As Supersonic’s founder Lisa Meyer told tQ earlier this summer, it’s getting harder and harder for a festival like hers to exist, with physical space being squeezed by developers and costs soaring, all in the face of indifference from a local government that in a just world would be promoting events like this as jewels within Birmingham’s cultural crown, rather than a niche inconvenience. The last-minute forced relocation of festival’s marketplace, its beating heart, from central venue XOYO to the nearby Zellig complex, encapsulates that fact, as does Friday night’s first-time use of a local Irish bar, Norton’s, after XOYO was double booked. More than ever before, there is a sense that Supersonic is being forced to constantly think on its feet, to adapt in order to keep afloat.

Nevertheless, in the face of mounting difficulties, the festival still manages to not just survive, but thrive. It could even be argued that the tougher things get in the city around them, Supersonic’s power increases in reaction.

This vitality, you sense, is thanks to two things – firstly, the unbroken sense of community among the crowd, who are as friendly and inclusive as it comes, buying entirely into the festival’s wider DIY ethos. Secondly, the programming itself, which is faultless.

There was not a dud to be found on this year’s bill, which makes the task of narrowing down our favourite sets from the weekend a difficult proposition, but nevertheless, here are five of the finest that tQ witnessed at Supersonic 2025.

Water Damage

Water Damage’s two drummers sit centre stage, facing one another. Around them loom two guitarists, a bassist, a violinist and a bass clarinettist in an uneven horseshoe. The seven musicians count Swans, Spray Paint, Black Eyes, USA/Mexico and more eaze among their collective credits, and are billed as a ‘droning supergroup’. That pedigree shows, but in breadth rather than intensity. Anyone can push the volume to its max, but it takes something rarer to create a sound like the one Water Damage do here. The percussionists hold back for the opening five minutes while the players around them establish a noise that envelops you from every dimension, booming deep and searing high, anchored by a simple plunging bassline. Sometimes all seven move as one, subconsciously swaying as if sailors at sea, and at other points they diverge, firing off in every different direction. This is drone cubed, a sound so all-encompassing that once the rhythm does fire up – a relentless and repetitive thud that remains unchanged for the next hour – it’s as each strike of a drum is creating a ripple within the fabric of drone spacetime. From within the maelstrom, shapes emerge, some real and some hallucinated – is that clarinet or the sound of a squeaky gate flapping back and forth in a hurricane? How is it physically possible that I am hearing a Gregorian chant from an entirely instrumental band? There are to be many drones across this weekend, but none so absorbing as this one.

Rún

When tQ arrives at XOYO, a few minutes into a set by Rún, the trio of voice artist and filmmaker Tara Baoth Mooney, Nurse With Wound collaborator Diarmuid MacDiarmada, and drummer / sound designer / engineer Rian Trench, like a number of acts at this year’s festival they have settled into a drone. Unlike the others, however, rather than settle there, ploughing deeper and deeper into a single furrow, with the emergence then disappearance of an energising rhythm, it quickly becomes apparent that they are a more restless proposition. Hauling riffs, haunting synths and churning rhythms come and go. One minute they’re drifting off on a freeform psychedelic voyage, and the next they’re diving headfirst into a lolloping glam rock stomp while lights flash around them in rapid-fire between red and blue. Mooney is one hell of a vocalist, shapeshifting between barks, howls, aloof spoken word and limber free-form poetry; at one point she’s banging a cooking pot and yelling “STRIKE IT” in time with buzzsaw guitars. This is music that keeps a listener firmly on their toes, the kind where it sometimes feels as if not even the band themselves know what’s coming next – and it is spectacular.

Witch Club Satan

Describing themselves in their promotional material as actual witches, Norwegian trio Witch Club Satan walk onstage as lights plunge the O2 Institute into darkness and murky choral vocals resound over the PA, carrying burning sage that they slowly, ritualistically hand out to their crowd. Dressed in elaborate goat-like headpieces and white robes that expose their breasts, on the surface it is all highly theatrical. It is the kind of premise that requires a performance of absolute intensity in order to be effective rather than kitsch – high risk, high reward. Fortunately, the trio deliver something beyond absolute intensity, a performance of quite staggering power, and the rewards are manifold. Their brand of black metal is rapid and razor sharp, while they frequently shift into more meditative ambient sequences and striking choral singing. The band’s dynamism is more impressive still given that bassist Victoria Røising is heavily pregnant with twins. “Today there are five witches onstage,” she declares before the aptly-titled ‘Mother’, where drummer Johanna Holt Kleive steps up to centre-stage for a shift into grungier territory. After a brief intermission they return wearing nothing at all save for long black wigs, after which the energy – already relentless – becomes that little bit more visceral. After a third costume change they are among the crowd, whipping them up into a boiling sea into which guitarist Nikoline Spjelkavik can crowdsurf. Yes, they lean into the theatricality – at one point Røising is literally bowing her bass guitar with a sword – and there is light as well as dark; as Spjelkavik reminds the crowd at one point, “it’s OK to dance”. And yet, the strength of Witch Club Satan’s performance means that it all feels in service of a greater message – a raging resurrection of those before them (witches or not) who have unduly suffered, and those who are doing so today. An explicit link to the ongoing slaughter of Palestinians – “Silence is a crime / no mercy for genocide” is delivered with particular power.

