“When I was young, I was really quite scared of the dark. I think my parents taught me to be and I remember the deciding thing was, I turned around and said: I’m going to go to the woods at night and walk into the darkness and embrace it and if I die, I die”.

So speaks Coil’s late Jhon Balance, from David Keenan’s recently reprinted England’s Hidden Reverse, in words which make manifest the human fear of the dark and how best to conquer it. The darkness, we are told, is this visceral entity which seeks to consume us, overwhelm us and eventually destroy us. We are scared of the darkness as children lest bogeymen and wraiths come howling towards us from deep within its cowled malicious core.

As hopefully happily functional adults, we are taught to not let the darkness dominate us, to not give in to it. It feels like contemporary culture has engaged a tritely simplistic reading of light versus dark, a Teletubbies retelling of the New Testament proclaiming that good and pure light should vanquish the forces of the dark which crawl across the planet’s surface like Hooded Claws to be cancelled out and abnegated by superheroes shining all-pervading lanterns. “Are you winning?”, we say to each other, “Are you looking towards the light?”. If not, we are regarded as failed and fallen wretches.

It’s a cliché but a truism that we need the darkness to let the light shine through, but we also need it just so we can linger awhile in the shadows, hidden from view and safe from being forced to interact with the everyday. Noise music, in its self-defeating bellow of wilful refusal, could also offer a constructed space in which to remove oneself, walled in by starless ferocity and blank-faced chasms. Yet noise, in its most volatile and harshly combustible capacity, can now find itself supported by Arts Council grants and fleshing out BBC Radio 3 sponsored orchestral festivals. Perhaps that’s a good thing, that we can place such extremities on display for mass public consumption. We have appetites; we need to acknowledge the balance of light and dark, noise and calm, while remaining ever aware of their symbiotic partnerships.

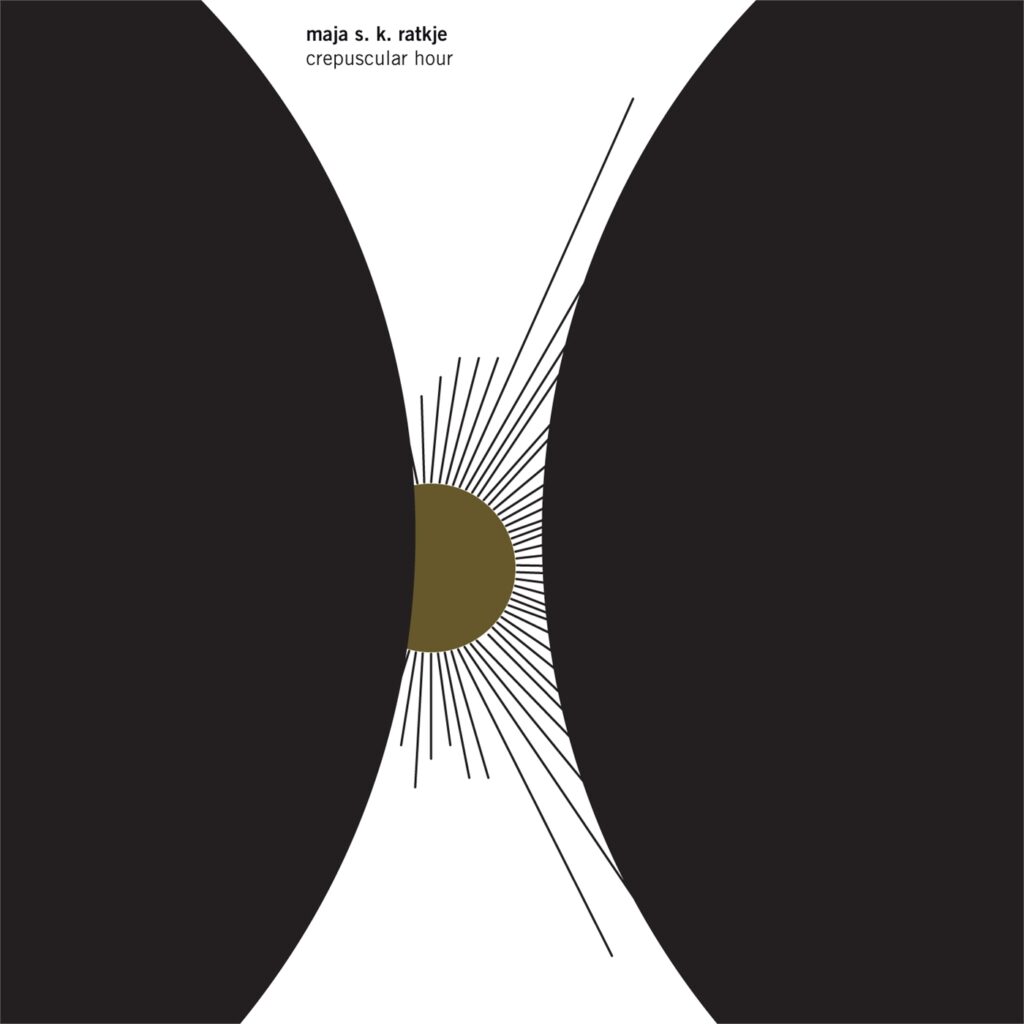

Norwegian composer Ratkje‘s mesmerising Crepuscular Hour seeps through the liminal cracks between light and dark, the spiritual gloaming during which living bodies and minds change their patterns of behaviour. Recorded during the 2012 Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, it is a piece for three choirs, three noise musicians and church organ. It begins with an almighty sharp intake of breath, like the oxygen were being sucked out of a vast space as if by one violently conjoined sigh, and it is these gathered voices which predominate throughout the performance. Based around texts from the Nag Hammed Library, a collection of early Gnostic gospels discovered in Egypt in 1945, the choirs augur portents of chaos and battle while sounding scarcely human, or at least not the work of individual human beings. Here, as with the most extreme choral work of Ligeti, we have the voices of living people turned to mass invocation of barely suppressed terror and hysteria in the face of cataclysm.

The noise-based contributions from musicians such as Stian Westerhus and Lasse Marhaug further amplify the intensity, adding texture but never overshadowing the vocal work, and while Crepuscular Hour varies in volume, at times dipping down to meditative hush, the focus and determination held within the piece never lets up. As the church organ kicks in for the final sequence, layering on another dizzying level of pressure, it becomes impossible to consider any notions of the gentrification of noise within classical composition. Ratkje’s work of dense magnitude is straining at its leash, the darkness determined to slip its bonds and be set free amongst us. It becomes essential to ward off any lingering pain and fear, to allow this physical presence to thunder over us unhindered. The hour will always find us in the end. Be on your guard!