Sometimes it’s nice to sit down

It’s not an opinion often voiced by the under-30s, but festivals are a bit tiring, aren’t they? Especially when, as in the case of Sónar, they take place across two enormous sites and in sweltering Mediterranean heat. The dancing, walking, queuing and careful port-a-loo maneuvering are all well and good, but sometimes it’s nice to take the weight off those feet and engage with the music on a more cerebral level. As luck would have it, we’re afforded an opportunity to do this pretty much as soon as we enter the festival on Thursday afternoon.

One of the most challenging and intriguing artists to emerge from the US noise-into-synth underground, Chris Madak’s performance as Bee Mask was never going to fly on a peak time dancefloor. Nor is it a straightforward ambient bliss-out; his restless, thoughtful music is textural and harmonic worlds away from the Tangerine Dream cliche often ascribed to that scene. Fortunately, an early slot on the SónarHall stage turns out to be the perfect home for it. When we arrive the audience have already taken the collective decision to sit down, and as his exquisitely wrought sonics begin to bounce gently around the room, nobody feels the urge to do otherwise. As we approach a few soaring almost-techno crescendi in the latter half, coloured spotlights begin to gently strafe the crowd. A few metres away from us a couple alternately smooch and take selfies, bathed in a rainbow glow.

For the remainder of the weekend, similar veg-out opportunities are afforded by the SónarComplex stage, a large, seating-room only auditorium, and one of the crowning glories of Sónar By Day’s new(-ish) site. It seems almost trite to mention the air conditioning and deliciously comfy seats, but for Unsound’s Friday afternoon programme in the venue these prove crucial. Oren Ambarchi’s performance of ‘Knots’ with the Sinfonietta Cracovia is an enormous slab of kosmische rapture; during the punishing 10-minute climax, in which Ambarchi and drummer Joe Talia hammer all hell out of their respective instruments, it’s a joy to be able to sit back and let the sound wash ecstatically by. Later, Oneohtrix Point Never and Nate Boyce provide a very different kind of brain food. Whilst Boyce’s bizarre, unresolvable 3D forms wobble and undulate on a giant screen behind, Daniel Lopatin crunches and smears his recorded material into often-surprising new vignettes. There are moments of dynamism and propulsion, but as with his recent R Plus Seven album, they’re matched by passages of uncertain stasis. Sinking slowly into the pleather, it proves easy to take the rough with the smooth. Angus Finlayson

Everything that is solid melts into air

Maybe it’s largely the heat, but wandering around Sónar By Day is an unusual, dislocating experience, especially when one encounters artists who use tangible sounds and samples within their music that feel rooted in the real world, blurring the line between digital and analogue music and the sound of our surroundings. Take Bee Mask’s set on the Thursday afternoon where, amid the darkness and miraculously cool breeze (it must be well over 100 degrees in the sun) of the curtain-lined SónarHall, the lovely sound of water, burbling and blue – oh sweet Heaven, this is washing away my heatstroke – rolls around the room. There are rainforest hisses and clicks, drones and repetition, suggesting Steve Reich soundtracking a nature programme on an as-yet undiscovered planet, a thousand light years away.

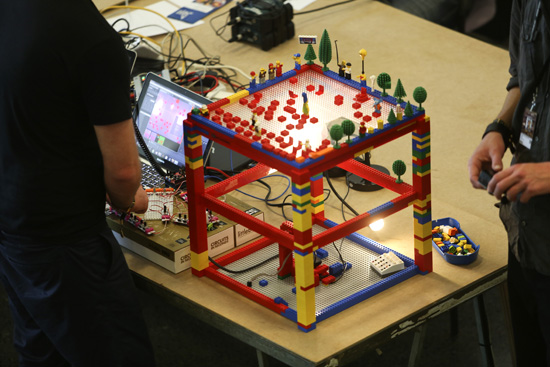

Shortly afterwards, an infernal contraption in the same building starts to rattle and clang away. A framework of wooden beams, wires, scaffolding and the like, it’s all wired up to a large set of speakers, and operated by two earnest-looking chaps in t-shirts. It’s pleasingly ramshackle, the entire structure shaking every time metal is whacked against wood, wood on wood, or wood on wire. It’s as if some shipwrights of the Napoleonic era had formed a proto Test Dept and, after avoiding the attentions of the press gang, had created a rum-fuelled cacophony to celebrate. Matmos’ use of ripping sellotape gives a pleasingly kinky sound, and leaves MC Schmidt struggling to extricate himself from its sticky web before continuing with their set.

