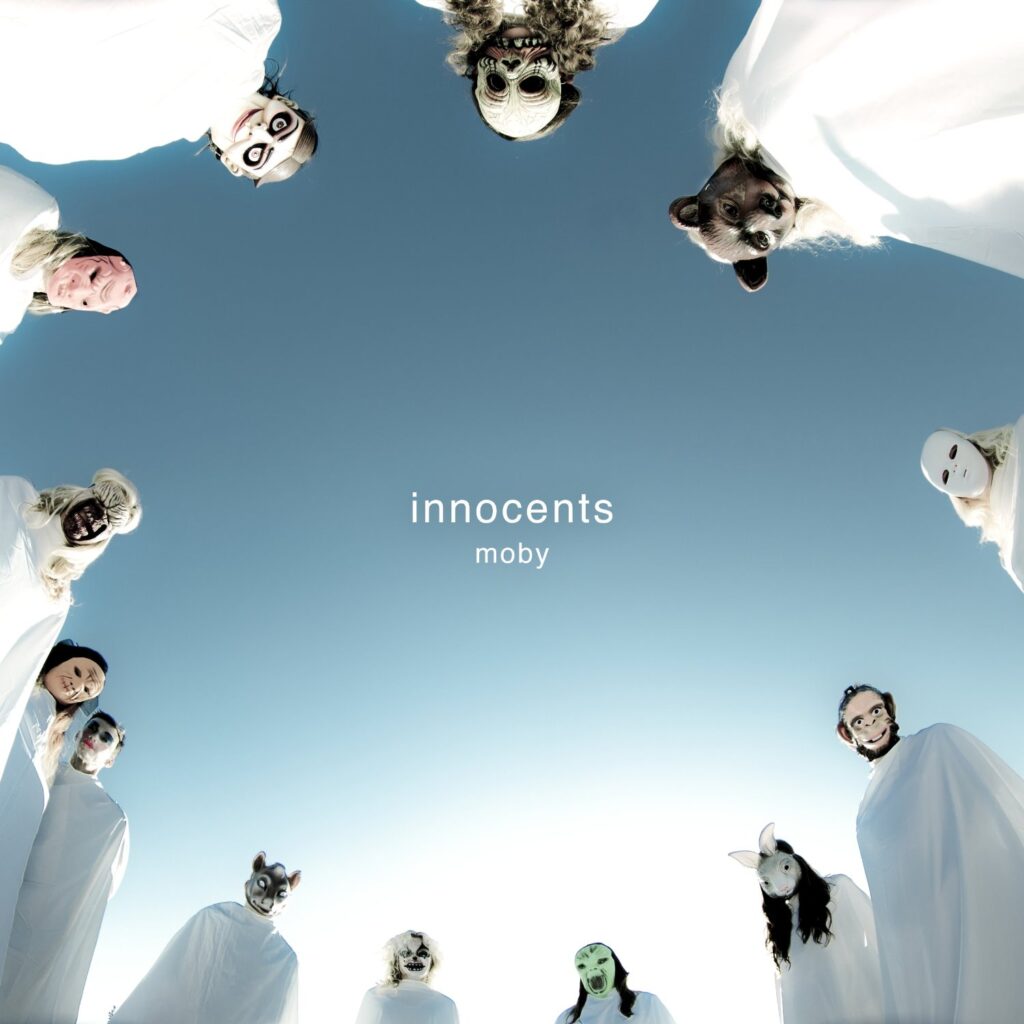

And yet in the weeks leading up to the release of Moby’s eleventh full-length studio outing, the artist has identified Innocents as the album that he has waited his entire life to write – a curious, if not outrageous statement from a man who has enjoyed a career with not one but two golden ages. Despite these successes, Moby himself claims that, “[I]t’s 2013 and I’m 47-years-old, and so a) very few people listen to the eleventh album made by a 47-year-old musician; and b) very few people listen to albums. So if there were a Venn diagram of that, the number of people who might actually listen to this album from start-to-finish probably could be counted on two hands.”

Glib self-deprecation or authentic self-awareness? Likely liberal doses of both, yet notwithstanding the artist’s pessimism, Innocents easily rivals the platinum-certified Play, making a legitimate case as his finest work to date.

As with his previous albums, the twelve tracks mine a broad array of influences, including soul, techno, pop and of course, electronica, all steeped in lush, ambient textures and muted, lo-fi beats. Opener ‘Everything That Rises’ showcases Moby’s tried-and-true formula- a spare rhythmic pattern expanding as layers of moody atmospherics and sparkling melodies are progressively added until the track erupts with a dramatic crescendo. In this sense, Innocents draws from the artist’s trademark motifs while conveying a relaxed confidence all but absent in his first ten albums, such maturity embodied by smoother melodic transitions and less-cluttered spaces between notes.

Although no two tracks sound alike, Moby’s adroit sense of melancholy pervades nearly every one, save for the pulsating and deliciously filthy ‘Don’t Love Me’ (featuring his longtime vocalist Inyang Bassey), with its steamrolling piano intro and sleazy bended guitar notes lasciviously stretched across the beats.

Whereas previous albums have featured almost exclusively female guest vocalists, the new effort introduces a quirky trio of male vocalists, including Wayne Coyne (The Flaming Lips), Mark Lanegan (Screaming Trees) and folk artist Damien Jurado, whose breezy and relentlessly catchy track, ‘Almost Home’, offers the record’s purest dose of unfiltered pop. Lanegan’s inclusion (the haunting ‘The Lonely Night’) confirms Moby’s longstanding commitment to experimental songwriting, while Coyne’s contribution, ‘The Perfect Life’, drapes morbid lyrics about addiction in a shimmering, singalong anthem, establishing Moby’s sustained affinity for dark thematic contrasts.

Two collaborations with Canadian singer-songwriter Cold Specks push the record over the goal line, with an intimate, late night confessional ‘Tell Me’ and the album’s first official single, ‘A Case for Shame’, a velvety groove swathed in ambient keys, luminous harmonies and Specks’ signature bluesy drawl.

For most, Play provides the only point of comparison for Moby’s sound, and those searching for another ‘South Side’ or ‘Bodyrock’ will find themselves bitterly disappointed, no doubt carping over a perceived lack of inspiration. Point missed. While Play offered instant gratification, the myriad rewards of the new album emerge through repeated listens, as deceptively simple song ideas begin to reveal stunning melodic structures embedded within the smooth, flowing textures. From its funereal ballads to its hook-infused jams, Innocents is uniformly satisfying and catchy as hell, suggesting a fascinating possibility – if this is the album that he has waited his entire life to make, then at the grizzled age of forty-seven, Moby is only now entering his prime.