Luther Russell has melody running through his veins. He probably has key changes instead of most normal bodily functions. Middle eights? He shits ’em.

Good breeding is the key here: Russell is the grandson of legendary lyricist Bob Russell, who collaborated with Duke Ellington and Quincy Jones and whose credits include ‘Brazil’ and ‘He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother’ to name but two; he’s also grand-nephew of the equally respected Broadway composer Bud Green (‘Alabamy Bound’, ‘Sentimental Journey’ etc) and has a whole family tree of similarly creative individuals. Luther has honed his craft as a producer and sideman for Sarabeth Tucek and Richmond Fontaine among others, as well as writing and recording his own material in similar rootsy vein.

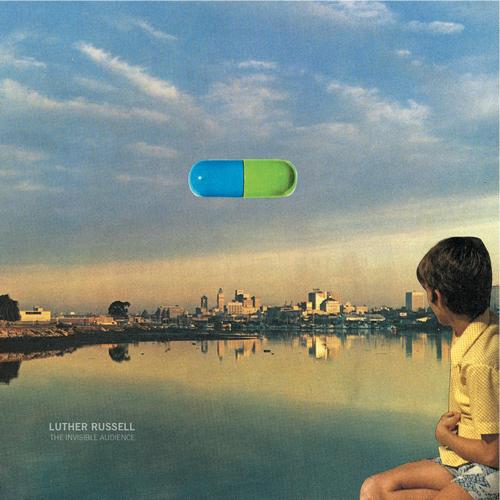

So it’s kind of a given that The Invisible Audience – Russell’s fifth solo LP – is firmly in the classic tradition. Reviewing it on the basis of whether it breaks new ground (it doesn’t) would be missing the point, as it makes no claim to be avant-garde. The question instead is whether it can still sound fresh despite being constructed from essentially the same ingredients as a million other records. It’s whether it tweaks the formula just enough to drag an emotional response from a listener inured to decades of manipulative rock and pop clichés. It’s whether it balances craft with spontaneity, leaving just enough space for the listener’s own imagination to take over and weave their own story between the notes. This is the invisible audience: you and I, the only ones who can make a record like this complete and meaningful, by bringing it into our lives and investing each song with a little piece of our own memory, our half-remembered dreams and private regrets.

Not every song can carry this emotional weight, but Russell knows exactly how to work it. One effective element is to communicate a kind of yearning, and indeed a sense of loss infuses each of the 25 songs on this sprawling double album in one way or another. It’s in the raw glam rock of ‘Sidekick Reverb’, a producer’s paean to damaged and distorted speakers as a metaphor for dysfunctional love, as much as in the Elliot Smith-like walking blues of ‘Better Off Dead’ or the understated but quietly devastating ballad ‘In This Time’. Love lost and the passing of youth are the explicit themes, but between the lines there’s also an unspoken mourning for a vanishing America, a nation founded by ambitious immigrants like Russell’s own forebears, chasing a dream of freedom and a simplicity of life that’s long since been sold down the river by the big corporations and powerful cabals.

Between the gutbucket blues of ‘A World Unknown’ and the woozy psychedelic melancholy of ‘Motorbike’, between the rolling Buddy Holly rhythms of ‘Ain’t Frightening Me’ and the staggering bar-room rasp of ‘Long Lost Friend’, you can almost hear the clang of trolley buses and taste the sawdust of old-style saloons with brass rails and spittoons, where western gentlemen with gold pocket watches observe the lengthening shadows on the streets outside.

American writers like John Fante and Charles Bukowski haunt rueful laments like ‘Broken Baskets’, and this feeling is particularly enhanced by the brief instrumental interludes that punctuate each side: the piano blues of album opener ‘Still Life Radio’, the banjo-picking ‘Dead Sun Blues’, and especially the blurry nostalgia of ‘109th and Madison’. All conspire to add depth and perspective when placed next to a melodic, harmony-laced rocker like ‘Everything You Do’, which sits confidently down between The Beatles, Big Star and Teenage Fanclub and asks them to pass the sauce, or ‘Traces’, which feels immediately like an old friend – Evan Dando’s less drippy cousin? Or someone you met through Gram Parsons?

The album ends with a powerful version of Charley Patton’s ‘Elder Green Blues’, by which time Russell may not have transcended his influences but has at least earned the right to hold his head high beside them. A masterclass in harnessing several generations of popular songwriting craft, it’s Russell’s cracked and weary vocals that ultimately give this album its soul, and let the listener in. Which is why Russell’s audience won’t stay invisible for long.