Similarly, the intimacy of Jon Hopkins’ album Immunity was physically created using recordings of fireworks, reversing vans and old gear, all forming foundations for its mournful techno. I must admit, I wasn’t quite expecting that this would translate to Hopkins’ set, but this is a revelation. He has the biggest crowd I’ve yet seen in SónarHall, getting either in or out is a nightmare, and the relentless (and yes, still mournful) music is raising the roof. Everything is louder, harsher, bleaker, more booming, while his cinematic forward momentum is enhanced as, in front of giant video screens, Hopkins’ skinny human frame headbangs before a delirious audience. Luke Turner

Todd Terje wins the weekend

I must confess to not having quite wrapped my head around the fresh, limber-fingered funk of Todd Terje’s It’s Album Time yet, but in the context of Friday’s Sonar By Night it matters not a jot. The sensation of entering the festival’s ego-compressingly enormous all-night rave hasn’t diminished since a year ago; you still feel the atmosphere before you’ve even entered the building, and the roar of crowd and soundclash from multiple stages makes the air feel thick and claggy. It’s just as exciting, too; for someone whose formative experiences of dance music hedonism were at massive outdoor British festivals, there’s a familiar thrill to wandering around a space, filled with starry-eyed partygoers, that’s so huge you could quite easy become hopelessly lost within minutes. On the downside, it does mean that we struggle to get close enough to the stage to get the best of Caribou, who sound pleasingly bucolic from a distance, though the still-glorious ‘Sun’ unsurprisingly still comes correct.

It pales in comparison to Terje, though; as he starts we run into a group of friends who’ve just arrived, and his vibrant, plasticky disco funk seems to herald the tip over the edge into party oblivion. It is, of course, ‘Inspector Norse’ that both ends the set and crowns the night – but still more impressive is the way he brings it in, that motif casually emerging from a low-key four-to-the-floor thrum in a manner that’s refreshingly unshowy for a huge space accustomed to far grander gestures. Inevitably, though, it begins rushing to a serotonin-blast climax, everyone’s hugging each other, drinks are spilled or tossed through the air, and then it’s over all too soon, leaving us unable to stop singing and humming that bloody melody for days afterward. Rory Gibb

Matthew Dear – fun. Audion – funner

Matthew Dear may have won reams of plaudits among journalists for his eponymous solo work, but Audion, his harder-edged, more dancefloor-oriented project, is arguably where the real fun is to be had, taking the best bits of modern techno – the gleeful swooshing noises, razor-edge production and bubbling synth lines the milkman could whistle – and sweating out the chugging minimalist boredom, a little like the unchained simplicity of Thomas Bangalter’s brilliant solo work on Trax On Da Rocks all those years ago. On one level there’s nothing clever at all in Audion’s rock-hard, sky-scraping production – yet, as Blawan et al have recently concluded, that makes it actually pretty clever in itself, a trick often much harder to pull off than hiding behind layers of over-intellectualisation.

Audion’s new live show, Subverticul, sees him collaborate with the Vita Motus Design Studio (best known for the ISAM / Amon Tobin shows of 2012) "to mount an audiovisual experience that reconfigures the way live electronic music is presented". In practice, this means Dear plays within a angular structure that looks like one of Rubik’s less successful 80s puzzles, with some really rather gorgeous patterns projected onto it. It’s undeniably pretty, but the spectacle matters not; Dear could be playing within a soggy cardboard box and his gilt-edged beats would still start a party, even in this curiously early Saturday early evening slot at Sónar by Day.

