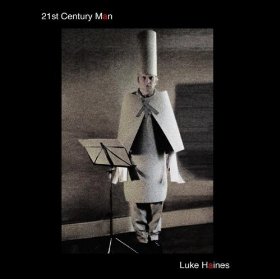

The recording arrived in a plain manila envelope, accompanied only by an unsigned postcard. On one side was a faded map of Sussex, the dreary English county I now call home; on the other, a blurred, black-and-white photograph of an outlandishly dressed man — by inference, the author and voice on the recording — claimed by the caption to be the notorious twentieth century art criminal, agent provocateur and anarcho-dipsomaniac, Luke Haines.

I slipped the disc into my machine, and pressed play. It certainly sounded like Haines’ work: there was the trademark lyrical turning of particular rocks in order to watch the bugs crawl out from beneath; the characteristic glam-fuzz stomps; and the deceptively saccharine acoustic ballads, betrayed only by that unmistakable rasping whisper of a voice, "equal parts sandpaper and gin," as one paper had put it in his obituary.

For Luke Haines was dead. He had died several years ago — of boredom, apparently, although scorn might be nearer the mark. The music scene was a quieter, duller place for his absence, though many high-placed industry personages were secretly glad of his passing. The reaction of the general public was one of widespread indifference: but what could one expect, in these days of instant downloads and awards for glorified ringtones, when shabby provincial oiks and stage school guttersnipes were presented as the authentic poetic voice of the proletariat? Haines’ time had been and gone, alright. But what, then, was this: a message from beyond the grave? A sick joke? I checked the postmark on the envelope: Buenos Aires. I was on the next flight.

Bad Vibes, Haines’ posthumously-published memoirs, was already remaindered in the airport bookstore. Clearly there were elements of our recent past — the dishonourable conduct of the Britpop Empire in particular — that we, as a nation, were still unwilling to come to terms with. Even at the end, Haines still had the knack of needling the wrong people — or the right ones. If he was still alive, he was very wise not to set foot on sovereign soil again.

Could it be that Haines had faked his death and fled to foreign climes? I listened to the recording again: the lengthy, seemingly autobiographical title track certainly suggested he was still alive, and moreover that he had left his former preoccupations behind him, in the century to which they belonged. It even concluded with the teasing declaration, "I’m an exile in a foreign land, I’m a 21st Century Man."

And yet there was something a little too pat, a little too easy about the whole thing, as though the recording were a parody, a deliberate facsimile of Haines’ trademark M.O. All the pointers were there: references to obscure yet apposite cultural figures of a certain period (‘Peter Hammill’, ‘Klaus Kinski’); arch, "I’ve been to art school" song titles that never quite lived up to their promise (‘Russian Futurists Black Out the Sun’); celebrations of the seedy and the roguish in our national character (‘Wot a Rotter’, in which a vicar is caught out, "bashing the bishop"); but if it was a put-up job, it was certainly done with style, even when the aforementioned title track threatened to turn into Denim’s ‘The Osmonds.’

With these thoughts in my mind, I left the terminal and sought sanctuary from the stifling tropical heat in the darkness of a nearby bar. Down some insalubrious backstreet I found just the place, its dingy walls hung with photographs of half-forgotten entertainers and fugitive criminals. Pride of place was reserved for those who managed to be both at the same time. A fellow sat alone at a corner table caught my eye: he had the unmistakable appearance of an ex-pat Englishman, albeit of the singularly eccentric and old-fashioned type one only ever encounters abroad these days. He was dressed in a white linen suit and Panama hat, and sported the most ludicrous ginger sideburns and handlebar moustache. I had the impression of a chap formerly given to great passions and vigorous idealism, but who had deliberately allowed himself to go to seed. I signalled the waiter and ordered two Pernods: one for myself, and one to be delivered to the gentleman in the white suit, with my compliments.

Elsewhere on the recording, Haines — if it were he — seemed to be playing it surprisingly straight. The opening number, ‘Suburban Mourning,’ described London’s outlying boroughs with an uncharacteristic wistfulness, denying tabloid clichés of wife swapping and Satanism as one waited in vain for the Hainesian twist that never came. Even the missing child was returned safely: now, you never got that with The Auteurs. Ray Davies would have been proud of ‘Love Letter to London,’ which bade good riddance to the middle classes who treated the city as a playground in their youth, then fled to the shires when it came time to settle down. Likewise, ‘English Southern Man,’ an answer record of sorts to Haines’ own ‘Leeds United,’ and an apologia for the Home Counties and their denizens: "we are executive saloon car drivers, we are the real outsiders." At times the irony seemed to mask a deeper sincerity, as if, in exile, Haines could not resist a genuine affection for the land of his birth.

Was the whole construct merely an extended farewell note, a final re-stating of his grand themes, a summing-up before leaving? Was it a last will and testament laid down before an uncaring world, a shedding of skins prior to another reinvention? Or had he merely run out of things to say? Maybe I would never know. I looked over to where my countryman had been sat, but he was gone; nothing remained save a half-drunk glass of Pernod, and a faint scent of exotic cigarettes, gradually dispersed by the ceiling fan creaking overhead. As I listened, I thought I caught the melody of a scratchy Rubettes record playing on an old Victrola, and someone laughing, distantly, from beyond the paper-thin walls.