Backxwash

There can be so much power packed into one of Backxwash’s instrumentals – the booming beat and chopped up vocals of ‘9th Heaven’ for instance – that by the time she actually starts rapping, the expulsion of energy can be absolutely overwhelming. The Zambian-Canadian rapper and producer’s music draws frequently from periods of personal crisis, the force of will required to overcome them, and the mixture of pride, sorrow and strength that comes amid the aftermath, and each bar is delivered with the frayed urgency of a performer able to summon back every part of that emotional gamut. Performing entirely alone onstage, she is transfixing, whether wrapped in the fug of ‘Dissociation’, where the emptiness of addiction is laid bare, or on her knees for the rich melancholy of ‘Only Dust Remains’, which concerns her eventual resolution, she says, to become “comfortable with death”. It is in the final verse of the relentless ‘History Of Violence’, however, where all that inner turmoil is projected outwards – lyrics, which are projected onscreen, turning to an unflinching attack on those silent in the face of war and genocide, with direct reference to the unimaginable suffering in Gaza – that is the most powerful moment of all. More of a purge than a mere performance, her encore of straight-up thrasher ‘Devil In A Moshpit’, whereupon she jumps into the audience to mosh alongside them, allows for a well-earned moment of straight-up joy.

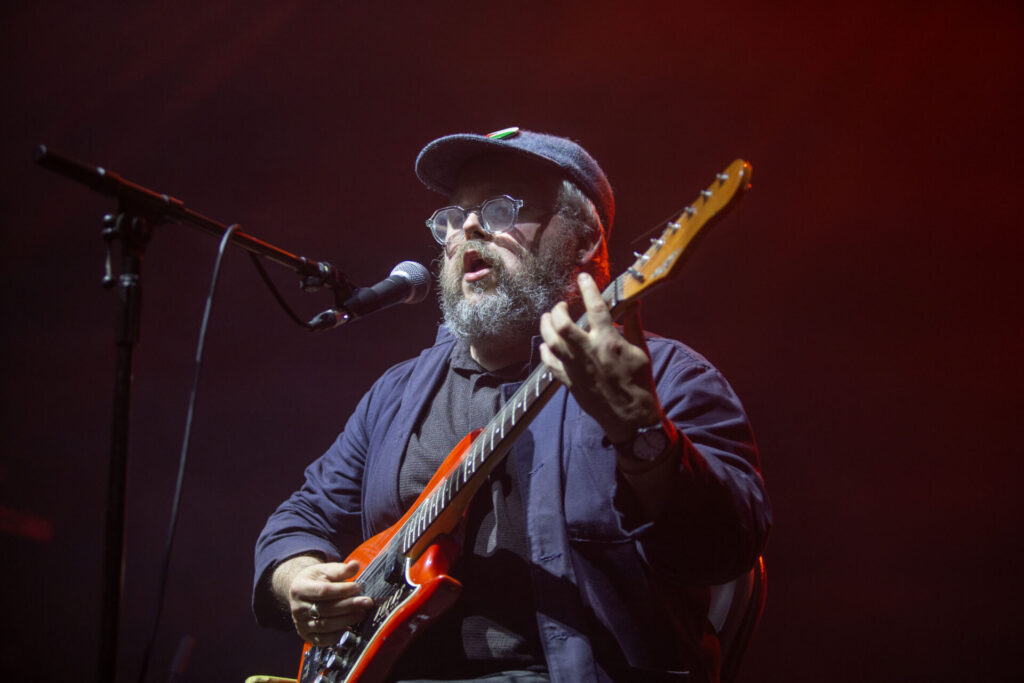

Richard Dawson

Richard Dawson tells a packed Sunday night crowd that he views his first performance at Supersonic, well over a decade ago, as one of the jumping off points for his career. Today, he, along with drummer Andrew Cheetham, walks onstage to the kind of hush that anticipates a returning hero. He begins with ‘The Almsgiver’, his a capella composition – in the style of a traditional ballad – about a mother seeking her incarcerated son. The song has long been a fixture of his live sets, but here the human emotion at the story’s core rings louder than before. Perhaps that’s due to the way his latest album End Of The Middle centres our shared humanity so clearly, delving into its little joys and sorrows, its repeating cycles and the attempts to break them, and drawing out something profound from the everyday. Music from that record dominates the setlist – ‘Gondola’, about a grandmother reflecting on her regrets and remaining hopes; ‘Bolt’, about a lightning strike interrupting domestic normality; ‘Boxing Day Sales’, about a catch-up chat where deep sorrows poke through the cracks of small talk. All are subtly, but deeply affecting. Between songs Dawson projects an easy charm, but then instantly shifts energy when playing. A tale of how he believes a recent Achilles injury to be an act of divine pagan punishment for eating a Greggs pasty while visiting ancient ruins, for instance, is the preamble to an utterly frantic, heavier-than-record rendition of ‘Jogging’ (whose line about “the atmosphere ’round here growing nastier” rings hard after a summer of far-right flag-painting thugs dominating the news cycle), while he changes a final lyric to refer to Medical Aid for Palestinians (he also wears a bage of the Palestinian flag on his hat). Elsewhere, older cut ‘Black Dog In The Sky’ resounds with sweeping hallucinatory beauty, and a cover of the late Michael Hurley’s ‘Wildgeeses’ is as moving as any performance I can think of witnessing. The whole performance treads the delicate line between lightness and depth that has characterised a lot of his recent work with total precision, that is until a closing rendition of ‘Black Triangle’ rips the handbrake from its socket, Dawson and Cheetham descending into a ferocious extended space rock freakout. This is the musician’s last show for a while, he tells us – one hell of a way to sign off.