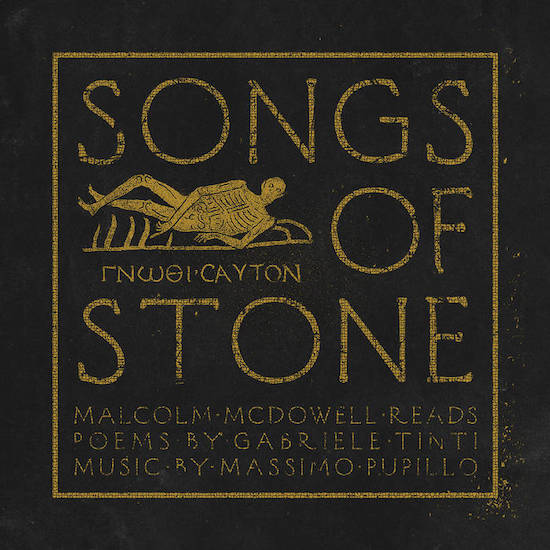

An album based on the elegies and laments of Gabriele Tinti, and narrated by Caligula himself, Malcolm McDowell, Songs of Stone is a wonderfully weird affair, rich with mythos and ritual. Composer Massimo Pupillo (of Zu fame) does a fine job of weaving Tinti’s texts into a moody, ethereal soundscape, a world of deep bass swells and distant, shapeless vocal chants. At times a little too obvious in its rendering of new-age tropes, the album risks, on occasion, sounding like the generic soundtrack to a roleplaying game about dragons – though thankfully a latent sense of grim foreboding elevates things to a far more interesting plain.

With McDowell’s vocals subject to a variety of electronic processing, and Pupillo’s propensity for glacial, droning textures, it’s within Songs of Stone’s less ostentatious moments that things come to life. Tremolo strings waver atonally at the fringes, whilst a submerged brass band meander through a half-hearted dirge. Distant percussion strikes like thunder across an alien world. It’s stirring stuff, a claustrophobic cloud muted only by the somewhat odd choice of having McDowell’s voice placed several hundred times louder than the rest of the instrumentation – which certainly brings out the tonal grandeur of his signature drawl, though risks disturbing the otherwise evocative horizon.

Melding avant-garde drone with horror aesthetics and a healthy dose of ambience, the album single-mindedly explores the macabre colours of its source material, with Tinti’s prevalent themes – death, depression, decay – reflected in the unsettling torpor of its sonic accompaniment. Though oriented around the voice, its text is used sparingly, with long sections of tense inactivity – abstract loops of thunderous bass, and repetitive choral syllables, all mired by a lack of meaningful definition – breaking up any sense of a defining, logical narrative.

McDowell is, as one might expect from a man who has made a career of playing larger than life anti-heroes, an intimidating presence, his performance ripe with intensity and grit. In contrast, however, Pupillo allows the music to be pleasingly subdued, with its sounds not only doused in reverb but at times shorn of any sense of timbral character. The slow, methodic chord progression that underpins the work – a smattering of musical progression in any otherwise Dead Sea of the static and the sparse – is buried so thoroughly within the mise-en-scène that it barely registers, lost to the thick layers of formless strings.

Clocking in at just over twenty minutes, Songs of Stone never risks outstaying its welcome. For an album so utterly dedicated its signature gloomy aesthetic – a murky bliss at once unnerving and a touch hammy – Tinti, McDowell and Pupillo demonstrate a restraint seemingly at odds with the playful dramaturgy of their material. In doing so they have crafted an album that’s not only a rather pleasant listen, but a fair bit more enjoyable than the sum of its impressive, if thematically florid parts.