Live, Audion’s music is a great deal more intricate and psychedelic than on record, a glorious mesh of tiny chopped vocal samples, at once familiarly human and disconcertingly alien, thunderously clean techno beats and collapsing synth lines. All surge their way out of the mix like melodic explorers before being submerged in echo and drummed back into submission. The result, it is true, loses something of the devilish simplicity of Audion’s best music, where – as per his best-known track, ‘Mouth To Mouth’ – a simple melodic idea will be allowed free reign over ten plus minutes to devastating effect. But what it loses in lucidity, the music gains in immersive, entrancing feel, at times sounding not a million miles away from the earlier work of James Holden (who, coincidentally, follows Audion with his own live show).

It is, in short, one of the finest live techno shows around in 2014, perfectly weighted between dancefloor and head space, and recommendable to anyone mourning the ballsier, more abrasively noisy side of Daft Punk. And if it may make you rather angry that Dear neglected Audion for so long, then it’s certainly better late than never. Ben Cardew

If it’s a grime state of the nation you want, seek out Butterz

"You don’t have to be part of the nucleus to make it work. Looking for approval from the people that are already there – it’s not really that important," grime DJ and label impresario Elijah told me in an interview last year. It’s a credos he and running mate Skilliam have lived by. Founded in 2010, the pair’s Butterz label has bypassed much of grime’s traditional infrastructure – which, by the late ’00s, was crumbling in any case – instead carving out its own niche in the brave new (online) world.

That act of self-determination has set the label in good stead: it now sits at the top of a growing pile of insurgent grime labels and collectives. When, in a recent Wire interview, Elijah declared "we are the grime scene now", the boast didn’t seem all that bold. But while the Butterz crew have enjoyed plenty of shine as a result of the recent instrumental grime renaissance, they most certainly have their own thing going on, and an afternoon set on the SónarDôme stage turns out to be the perfect place to find out what this thing might be.

Through their own nights at London’s Cable and Fabric clubs, the pair have always aimed to throw a rave first and foremost. MCs are de-emphasised, and the aesthetic leans towards rowdy, party-ready music. It also spans more than simply grime, as Flava D, on warm-up duties this afternoon, demonstrates with an entertaining selection of rebore garage, UK funky and bassline house. (About halfway through her set we begin to tally the number of tracks that contain the word "bass" – it’s matched only by the quantity of Preditah and Champion tags).

Still, it’s once the tempo creeps up towards 140, and Elijah and Skilliam take to the decks, that things get really interesting. The crowd may be just warming up, the soundystem slightly underpowered and the room a tad over-large, but these things don’t seem to matter all that much. The crowd-pleasers come thick and fast, but their forms and origins are sufficiently diverse to avoid the sense of crushing obviousness that often blights victory-lap sets. The recently charting ‘German Whip’ feels like the set’s symbolic peak – what better representation of grime’s recent revival of fortunes? But Butterz’s strength lies in the fact that they don’t just showcase grime’s great and good, nor jealously guard the perimeters of their own aesthetic territory. Instead they revel in the depth and diversity of grime as it stands, over a decade into its lifespan. What’s more, they do it in a way that’s ridiculously fun. Angus Finlayson

Chris & Cosey bring the naughty

It might have been preferable to see Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti play their Carter Tutti re-workings of Chris & Cosey material in the darkened and draped SónarHall venue – this is, after all, nocturnal music, intimate, erotic, intense. As it is, they’re in the Red Bull Dome, which is not a dome but a long cathedral of plastic with light spilling in through the ceiling and rather rattling sound.

Which is no matter this early evening, for as ever Chris and Cosey’s deeply seductive bass manages to creep its way around the room and win over an audience who at first don’t seem too interested. Despite no indulgences, the muggy warmth (the venue is a human humidor) and almost day-bright lighting, I don’t stop moving for the duration of the set. I frequently struggle to find music that represents to me a complete whole, with everything working in the same direction, especially when it comes to gender and sex – you can, I feel, often hear music trying too hard to be male or female and heteronormative, as if gender and sexuality in music were decided by focus group.

