Like Matt Johnson I came of age at a time when popular music took itself very seriously, arguably far more so than it does now, to a point where it was treated as an important social and political force even by the grown up squares who did not like it. That is not to say that there are no serious musicians around today, or important cultural figureheads, only that music has ceded its centrality in daily life to technology, been shorn of its societally transformative potential, and that for all its innate value, is one form of entertainment amongst many others, squeezed between Apple Arcade and Apple TV. The very existence of a website like The Quietus – run, read, and written by passionate enthusiasts, with its focus on the present (and not the glorious semi-recent past) – is an exception, rather than typical of the attention and respect musicians are currently afforded. I write this not only because watching The The takes me back to a time when performers’ utterances were pored over as much as their records, when society was still getting used to pop music and pop music its power over that society, but why a figure like Matt Johnson is, if anything, more divisive now than he was when I first encountered him, when I was a pretentious 11-year-old boy.

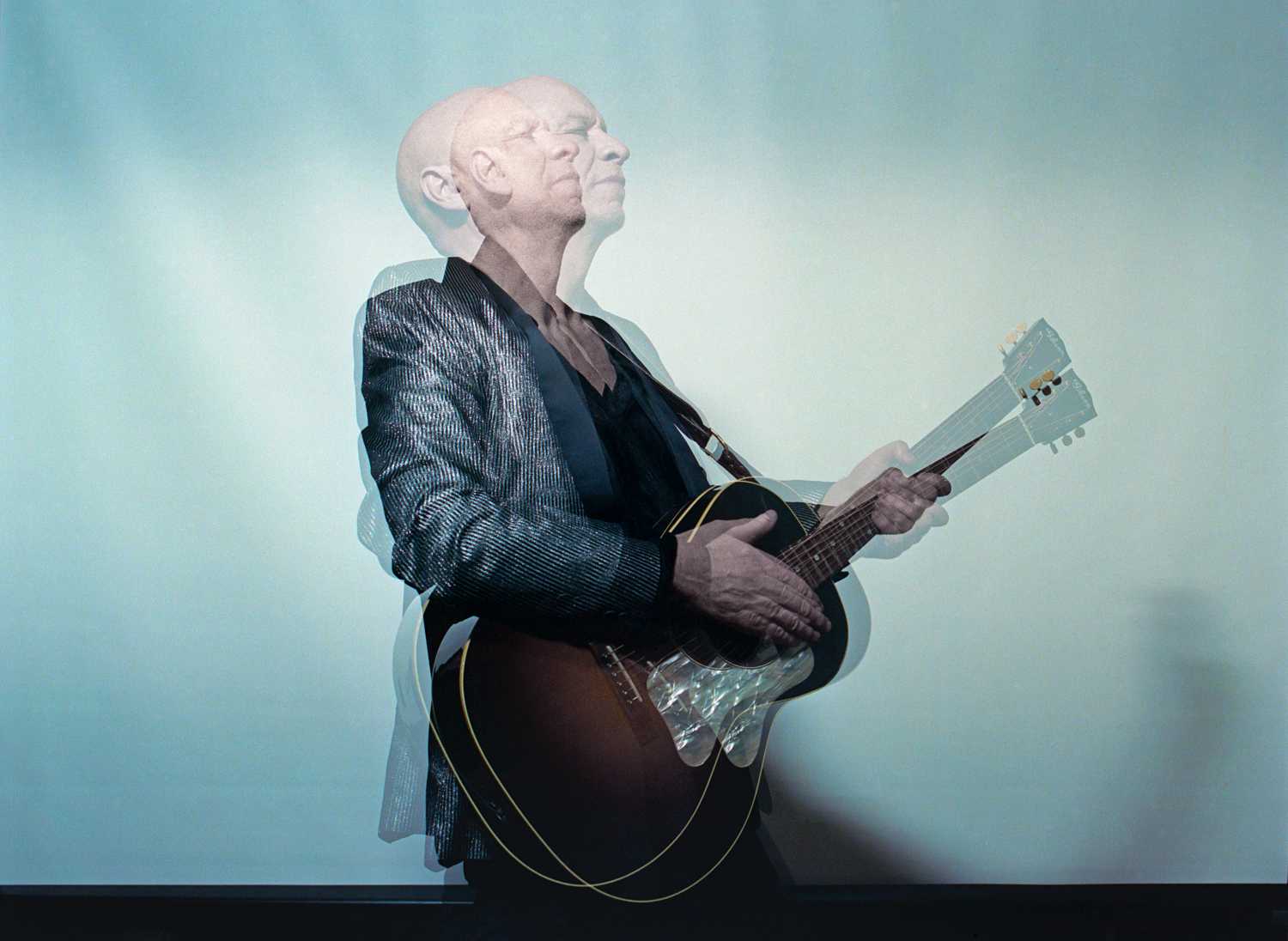

The division between those who approve of Johnson, and those that he is absolutely lost on (which judging by the audience tonight, may be breaking on generational lines, as the demo-graph is basically the same as a Paul Weller gig, which as a superannuated mod is no insult in my book) is not the one I had in mind. For me the dividing line was always between those who love Johnson madly and those that do so with a few reservations. That love is not based on nostalgia for all our yesterdays, but on still taking Johnson at his own self-possessed estimation. A man who directed a video where he was strapped to a cage at the helm of a boat on hallucinogens in a Hannibal Lecter style mask steaming down the Amazon, is never going to be lacking in confidence or suffering a failure to take himself seriously. Yet to still treat what you are doing as precious, when the cultural conversation has moved on, and people have stopped noticing, is the measure of anyone’s sincerity. And on tonight’s evidence, Johnson has not wavered one bit. Nothing he does in this two hour performance, I sense, is ‘just’ or ‘only’ music for him.

Like all ageing persons who are slowly beginning to register the fact, I forget the uneventfulness of the past, and recall the excitement, my early enjoyment of The The inseparable from the intense and delicious anticipation of what tomorrow might hold. My first encounter with them (I am going to use The The and Matt Johnson interchangeably, out of respect for the truism that if it’s “him and your granny playing bongos”, then it’s The The), perspicuously enough, was not a musical one. It was the graffiti in nineteen-eighty-six that seemed to be all over the walls and bridges of West London and its outer environs (or possibly in just three or four places I kept seeing?), announcing no more than “The The”, the two words casting a spell over my imagination. This mysterious entity seemed to be already out there in the world looking for me, or having found me, waiting for me to discover it. Shortly after that I heard Infected on one of the Hits compilation tapes, squashed somewhere between Alexander O’Neal and Level 42, and my connection to the modern world was made.

