It’s long past midnight on a Saturday evening in Riga, Latvia, and HARPY are delivering a cleansing post-industrial ritual, an electro-crust punk sound bath which shocks synapses into hyper acuity rather than tranquility. The Providence, Rhode Island-based duo, Gyna Bootleg and Pippi Zornoza, begin their set with a yearning drone which evokes a broken synth impersonating a hurdy gurdy before a scream emerges from the void and sends a spasm through my core. From there the frenzy keeps building, bass hits with such intensity it could collapse the scaffolding holding together your sense of self. Noise comes in waves equal parts unnerving and totally ecstatic.

I actually piece together the visual aspect of the duo’s performance together from Instagram reels after the fact. That’s because they forego the raised stage to play on floor, the pair and their electronics encircled by the crowd. On tiptoes, three or four rows back from the centre, I only catch the barest glimpses of Bootleg and Zornoza, flickers of a screaming face or a raised arm occasionally coming into view. But you can chart their performance’s vicious presence through ripples in the crowd, the circle stretching and reshaping itself like a shoal of fish beset by a marauding shark. To be clear, this isn’t a criticism or complaint: you really don’t need to be able to actually see HARPY to get the message, their sound and how it effects the crowd around you is more than powerful enough on its own. They’re a twin-headed sonic battering ram, a scratch of fiery catharsis. When they scream the chorus to ‘You Don’t Know Shit’ from 2022’s A Sacrifice, you feel for a moment that any oppressive apparatus turning the world sour is about to collapse under the sheer ferocity of what they’re doing.

HARPY are the penultimate act on the final night of the 2025’s edition of Riga’s Skaņu Mežs (the name translates to Sound Forest), and their joyous noise encapsulates what makes the festival so spectacular. Skaņu Mežs 2025’s greatest triumph is its celebration of unconventional sounds’ ability to upend more than just your ears. So many of the sets across the weekend use vastly different means to spin you around, turn your mind inside out and spit you out in such a way that the world doesn’t quite look or sound the same afterwards. The sheer diversity and quantity of stimuli Skaņu Mežs expose attendees to over a couple of evenings can be overwhelming. But the way the festival condenses these sounds and images so close together is also its unique strength, offering a compelling sense by the end that your brain has been rewired.

While Skaņu Mežs is preceded by a week of smaller concerts and a brilliant programme of lectures, talks and masterclasses from artists playing, the main bulk of the festival takes place across two nights at Hanzas Perons, a former cargo warehouse converted into a permanent concert hall. Across those two days is a lineup which crosses generations and disciplines, from free-improvisation into radical electronics, gleefully disorientating DJ sets, hip hop and heavy rock. But it’s not just eclecticism for the sake of eclecticism – there are threads and throughlines. The curation plotting a trip through radical music that’s zig-zagging and discursive rather than fixed and linear.

The diversity of sounds is matched and amplified by how the organisers use the venue, treating a fixed location as an opportunity rather than a hinderance. Hanzas Perons is expanded from a music venue into a multimedia happening, video installations from Richie Culver (who isn’t playing at the festival), and Pierce Warnecke and Matthew Biederman (who are playing at the festival) are on loop throughout outside the main hall. An art exhibition of hypothetical album covers by Margrieta Griestiņa decorates the bar area. Festivals are most vital when they offer an interruption of the mundane, and that’s something Skaņu Mežs lean into as they immerse attendees in a space of radical sound and vision, a world of deviant and defiant art. It’s a weekend of stunning performances, but these seven highlights capture the depth and breadth of Skaņu Mežs 2025.