What I love about Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti’s music is just how perfectly complete it feels, male and female in union, as well as utterly shifting the power dynamics of most pop in lyrics that, tinged with S&M imagery, treat male and female, domme and sub, queer or otherwise, as entirely fluid. The likes of ‘Driving Blind’ and ‘Love Cuts’ are love songs at heart, made by and about the people onstage in front of us, bringing their audience into the warm embrace of deep bass, Cosey’s trumpet and guitar, and moments that, as my colleague Rory Gibb has said before, suggest these two could knock out out techno 12"s with ease. It’s at once experimental, highly charged, and rather cheeky.

These artfully put together live remixes still sound fresh and current, and arguably few in electronic pop have come close to bringing such eloquent sexuality and romance since the songs were first written in the 80s. They finish with last year’s haunting and hooting ‘Coolicon’ – evidence that, along with the reactivation of Carter Tutti Void, there’s still more magick to come. Luke Turner

That’s real torque

"Check out that wayward snare," mutters Angus in my ear. I’d been too busy falling into a lazy, zoned-out dance to DâM-Funk’s live PA/DJ set to notice, but he’s got a point; somewhere in the mix, among the baked funk licks, a single snare has gone renegade. There it is, restlessly tip-tapping around the groove like an anxious telephone exchange operator, each time falling slightly too short of the core pulse, just enough to snag slightly on the music’s otherwise blissful motion. It’s Saturday afternoon and the effect is low-key rather than heavily affecting, a twist of rhythmic-psychedelic freakishness to complement the heavy-lidded vibe following the festival’s first all-night rave blowout. It’s not long before the atmosphere dips harder and moodier, though; DâM, a charismatic yet faintly confrontational presence behind the decks, stalks to the front of the stage and picks up a keytar, further mangling his music’s otherwise smoothest-ever-smooth groove. Flurries of wildly distorted notes cascade from the instrument in eddies and arcs that recall cocaine-blasted 80s hair-metal and the chiptune freakouts of Cairo’s Islam Chipsy and, at their most extreme, peak with atonal meltdowns that rival straight-up noise music. It’s the ease with which DâM-Funk plays with these contrasts that makes this otherwise languid set so peculiarly intense: the elastic tension between rogue elements within the groove causes his funk to crackle with excess energy, in a way that’s felt on a bodily rather than conscious level. We drift out into the afternoon’s heat-haze even more spaced out than before.

As well as being the auditory equivalent of one of the sugar-boost slushy mojitos they serve at all the festival bars this year, DâM’s set is also a neat insight into one characteristic binding much of the weekend’s most exciting music: torque, that thrillingly visceral lurch you experience when rhythmic vectors audibly twist against one another, compellingly you to radically adjust both mind and body to keep track. Tickling their audience’s audio erogenous zones is Matmos’ stock-in-trade, of course, and Drew Daniel and MC Schmidt’s performance on Friday – an hour-long barrage of sonic, visual and linguistic information – is as fun and quietly radical as ever. "Are you ready for some experimental music?" queries Schmidt of the room as they walk onstage, affecting an excitable sports commentator’s voice, playful glint in his eye. Projected onscreen via a live camera, he sets off an old-style pendulum metronome, creating a tinny tick-tock pulse that in turn activates the sizeable already-sozzled contingent of the crowd. The duo lock in too, following the metronome’s beat to play through the motions of creating dance music. But by design or accident, they soon end up hopelessly off course, wandering in their own free-spirited rhythmic delirium. The audience, confused, gives up their attempts to dance. Yet, there onscreen, stubbornly following its own internal clock, the metronome still swings, forlornly out of sync with the wobbly explorations of its masters. The dissonance is enough to tip my hungover mind into a state of near-collapse.