Looking back, this was an era where music seemed to control the flow of time itself; the gaps between albums were the way temporality was broken up, how individual years derived their separate identities and meaning. In this sort of context an outspoken iconoclast made a whole lot more sense than an introvert that might take a 25-year gap between albums without any discernible change in style. Fast forward to now, and whilst I thought Matt Johnson was just one of these types of artist, it turns out that he is in fact both, his musical template hardly having changed at all since 1993’s Dusk, but the gap between then and now running to decades. Moreover, were it not for the passing of time, I might not be writing this at all, as by my late teens I had already got it into my head that I might have outgrown The The. Johnson’s heavy handed didacticism, sometimes indistinguishable from self importance (and a tendency to repeat and hammer his strongest lines into the ground) began to strike me as unsophisticated (I should have known, as that’s exactly what I was), even as the songs that epitomised this habit (The Beaten Generation’) sat beside ones (‘Beyond Love’) that moved me as much as anything I had heard in my life (and even now want played at my funeral). So while I may never love Johnson’s heavy hand, I eventually came to appreciate it again, as putting things boldly and baldly is often more moving and necessary than beating about the bush, especially as I grow older and more impatient with evasive parables and emotional decoration. Lines like “My life is halfway through /And I still haven’t done / What I’m here to do” (itself written a quarter of a century ago) are pretty much what goes through my head in a Terrence Malick style internal voice over at least once a day, and rare is the night where I don’t hear the same voice emote (something along the lines of) “our lives will teem with love and regret / I hope you remember the things I can’t forget.”

Tonight Johnson’s artistic comportment, that of a solitary genius with insomnia in an open plan flat in the big city, picks up from where he last left off on his 2017 comeback tour. Compared to his early experiments with beats and synthesisers, his current band are highly accomplished, but tending towards solidity over innovation. His philosophical ambition however, is undimmed. The set consists of songs that seek wisdom and some modest mastery over the experiences they describe, and that, like sermons, aim to be sincere meditations on life and death, in the most positive sense. With characteristic assurance Johnson warns the audience that they are in for the new album, Ensoulment, in its entirety, served up straight and without frills, before a second half of the show that they “can dance to”. As there may be people here keen to get their teeth into the greatest hits and not much else, and as nothing on Ensoulment (his first top 20 album in over 30 years) could be described as uptempo, there is an element of living dangerously in arranging the evening in this order.