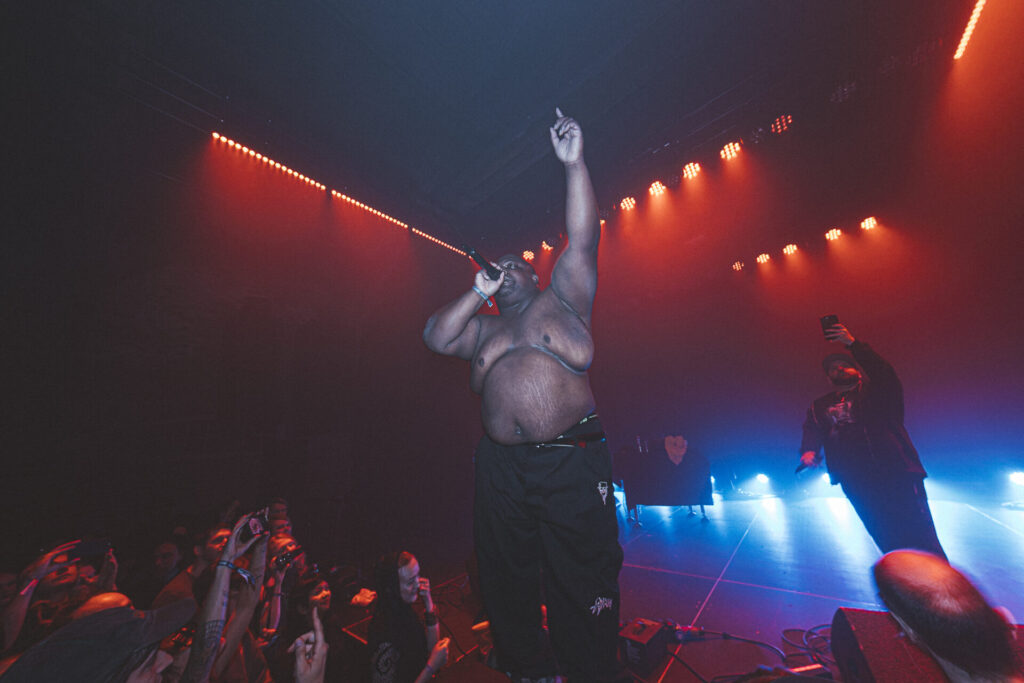

Fatboi Sharif

Fatboi Sharif’s recordings conjure a spooked-out delirium. Lyrics rooted in horror and sci-fi imagery create elaborate narratives over beats that lurk and stalk. On the surface there’s an affinity to horrorcore in his tracks, but Sharif goes deeper into the supernatural and the eerie, using them as starting points to grapple with themes beyond creepy fantasies. His rhymes are laden with rich, complex storytelling. The giant catfish, devils, crows and burning cities populating his songs acting not just as fantastic figures, but intricate allegorical and narrative devices. While his records have a macabre and claustrophobic edge, his live performance, backed by DJ Boogaveli, brings out a gleeful, celebratory energy residing in the music. ‘Static Vision’s’ coda of “I ain’t scared no more” becomes infinitely more triumphant and rabble rousing when belted out live, ‘Battlestar Galactica’ sucks the whole room into its infectious bounce. The pair are relentless showmen, hyping the crowd, climbing into the audience, showing that while the music is brooding, it’s also full of joy. This isn’t to say the intensity of Sharif’s records is diluted or compromised live, rather, the duality in them becomes clearer – this music confronts nightmares instead of succumbing to them.

R3YWYA

R3YWYA is Riga-based sound artist Evija Ābrama. Live, her music, crafted from a table of electronics, exists as a disorientating paradox. Fierce and intricate, sinister and pounding, static and constantly reformatting. It’s monolithic, but as your ears focus they start to be drawn to layers of scramble and fluctuation. Her whole performance is a meticulously crafted exploration of sound’s ability to viscerally alter our connection to our surroundings. A perplexing effect best brought home by the fact that during her set some people start dancing at the front while others seem to be sucked into their chairs. Opening in a deluge of squelching, babbling, charred torsion from her electronics, incessant stabs of synth lay a fixed pulse against music which sounds like it’s in a constant state of explosion. Midway through, she assembles a prolonged vortex, a sheet metal wall of noise which also contains one of the most disconcertingly body-activating moments of the festival – a swarm of bass frequency underneath congealing into a flickering beat which might be an aural hallucination but has a somatic impact that’s undeniably tangible. Towards the end, tones that sound like error warnings start to have the effect of sonorous drones. It brings home just how comprehensively her electronics rewire the sense of space and place. Pummelling and vibrant all at once, the vast hall of Hanzas Perons seems to get engulfed and then abruptly compressed by her set.

