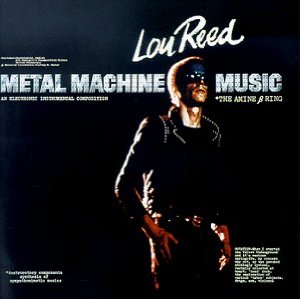

The enduring infamy of Metal Machine Music speaks volumes about trad rock’s antipathy, for all its noisiness, towards noise per se. Four movements of sustained, squealing guitar electronics, it was assumed to be some sort of "Fuck You" to RCA. This was 1975. Granted, it was years before the onset of Sonic Youth, Merzbow, Wolf Eyes, My Bloody Valentine and the partial acceptance of feedback, drones, "chaos", relentless static interference as valid means of rock’n’roll expression. However, it was years after Stockhausen, Ligeti, John Coltrane’s Ascension, Sun Ra’s Cosmic Explorer, John Cage’s Williams Mix, and well over half a century after the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo’s noise intoners. But none of these had impinged very much on rock’n’roll consciousness, in an era when even Kraftwerk were considered outré. Hence the critical stupefaction, the assumption that this was a petulant, spectacular act of sabotage by grumpy Lou, a violent, extended scrawl across his record company contract. Reed himself muddied the waters with his sleevenotes in which he at once expressed sincerity about MMM while also suggesting it was not an album anyone could or should actually sit through, himself included. Over the years, he would oscillate mischievously between celebrating and disowning it, depending on his mood at the time.

Taking Lou at his word, Metal Machine Music can be considered as a piece of work, a "composition", especially now that it has been legitimised and vindicated, with an orchestral treatment by the Berlin ensemble Zeitkratzer. As a composition it takes its cue from a remark by Andy Warhol; "why does the record have to end?" Indeed. While this piece doesn’t "progress", and takes you nowhere, it feels like an extract from an infinite process, as if it began long before the album commences and will continue long after the album has concluded. It isn’t ambient – it demands to be attended to, while offering nothing other than its own, ceaseless outpouring. Its squall of electric waste product, generated by amps, distorters, tremolo units and modulators, feels initially homogenous. Do an ear-squint, however, and you can pick out a variety of imagistic, perhaps imaginary detail – tiny, sparking furies, molten, breakaway lumps, decaying notes, bereft of melody or song structure, whose fitful, downward progress you can trace like individual raindrops on a windowpane during a heavy shower.

However, there remains the suspicion that this is "accidental" music – the difference between Jackson Pollock and the mere blind hurling of paint across a canvas. Others have, before or since, worked in the medium of ostensible "noise" but in a meticulous, sculptured way, with very precise, conceptual ideas about their intentions and their outcomes. This feels broader, vaguer, gestural – crank up the amps, open the sluices, let it flow, call it art. It’s possible to find things in this music – as a perverse method of relaxation, like the gush of a roaring tap, or as an index of rock’n’roll feedback, which is perhaps how Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore took it. But rather than be considered some sort of unacknowledged ground zero moment for noise rock, or as an "ultimate", it might best be taken as a tear in the fabric of rock history which functions as a gateway to more evolved and advanced sound adventures beyond the left field.