The weather can get bad in Brighton. Party Central by the beach in summer, certainly, but when the rains come it’s like monsoon season; the winds howling in off the downs or the channel, or both at once, and the sea and the sky merging in grey as the gulls screech pitifully in the maelstrom.

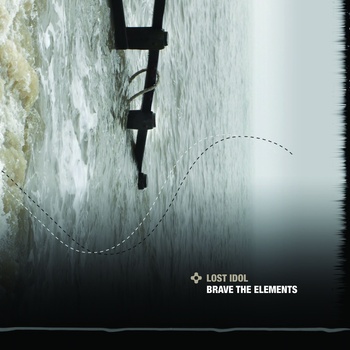

James Dean – who calls himself Lost Idol to avoid confusion with that other lost idol of the American silver screen – is a Brighton-based music producer and entrepreneur, head of the boutique Cookshop label and occasional creator of sublime electronic music of his own devising. His last full release was 2006’s Utters from a Cluttered Mind, a sun-streaked psychedelic affair that drew comparisons, and a support slot, with Caribou. Four years on, he’s back with a darker, more abstract and reflective record, and the change of season is signalled not only by the title, but by the sleeve image of a churning, dreadnought-grey sea swallowing a partly-submerged jetty, the edges of the picture fading to black.

Dean has said that he deliberately moved away from the more song-based creations of his last album, deciding to cut out the harmonising vocals and references to sunshine psych that seemed to be his trademark. Instead, Brave the Elements opens with the hard glistening edges and arid percussion of ‘Lightwerk’. The title is an obvious pun, maybe suggesting just how easy it is for him to combine the tin-can-and-a-few-wires electronica of Kraftwerk’s ‘Radioactivity’ with the stadium-bound synthesiser sheen of early Simple Minds, thus nailing the prevailing zeitgeist without even breaking a sweat. He leavens the standard Krautrock 101 apache beat with a smidgen of swing, allowing for some sexy hip action on the dancefloor rather than just the old Showroom Dummy stomp, and the result is actually pretty irresistible, as well as gently subverting the current trend of paying increasingly-derivative homage to all things German and motorik.

Having made his point however Dean shifts gear dramatically on ‘Jar Guidance’, as descending darkwave synths and half-step beats craft an ominous setting for a melody line that uses the same keyboard sound as Air’s ‘Sexy Boy.’ Indeed, the main reference points of Brave the Elements seem to be the laid-back electronica of the late nineties, when Brighton, at least, seemed to be grooving happily through one long hot summer to the sounds of Moon Safari and Mezzanine, Homework and Music Has The Right To Children. But on Brave The Elements those sounds- those elements, if you like- are filtered through memory and worn away by experience and rain. This is an autumn or winter album certainly, but shot through with a yearning for simpler, more hedonistic and warmer times, trying to recall their spirit, but summoning up only pale ghosts instead.

‘Beesmouth’, named perhaps after the Hove bar frequented by bohemian creative types of a certain age, sounds almost like a cut-up of those period Portishead and Massive Attack albums, collaged into overlapping and unrecognisable new patterns. Ghostly female vocals swim to the surface like reckless late-night skinny dippers, watching the lights on the shore flicker and smear as they peak on the last good ecstasy of the millennium. We seem to pass through the skeletal, burnt out remains of Brighton’s West Pier to the ghostly clanking and rusty scrapings of ‘My Drone Stirs in the Summertime’: a woman’s voice sings wordlessly in the distance, beyond the lapping waves, a haunted echo from another time. The plainsong chants of ‘Molten Snow’ suggest the Beach Boys at their most baroque, acid-ravaged and alone- and I seem to remember that Pet Sounds was a popular comedown record in those days- before the loops of scratchy, downtempo, stoned funk kick in.

‘Peace for Joseph’ brings us back to the present day, the responsibilities and mature joys of fatherhood, with a wordless lullaby of clockwork beats, fuzzy synths and circular acoustic guitar arpeggios. Then ‘She Summons Demons’ buffets and scours like an easterly gale, shaking the windows and rattling the frames. James’s only sustained vocal performance occurs on the aptly-named ‘A Sorrowful Thing,’ where something about his voice and the melody suggests the spare, detached melancholy of early Tears for Fears. Sounding like a bruised choirboy wrestling with sudden spiritual disillusionment, James’s voice makes you hope he’s not abandoning more song-based structures for good. And as the winds and the sea spray return on ‘Slow Slow Stop,’ the view is obscured once more, and the window we’re looking through is grey with clouds and condensation, the beach below abandoned and cold. The parties of summer and of youth fade to distant memory; the seafront cafes are closed for the season, the carousel is packed away. So many friends no longer with us. Backache and grey hairs, occasional tremors and short-term memory loss. Sombre cello tones bring the album to a close. We turn away, back in our lonely room once more.