Late the previous night, at Hessle Audio’s Thursday party at the aptly named (beautifully air conditioned) BeCool club, Kassem Mosse plays one of the best sets I’ve seen of his in years. Gunnar Wendel is best when he’s on quietly contrary form, challenging audience expectations of what role dance music ought to play in a club space while still allowing enough wriggle room for high-charged dancing. Tonight his beats are loose, swung and sultry, forsaking the slow four-to-the-floor he’s often associated with for turbulent motion that’s all hips and elbows. In a dramatic twist, midway through the set he performs a breathtaking sudden de-escalation, dialing down the tempo until kickdrums billow like distant explosions and percussion becomes a drawn-out chorus of shrieks and rattles. He keeps us there for what feels like an age, but it’s impossible to leave; instead, minutes later and almost imperceptibly at first, the pace begins to build, each element grabbing hard onto the others surrounding it and surging forward in a collective shiver of pleasure. Rory Gibb

"It’s just a stone’s throw from EDM, but it’s… it’s a good stone"

It’s not until Saturday night in the same Barcelona club, however, that we’re really put through the rhythmic mangle. Kode9 and fellow label manager Marcus Scott have cause to be proud of what Hyperdub has achieved in the decade of its existence. Indeed, you only need to look back at 2009’s fifth birthday compilation to gain some sense of how significantly they’ve broadened in what’s felt like a very short time, with their tendrils now tracing wider leylines to enclaves of hypersoul, mutant pop and knotted dance music across the globe. It’s more than just a geographical expansion, too, though it’s certainly telling that the label’s three family members on the Sónar bill – Laurel Halo, Jessy Lanza and Inga Copeland – all hail from quite different places. Rather, it’s the feeling of possibility that hits home: the Hyperdub collective have successfully crowbarred open a space where Lanza’s complex synthetic pop and Halo’s cryptic drum vortices can not only exist alongside anarchic bass music mutations from London and Chicago, but can do so in a way that adds additional context, emotional intensity and poise to both.

The label’s four anniversary compilations this year will doubtless go some way towards articulating those connections. But it’s in the dance that they come to life. In BeCool for the Barcelona leg of their tenth birthday celebrations, Cooly G sits on the lip of the stage next to the decks, calmly chain-smoking, gazing impassively outwards into the mounting mayhem on the floor. She’s one-third of the crack team of London selectors assembled for the evening, alongside Ikonika and Scratcha DVA, and her smokelike set mimics the contours of her own productions – frequently skulking in the shadows, offering fleeting glipses of nocturnal urban adventure through ra-ta-tat snares and melodic mist. The night accelerates through Ikonika – pummeling four-to-the-floor spiderwebbing out into Night Slugsian angle-grind bangers and R&B – and Scratcha, whom I initially don’t recognise without his trademark glasses, and in whose hands US rap, UK funky and grime play out a volatile, exciting battle. Dizzee’s ‘Stop Dat’ triggers an energy release from the floor on a par with the previous evening’s Flux Pavilion set in Sónar By Night’s main room, where the EDM figurehead’s jump-up trap and dubstep offered an admirably unsubtle kick to the guts.

Indeed, watching Teklife’s DJ Spinn and Taso wipe the floor with the Hyperdub crowd, I’m again struck by one of the predominant feelings I experienced at last year’s Sónar – that, for all the attempts made by fans and the supposedly credible ends of the music press to distance the EDM phenomenon from so-called ‘underground’ dance music at large, musically the divides are a hell of a lot narrower than many might have you believe. Spinn and Taso’s set is a thrilling tornado of reference points, drawing broadly for sample matter: soul samples, hip hop brags and chants in tribute to the late DJ Rashad collide with footworking percussion, raw synthlines and warping trap sub-bass. While more deeply rooted in atmosphere and intent, it’s frequently as omnivorous in its search for dancefloor firepower as the crassest of big-room EDM – a reminder that the ostensible rift between the two is often less due to some underlying aesthetic difference than to economics and cultural sensitivity (or total lack thereof). That the Teklife crew have the potential to make ripples around the globe is exciting. You imagine that the inbuilt community solidarity between its members might offer some grounding ballast against the depersonalising, uprooting tug of capital in the higher economic echelons of the global dance industry. Rory Gibb

