"There’s some things I just can’t tell you ’bout, honey." This unassuming lyrical fragment permeates the very fabric of Matana Roberts’ Mississippi Moonchile. Not only are the words uttered by Roberts numerous times throughout its duration, but they seem to capture the entire aesthetic – the ineffable feel – of this remarkable album. Taken from an interview that the New York-based saxophonist conducted with her grandmother, this snippet of speech surfaces throughout the latter’s scattershot reminiscences of her childhood growing up in Mississippi. It’s as quotidian as it is suggestively elusive: is it simply a discarded turn of phrase, arising from the natural ebb and flow of everyday conversation? Or does it carry greater significance, a wistfulness in the face of half-lost memory?

The centrality afforded to this phrase throughout Mississippi Moonchile suggests the latter, with Roberts’ nimble sing-speak examining the words from all angles – elongating, shortening, disrupting the flow of syllables. As such, the words are bestowed with a near-mystical gravity, forming the nexus from which all else on the album unfurls: Mississippi Moonchile emanates from a place where memory becomes nostalgia and nostalgia melts into fantasy.

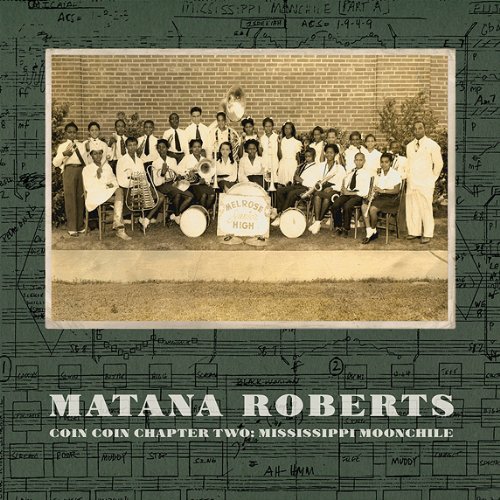

Mississippi Moonchile is the second in a projected twelve-album cycle entitled Coin Coin. And throughout the project thus far, Roberts has used her music as a medium through which to explore the liminal zones between lore and history that define the ways in which we understand ourselves in the present. Primarily interrogating her own sense of identity as an African American woman, Roberts calls upon numerous other voices – from her family’s history, her culture’s mythology – to create not historical documents but living artifacts of collective cultural memory: simultaneously disorienting and exhilarating in their chaotic multiplicity.

The first album in the Coin Coin series – 2011’s Gens De Couleur Libres – was brutally visceral in its direct confrontation of America’s history of slavery, the knotted atonality of its free jazz embodying the stark horror relayed by Roberts’ lyrics. Mississippi Moonchile, by contrast, is airy and mellifluous. In the place of vivid images of sexual and racial oppression, Mississippi Moonchile‘s lyrics are instead laden with hazy nostalgia, painting vague snapshots of life in the Southern states in the mid-twentieth century. Roberts’ ensemble has downsized from a ramshackle big band to an economical five-piece, the unity of which is broken only by the occasional intrusion of an operatic tenor. And her voice on the saxophone, once caustic and incendiary, has mellowed to exude elegant melodic contours.

Yet, that’s not to say that Mississippi Moonchile‘s comparable restraint has resulted in an album of less dramatic potency than its predecessor. Rather, the evocative majesty of this record lies in that which Roberts allows to remain unsaid and unplayed. The music is hesitant, cautious, at times surging with momentum and luminous melody before quickly collapsing in on itself, unable to sustain such a state of unchecked abandon. And the same fraught lyrical themes of racial and gender inequality that were so dominant on Gens De Couleur Libres weigh heavily on Mississippi Moonchile, although they’re often obscured behind its contented, almost joyous, facade. Roberts’ spoken soliloquies are abstract and erratic, juxtaposing the words of her grandmother against passages from the Bible and Civil Rights speeches. Fleeting, incomplete references to the reality of racial inequality in mid-20th century Mississippi appear amidst the stream of consciousness ("Can you say ‘yes sir’, n****r? Can you say ‘yes sir’?"), only to be instantly dispersed as the music skitters off in other directions (Roberts breaking into song, "I sing because I’m happy, I sing because I’m free").

It is during such moments that Mississippi Moonchile appears to be striving towards a meaning, a significance, that lies perpetually out of reach: just like her grandmother, Roberts has so much that she can’t quite articulate, opting instead to conjure only ambiguity, to speak only in impressions. With Mississippi Moonchile, Mantana Roberts’ Coin Coin project continues to resonate with the complexity, multiplicity and, occasionally, the horror of the contemporary world, whilst remaining steadfast in its belief in the ability of individual voices to rise – albeit momentarily – above the noise.