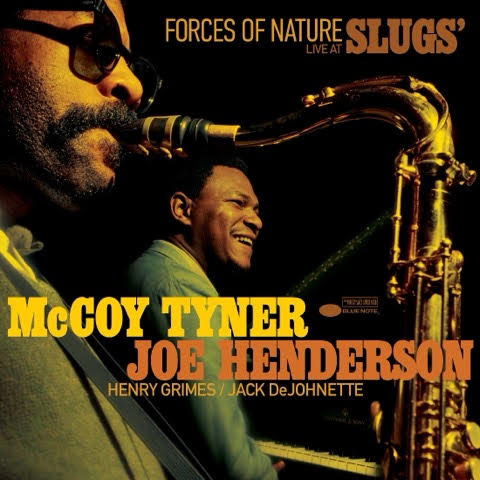

In recent years too much of the jazz world has focused on vault discoveries from decades past rather than the innovations and developments in improvised music occurring right in front of our eyes. Nostalgia and marketable names frequently trump today’s best recordings, but sometimes a document is unearthed that not only contains a stellar performance, but which also fills in historical blanks. That’s certainly the case with Forces of Nature, a jaw-dropping live recording from 1966 that drummer Jack DeJohnette kept in his personal archive nearly six decades. The searing performance from the legendary New York venue Slugs’ – a hothouse for music in transition that closed in the aftermath of trumpeter Lee Morgan’s 1972 murder in the space – captures four of the greatest jazz artists, all in the midst of change, finding common cause as they straddled tradition and revolution.

A year before the session pianist McCoy Tyner had left John Coltrane’s quartet, DeJohnette, 23, had recently arrived in New York from Chicago, starting his fruitful association with Charles Lloyd; bassist Henry Grimes had already planted one foot in the mainstream vanguard with Sonny Rollins while working with Albert Ayler and Don Cherry; and tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson had already revealed his freedom-seeking proclivities within the Blue Note mainstream, with Tyner as his pianist of choice. The bulk of the album rips open tunes by Tyner and Henderson, retaining their form but summoning a level of sustained force and fiery yet unbelievably rigorous interaction. Henderson takes dozens choruses over the course of twenty-six explosive minutes on his ‘In ‘N Out’, which opens the recording, stoked by Tyner’s driving livewire vamps (and, sometimes, the deliberate absence thereof) and DeJohnette’s massive attack, triangulating between Tony Williams, Elvin Jones, and his own evolving aesthetic. Grimes functions as an essential junction between past and present, underlining the changes while unleashing unstoppable propulsion.

There’s a gorgeously tender reading of the ballad ‘We’ll Be Together Again’ along with a relatively concise account of Henderson’s ‘Isotope’, but the biggest thrills come in the extended pieces, such as the spontaneous minor blues later titled ‘Taking Off’, where the musicians tap into the pure expression and improvisational exchange of that era rarely captured in such unadulterated form. Yes, these musicians were all involved with or impacted by the New Thing, but we almost never get to hear it unfold without the limitations of the studio or live documents of the time. Even at their most explosive, the performances don’t neglect the full scope of jazz tradition, moving seamlessly between form and freedom, and fueled by a collective creativity that’s impossible to miss.