Martin Creed recently commented that not working with sound and music as part of his artistic practice, "would be like I’m ignoring half of life." As anyone familiar with his art will know, Creed has spent the past 30 odd years methodically and impishly exploring every detail of human existence: from Blu Tack to puking – from the flicker of an electric light to the gait of an Irish wolfhound. The fact that these visual, physical and exceedingly tactile things comprise so much of his work, and yet he considers them only half the world, goes something toward proving that Creed is as much a musician as he is anything else and that this album (his second proper) is as far from being a side project as you can get.

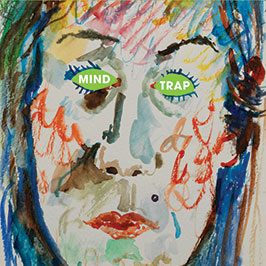

It kicks your preconceived ideas of the artist out of kilter too. Most likely, his 2001 Turner Prize winning ‘Work 227’ (The Lights Going On And Off) will remain the thing for which he’s best known (those shuddering filaments somehow epitomising the perceived lunacy of contemporary art); but while it accurately captured his enduring sense of humour, it has caused him to be wrongly pegged as an exponent of minimalism. Creed is anything but. He is a motely paint daubing, neon monolith building, giant turd shitting, orchestra commanding maximalist. Recorded in London, Chicago and the Czech Republic Mind Trap transmits simple emotions on rousing scales. Rather than the chugging riffs & repetitious texts that he’s previously produced, Mind Trap brims over with actual songs – melodies and sequences that flutter outside the lines; not loose scribbled accidents but joyful, emotive bursts.

Take ‘New Shutters’ for example, a gentle romanza in ¾ in which Creed berates a window (in Italian) for blocking the view to his lover; or ‘Kid Yourself’ which teases with stark, unaccompanied repetition of the song title, before a house-y stab of female backing vocals chucks you one way and then a rhythmic bass line the other. You could legitimately dance to ‘You Return’ and ‘Pass Them On’ draws a direct felt-pen line between Creed and Ivor Cutler, whose influence (incidental or not) bleeds through in absurdities, expletives and the genuine tenderness of his delivery.

The second half of the record gives way to three extended orchestral pieces. Creed has dabbled in classical composition before, but instead of toying with the nature of the material – likening a scale in G to a pile of Elastoplast or bricks – he has pulled off something deft and dramatic. On paper, their Cage-ian playfulness might be more evident, but in practice those schemas quietly recede in favour of an uncluttered and gently grandiose classical music that’s genuinely impressive.

It’d be inaccurate to say that Creed had let go of systems and sequences entirely – his lyrics are cyclical and simple – but it’s formulaic in the best way, like three chord punk – a communal uproar, gleeful and energising in repetition, rather than seeming predictable or stuck. Mind Trap is a triumph of feelings over ideas, of making sounds bigger and more mobile than the spaces (or heads) that contain them.