"Let me see your footwork, baby…"

The evening’s reddish sunlight casts a warm glow across the SonarVillage complex, and DJ Harvey looks every inch the greasy bad cop his track selections would have you believe: lubed-up acid house and slippery cosmic disco, mixed with such careful weighting that the joins are seamless, all the pieces interlocking. The packed dancefloor on the astroturf in front of the stage can doubtless feel like a scrum when you’re caught in its midst, but from a distance its sea of bodies in motion acquires an oddly weightless grace. Individual dancers reacting to the actions of those around them take part in an intricate game of feint and parry with their neighbours. One particularly hammered raver loses their footing and a circle of space suddenly opens around them. Elsewhere, a group of British guys in sunglasses throw comedy gun-fingers into the air. At population level what emerges from these simple interactions are lovely, dynamic patterns: eddies and flow channels emerge and dissipate, densities shift, abrupt shifts in the music’s energy send out visible shockwaves as people adapt their style of movement. When it comes to club culture, watching large groups of people dance – spotting subtle interpersonal interactions, knowing smiles, mimicked moves, even flashes of confrontation when someone oversteps the mark – is one of life’s pleasures.

Rewind to the previous evening, same place, same time, and Theo Parrish is presiding over affairs with an affable air to fit the occasion. It’s his voice urgently whispering from the speakers, too: "Let me see your footwork, baby…" Set amid a sidewinding whorl of snares and jazz chords, it’s the vocal calling-card of one of his best Sound Signature 12"s in ages, ‘Footwork’, and feels like half-taunt, half-invitation, its bass blasts throwing down the dancefloor gauntlet. In the context it also carries a bittersweet pang; this is the first Sonar since the death of footwork pioneer DJ Rashad in April, and plenty of the music here is steeped in his influence. Parrish was born and raised in footwork’s home city of Chicago, and while the connection isn’t made explicit, at this moment the song feels like a (perhaps unwitting) nod to Rashad’s work and legacy.

The sensation recurs at the Hyperdub party, when Kode9 draws heavily for Rashad’s music in a set that’s the most exciting yet moving of the weekend. I discussed earlier the pleasures of rhythmic disorientation; in footwork, the torque between multiple conflicting rhythms underlies not only the music’s kinetic charge, but also its emotional impact. Kode’s set is pure adrenal joy to dance to – that much is immediately clear when I spot the Quietus’ former footwork sceptic Luke Turner flailing wildly around down at the front. But many moments also pack a gutwrenching punch. The Gil Scott Heron sampling ‘I’m Gone’ whirls together intense sadness and piledriving energy until it’s impossible to distinguish the two. And ‘Ghost’, already one of Rashad’s finest beats, carries an eerie charge now. That moment, when its translucent soul sample trickles through the mix to wrestle control away from the drum machine, stuns the floor dead in its tracks, and sends goosebumps shredding up my spine. Rory Gibb

Context is everything

It’s such an obvious point as to hardly need stating, but a festival is as much about times, places and levels of inebriation as it is about music. It might be pissing with rain, painfully overcrowded, too early or too late; the lager may give off an unpleasant eggy odour, the onsite catering leave much to be desired, the party dust prove mythically difficult to obtain. Many things can turn perfectly good performances into dreary lipservices to hedonism. Equally, however, when everything comes together, a well-placed set can cast music you know well in a surprising new light, or offer a captivating introduction to music you don’t.

Nisennenmondai certainly fall into the latter camp. There’s practically nothing to the Japanese trio’s sound: just parched swells of guitar noise, cadaverous basslines and Sayaka Himeno’s brain-boringly motorik drumming. But entering the darkened SónarHall stage a few minutes into their early evening set, the sparse intensity of it exerts a black hole-like pull on the crowd. I’d not seen the band before; one imagines that in usual circumstances their brand of pared-back kosmische might function as a particularly forbidding headtrip, or else serve as music for beardy types to nod robustly to at an early doors weekday gig. In the context of Sónar, however – nestled amongst the dancefloor luminaries and the producerly avant-garde – this is techno distilled, a relentless four-four epic with the skeletal precision of mnml but the grit and drama of human exertion. As if to compound the techno comparison, each new hi-hat pattern and dead-eyed snare roll elicits cheers of euphoria from the crowd. The only regret is that the whole thing didn’t happen about eight hours later.