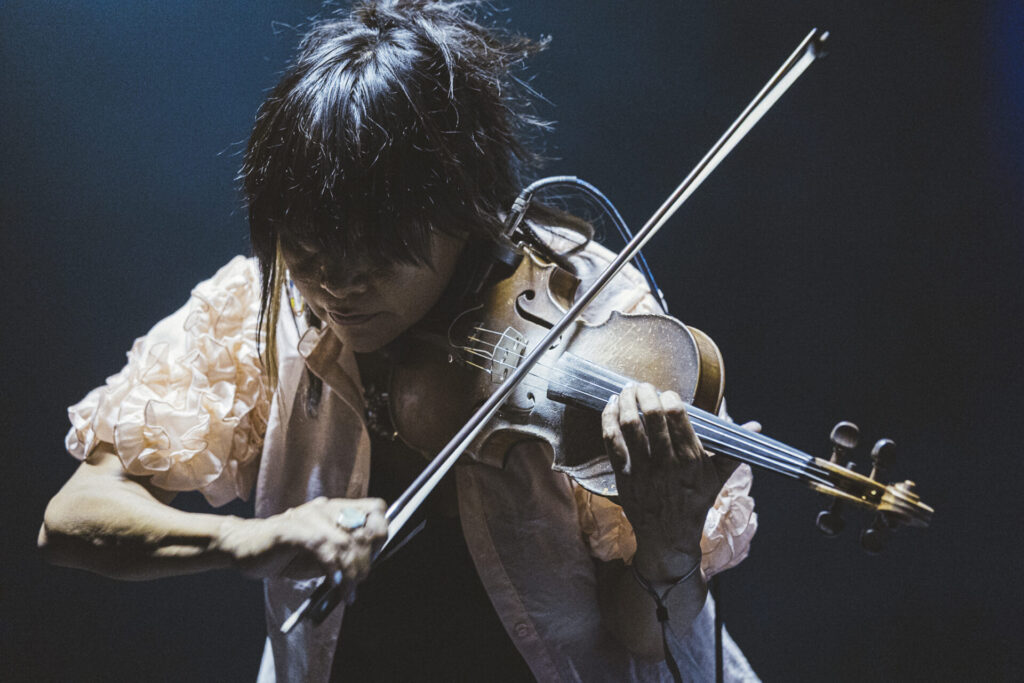

Laura Ortman

It’s a sign of the consideration that goes into curating and sequencing Skaņu Mežs that Laura Ortman plays immediately before a blistering set by British saxophonist John Butcher. Butcher has played a key role in extending the language of the saxophone, using it as a tool to control feedback, turning it into a percussive instrument and exploring the lyrical possibility in circular breathing (all of which are explored in his solo performance). Similarly, New York-based Ortman is stretching the possibilities of the violin, hooking it up to an array of effects and feeding it through a guitar amplifier. She begins with a gentle, focused exploration of the instrument’s body, tapping, scraping and squeaking curiously verdant concrete tapestries from it. From there, she puts bow to strings and unleashes an ecstatic blast of sound, moving from soaring ascents into walls of distorted shred. At points the instrument sounds like a droning horn before the furrowed contours of the violin comes screaming back. At others, she fires its signal through arpeggios and modulation effects, extending the violin out into a complex electro-acoustic hybrid. It’s a scintillating set propelled by an instinctive livewire energy and an expert grasp of the violin. A reminder that new possibilities can still be found when old instruments come into contact with the present. Like Butcher, it’s a thrilling demonstration of an artist diving deep into their instrument and stretching the limits of what it can say.

Pierce Warnecke and Matthew Biederman

Sound artist Pierce Warnecke and visual artist Matthew Biederman’s set builds from Phytomorphic Topographies, an audio-visual collaboration assembled from a week recording sound and video in forests, bogs and nature reserves in central Latvia. One iteration of the work is in situ as an installation in the main hallway of Hanzas Perons throughout the festival, while their live set builds from the same material. As they explain in a talk the day before, the project involves a unique intersection between nature and technology. Warnecke field recorded with a variety of different mics, from hydrophones and geophones to more panoramic devices to get multiple perspectives on the soundscape, these recordings then treated, processed and effected. Biederman’s footage was fed into AI mapping software to create surreal, impressionistic topographies. Linking it together, light from the video element is also connected to and affects the audio. Live, their work paints a natural landscape that is anything but passive and tranquil. Audio zooms in and out, pulling out subterranean bass and disturbingly up-close buzzes and rustles. At points, Warnecke uses his Ableton controller more percussively, playing samples of natural sounds that have been rendered alarmingly martial. Elsewhere, a loon’s call is fed through granular delays, warping into alien cries. The visuals constantly spin and bend, strange eddies and currents of light ripping through them so what starts pastoral ends up increasingly mangled. Their performance captures both nature’s precarity and its intensity, ecosystems as constant flux, contested sites between actors internal and external. Towards the end, a crackling sound enters which could either be something rustling in the trees or the speakers buckling under the immense frequency Warnecke’s extracting. A confounding moment which sums up the loaded poetics and ferocious discombobulation encased in their approach to field recording.