Beginning quietly makes a number of things clear about Johnson’s song-craft that an avalanche of strobes and percussion might obscure. The political numbers and diatribes (the very literal ‘Kissing The Ring of Potus’) which tend to proceed like voice overs for a documentary on the last days of civilisation, do not, as I used to think, come from a different part of Johnson’s brain to the more obviously personal material. While it is tempting to conclude that the man who sings “if you can’t change the world, change yourself” has given up on one intention to embrace the other, in actual fact “the world” is no more than an outward projection of an inner projection. There is objective truth out there that Johnson’s narrators find it hard to grasp (“we can deny reality but not its consequences”), while his naive and romantic realism, as well as jagged paranoia, can turn political songs intimate, and intimate ones political. Indeed, the stately arrangement of ‘Potus’ comes off like a disappointed love song.

Sombre, but never depressing or overwrought, Johnson sings like celebrating existence is one of the most rational (creative) responses to life, and that at 63, he appreciates having been spared long enough to recover from his mistakes. No one who grew up in the capital, struggling to know what happened to all the corners form Marble Arch to Tottenham Court Road, can fail to hear the wistful disbelief behind ‘Some Days I Drink My Coffee By The Grave Of William Blake’ – “where do I belong / the London I knew is gone?” Time is a burden for anyone who has witnessed where they came of age disappear completely, the lingering conviction that you are still in fundamentally the same place, and the same person despite the transformations, the most profound aspect of this displacement.

With the band generally to the background, and lyrics to the front, there are patches of the first half that make for heavy going, especially for those of us who love Johnson with reservations. In spite of the yearning quality that allows Johnson to rescue ‘I Want To Wake Up With You’ from being pretty much an exercise in repeating the title out aloud, ‘Down By The Frozen River’ veers a little towards parody. At heart pastiche is always empty, especially when it is not clear if pastiche is what is intended, and choosing to do a song in the meta-voice he uses between numbers to josh the audience, is nearly too tongue in cheek to work, Johnson’s delivery coming uncomfortably close to Larkin being sent up by Harry Hill.

The spell is not disturbed for long. ‘Where Do We Go When We Die?’ and ‘Rainy Day In May’ are two of the strongest poetic enquiries Johnson has ever written. In the first, memory is cast as the soul’s rebellion against time, Johnson’s trembling voice asking the question of his elders, being asked the question by a child, and finally asking it of himself, alone and with no one to answer: “Sons become fathers, fathers become sons, as the river flows back into the sea, then so shall we”. For Emerson, “sorrow makes us children again, destroys all differences of intellect. The wisest knows nothing”. Johnson accepts this conclusion and cycle, yet the dignity with which he expresses the hope that even loss is worth bearing, infused with the tentative belief that we may all be reunited in some form again, is more uplifting than certainty ever could be.

Ensoulment closes with ‘Rainy Day In May’, an ultimate pean to meeting and parting. Struck by the knowledge that the face of the person you have just seen could be the story of your life, but that you are never going to test that adumbration because they have got off the train, and you are going the other way, allows Johnson to mourn the many lives we are never going to have. The emotion is as bare as the lyric, its haunting melody supported by his humming, and its upshot of having to live on after the loss of those we love, beautiful and painful to listen to.

In contrast, the second half of the set is a predictably satisfying gallop through the The The songbook. Not that Johnson seems to go any faster himself, his singing relaxed and at ease having got the potentially challenging part of the evening out of the way. ‘This Is The Day’, a song of inspired consequence, is given a blue eyed soul rendition, its hopeful message of how love will forgive you if you fail, and that life is a succession of fresh starts, crowned by the inevitable piano solo that D.C. Collard must, by now, hear in his sleep. The night ends with ‘Giant’, which though neither as coruscating or intense, tribal or ritualistic as some previous renditions, is lovely, with Johnson lending it a gospel feel-good aspect that I had never heard in there before.

The days of Depeche Mode on Wogan, the Stone Roses on Top Of The Pops, and Sonic Youth on The South Bank Show are long behind us, and the relatively quiet critical response to Ensoulment compared to its rapturous reception here in Brixton Academy, does make me wonder whether we weren’t all packed into an echo chamber tonight, another micro community of believers in a world where consensus is impossible, no matter how seriously we take the things we love. Perhaps the world where we all watched the same things and coalesced around the same values was boring and oppressive and needed to go, whereas one that allows a thousand flowers to bloom, even if no one can agree on their value, is progress. And maybe the artist as a great seer is no more than a romantic myth, told by the self-serving to the gullible. Yet as I leave the venue I feel, along with arguably 5000 others, that we have not simply been entertained, but actually understood by the figure on stage, an exchange between an artist and audience that like sincerity, is impervious to improvement or change.