The following day, Jessy Lanza’s music undergoes an almost inverse transformation. Those who have reached ententes with their hangovers in time for her mid-afternoon set are faced with merciless 30 degree heat; many of us crowded into the sliver of shade at the lip of the SónarVillage stage. On record, the Ontario’s native’s music is pretty wintry in character, but if she’s at risk of melting in the heat then Lanza doesn’t show it. Instead, the subtle warmth and playfulness of her music rises to the surface. It’s hard to think of a better way to ease into a long, hot day.

Of course, there are those who fare less well too – particularly when confronted with the vast recesses of Sónar By Night. SónarCar is the smallest of the venue’s stages, and home to some of the night festival’s most outre programming. A modest area nestled at the far end of one room, there’s a strange sense of a space-within-a-space to it – almost as if it were a 300 capacity venue floating in the immense blackness of space. Not the most reassuring setting, then; certainly not for Copeland, whose sepulchral dancefloor pop seems destined to lurk in the shadows at the best of times. It’s hard to imagine what the ex-Hype Williams producer must think of the event she’s been booked at (around the same time as her Friday night performance, Flux Pavilion is pummeling a few thousand revellers into submission next door). Wreathed in dry ice, making the minimum of gestures and disappearing mutely backstage before the end of her last track, Copeland’s response seems to be the same as ever: a graceful retreat into anonymity. Angus Finlayson

There’s a lot more to Sónar than raving

Sónar, lest we forget, is not just a music festival: it is an ‘International Festival of Advanced Music and New Media Art’. A little long-winded? Maybe. But it is a title Sónar lives up to, thanks to hundreds of fascinating nooks and crannies at Sónar+D, the festival’s playground of new technology and talks, which takes place as part of Sónar by Day.

The wealth of activity is almost dizzying: within half an hour of arriving on the Thursday afternoon I’ve taken in a masterclass on new trends in wearable devices, skimmed a discussion on brands and music and heard, briefly, why gaming is a safe bet for investors (in Catalan). I narrowly miss a round table on "Women hackers: cyberfeminism, hacktivism, open culture and free tech education" as I want to catch Flava D, a clash that is unlikely to be repeated at the Reading and Leeds festivals this summer.

Best of all, though, is the MarketLab, billed as "a selection of the most outstanding projects by creative laboratories, universities and companies", and a hands-on technological playground that makes your new iPad look decidedly 2012. Take, for example, the work of the Kunstuniversität Linz, who have brought along edible synthesisers, sound graffiti, noisy jelly circuits and musical oranges, which you squeeze to make both noise and a delicious glass of juice. Or how about the Berklee Technology Innovation Lab’s Orbit Suit, which seeks to free musicians from their laptops with the use of four Numark Orbit wireless controllers attached to a Tron-esque suit?

Get bored of these and there’s always the AppCafé – where you can play around on tablets loaded with a selected range of the latest apps and try out an Oculus Rift headset – as well as numerous art installations, product demonstrations and audiovisual performances. Throw in a handful of particularly refreshed Sónar punters milling around in wonder and you have a recipe for an entertaining afternoon.

Sónar+D, it is true, probably remains a peripheral concern for most of the people who attend the festival. But the fusion of music, technology and art that it offers is a reminder of how different Sónar can be, a nonconformity that is highly welcome in these days of identikit boutique festivals and corporate concert boredom. Ben Cardew

Richie Hawtin’s throbbing column offers visual intrigue, but little else

Communions between Richie Hawtin and the art world have a certain grim inevitability to them, given the White Cube character of much of the mnml behemoth’s endeavours. The latest, a revival of his Plastikman alias with the subtitle ‘Objekt’ (no, not that one), was first commissioned for New York’s Guggenheim museum, and it’s marketed as a "concept" rather than a live show per se. Presented here as the climax of Thursday’s By Day program, it turns out to be more puzzling than it is enjoyable – and it isn’t very much of either.