Shabaka Hutchings and Hamid Drake

A few minutes into Shabaka Hutchings and Hamid Drake’s set the pair hit a series of abrupt pauses, halting in momentary chasms of silence before restarting. They’re like inhalations of breath, as if the pair are slowly modulating our breathing to prepare us for the flow of sound they’re about to immerse us in. These fiendishly tight pauses also establish a seemingly telekinetic connection between the two, Hutchings, a London-based composer who leads Shabaka and The Ancestors and is a former member of the Comet Is Coming and Sons Of Kemet, and Drake, a veteran percussionist who’s played with everyone from Don Cherry to Herbie Hancock, have an instantaneous familiarity. Once that connection is tuned in, they enter a gorgeous flow state, one which has a surprisingly prominent amount of saxophone in it considering Hutchings’ recent focus on flutes. Here, he alternates between sax, a wide selection of flutes and onto shimmering electronics, situating the music on the line bridging Alice Coltrane to Pharoah Sanders (who Drake collaborated with) while deftly bypassing the cloying new age excesses artists working in that space can risk falling into. Drake’s drumming has the force and fluctuation of a waterfall, relentlessly tethered to the gravity of a groove but twisting and bending his playing to turn rhythms on their head. There’s a liquid instability, at points he drops abrupt changes of pace while never losing the forward flowing momentum, tempo changes arriving like bends in a river the music flows around. At the start most of the audience are sat on chairs or lying on the floor. By the end, when Drake moves to the front of the stage, playing a single drum and singing, a crowd is dancing, the floating quality of their music filtering into the audience and levitating the room.

Joan La Barbara

Alongside a rich and varied practice performing and composing her own music, Joan La Barbara has worked with a dazzling array of minimal and experimental composers – Morton Feldman, Robert Ashley, Steve Reich and Philip Glass. She’s a vital voice in the history of exploratory music, one you may have heard even if you’re unfamiliar with the name. Her solo work is rooted in an exploration of the human voice, entangling beautiful melodic phrases with more abstract extended vocal techniques. Her performance at Skanu Mezs, part of a number of dates around Europe, is especially welcome for its focus on her own compositions. While other vocalists pushing the limits of the human voice through extended technique, such as Audrey Chen or Ute Wassermann, often operate in freewheeling, instinctive, improvisational settings, La Barbara deploys similar techniques in more composed, elegant spaces. Throughout the set she performs to backing tracks, threading her voice into intricate tapestries of ululations, chitters, and shivering held tones. A rendition of ‘Erin’, a composition by La Barbara which Jóhann Jóhannsson turned into ‘Heptapod B’ for The Arrival soundtrack, brings home the rich, extra-terrestrial slant in her music. She closes with ‘Windows’ a lengthy piece from an opera which she has yet to finish. In its gentle ascents and lulls, occasionally accompanied by the creaks and whines of a string instrument and trickling water, we hear the full expressive possibilities of the voice when it’s allowed to wander beyond the confines of conventional song and language.

Pamirt

Latvian quintet Pamirt (the name roughly translates to ‘dying out’) play a set of theatric, doomy, gothic-tinted nocturnes. They open with vocalist Kristiāna Kārkliņa delivering a haunted, harrowed performance with her voice and piano before guitars and drums crash in and catapult everything into a wall of thick distorted riffs. They stay in this precarious sway between pounding heaviness and feverish songcraft. Beats alternate between acoustic and electronic, guitars move from chugging to swarms of spooky textures. More than just abrupt switches in dynamic, there’s an epic sense of unease seeping through their songs. It feels tied to the rural Latvian landscape – their instrumental passages evoking a wintry, overnight inter-city coach ride through thick forests and fields rendered luminous in the dark through blankets of thick white snow. A kind of darkly esoteric interpretation of heavy music which latches into the expressive possibility in riffs and pounding drums beyond brute force. On paper, having a band so rooted in dramatic, ominously romantic songs and heavy rock structures seems an outlier on Skaņu Mežs lineup. In practice it makes perfect sense. The form they’re working in might be familiar, but they test the limits of what their instruments and song forms can conjure.