Its centrepiece is a huge incandescent pillar (or "obelisk") across which luridly coloured digital graphics throb and whirl in time to the music. It’s tempting to think of this as a mega-budget satire of the return of DJ-superstar culture. After all, what better way to critique macho EDM blow-outs than to have your crowd stand around, hardly dancing, gazing in awe at a giant phallus? Sadly it seems unreasonable to ascribe Hawtin with this level of self-awareness; his intention is likely much more baldly sensory. And while the obelisk would probably be pretty good cop on drugs, the music accompanying it – staid machine techno, vaguely nodding to the original Plastikman sound but with little of its energy, dynamism or intention – would not.

The following night, our man reappears on By Night’s SónarClub stage under his own name for yet another novel performance. ‘Close’ (no, not that one) purports to "give full transparency to the improvisation and technological manipulation" behind Hawtin’s performances; qualities that "set him apart from the traditional definition of a DJ". It’s difficult to discern how exactly this manifests in the performance; after all, video feeds and revealing lighting are pretty much par for the course in big-room DJ sets these days. Conceit aside, Hawtin’s set is reassuringly familiar from the last time I saw him, at Sónar 2012. It’s nice, I suppose, to have some constants in life. See you in a couple of years, Richie. Angus Finlayson

Massive Attack are suitable Sónar headliners but leave questions unanswered

As an arty dance music festival, Sónar has it hard when it comes to choosing headliners. EDM may be a grunting global behemoth, but the identikit housealikes of David Guetta, Avicii et al don’t exactly fit into the Sónar blueprint of progressive music. Skrillex, who played last year, proved very popular, particularly with locals, but left some people indignant at the very idea of his booking. That leaves a dwindling pile of "classic" (for want of a better word) dance music groups for organisers to choose from, and in general they’ve done well, with New Order, Pet Shop Boys and Kraftwerk all proving excellent value for money over the last three years.

Massive Attack, who headline this year, seem a little more risky: they’re dance music only in the widest sense of "not rock" and their mix of hip hop beats, reggae sensibilities and paranoia is a little laid-back for a Saturday night headliner. In the end, though, they triumph. Their powerfully gloomy show may not exactly be a party starter, but ‘Risingson’, ‘Teardrop’ and ‘Angel’ are greeted like returning heroes by the crowd. So why, then, do I feel slightly underwhelmed as they bash away at ‘Unfinished Sympathy’ amid general hysteria?

Because, somehow, it doesn’t feel like their song. Sónar, of course, is no place for rockist feelings of live authenticity, but it’s hard to shake the feeling that what we’re watching is a band of (very professional) session musicians recreate a song made 24 years ago by a group of people who are largely absent today. Of the song’s five writers only two – 3D and Daddy G – remain within Massive Attack, and it’s not really clear what they do within the live set-up beyond providing occasional vocals. 3D has a bank of electronic equipment he pokes away at, but it’s hard to judge its effect on the overall sound.

Should this matter? No. In fact, you could argue that Massive Attack’s loose, sound system collective roots make a nonsense of this kind of complaint. Does it matter? Maybe a little, as I’m transported back to the Massive Attack gigs of the mid-90s where Mushroom would sit forlornly behind the decks, occasionally hitting a tambourine and wondering what he was doing there. He soon departed.

You could argue the whole issue is irrelevant, the debate over laptop live performance versus guitars entirely played out. But Sónar, perhaps more than any other festival in the world, shows new ways that live electronic music can progress, featuring both innovative live shows (Plastikman’s EX spectacle, James Holden’s electronic jazz) and demonstrations of new musical technology where music can be made by squeezing an orange or wiggling your eyebrows (see above). To be headlined, then, by a band that adds waddling guitar freak outs to the sublimely sample-based ‘Safe From Harm’ is maybe a little disappointing. Not that the audience care. Ben Cardew