Semibreve is haunted. If there’s a leitmotif running through 2024’s edition of the festival in the historic city of Braga, Portugal, it’s music which delves deep into the spooky possibilities of sound. This isn’t to suggest the late-October festival is somehow Halloween-themed. The moods and effects moving through the sets mark an embrace of something more subtle and profound than pumpkins, ghosts and Hollywood horror cliches. Neither is it a return to the currently widely revisited aesthetics of hauntology. Semibreve 2024 isn’t about imaginary pasts spawning unrealised futures, but rather sound as membrane through which omens leak forwards and backwards into the present.

The artists playing here frequently embrace the spectral, in both the sonic and supernatural sense of the word. Spectralism refers to a compositional approach which embraces sound as physical material, concentrating on timbre, tone and texture over harmony. Diving deep into overtones and exploring the miniscule internal aspects of music, spectralist compositions can often descend into complex musical theory. For many of the performances at Semibreve, however, these timbral explorations feel more instinctive and nuanced, based on responses to the emotional weight of slight shifts in tone and timbre. Which is to say, from Kalia Vandever’s tender trombone through to Kevin Richard Martin’s immense noir dub, there’s an unusually large amount of disarmingly beautiful sonics at Semibreve 2024.

Tied into this as an exploration of music’s ghostliness. Its knack of dallying with spectres. It’s ability to dredge up the past, to carry residues from other times and spaces, to be a portent of what might be on the horizon. To seep through a room, possess a space and make it feel something other than what it is. Music as the magical original augmenter of reality.

All of these combine in a sound installation by Jim O’Rourke, which diffuses through Casa Rolão for the duration of the festival. Casa Rolão is an unusual building, a merchant’s house built in 1761 that seems to have undergone several facelifts in the intervening centuries without fully discarding its original framework. Stone staircases lead to rooms with plastered walls and timber beams wonkily holding up ceilings. O’Rourke’s 30-plus minute ‘The Stone Tape’ loops through a small room in the building. On Saturday morning, I find myself completely absorbed in its uneven churn of chiming metals and fragmented orchestrations for far longer than a single iteration of the piece. For an installation, it’s remarkably dynamic. There are crescendos and diminunendos as sighing metals emerging alongside distant voices. It evokes an odd space, a sort of pastoral noir. Played in a room which, although historic, also feels domestic, the installation takes on an apparitional quality.

The tempos and settings of Semibreve are perfectly suited to a considered exploration of sound’s evocative potential, its possibility to be a vehicle of deep inner and outer reflection. To shift how we interact with a place and ourselves. The festival is spread over four days, three of which centre around performances at Teatro Circo, a gorgeous, ornate theatre in the heart of the city. it was built in the twentieth century but feels like it comes from a time much older. Elsewhere, Semibreve takes in performances at a series of spectacular churches, and gnration, which has two rooms hosting the more club focused side of the programme. During the day, artists performing at the festival host panels and lectures, while in situ sound and visual installations are also spread around the city.

One of the lectures, by Portuguese researcher, curator and artist Margarida Mendes, touches on themes which resonate throughout the festival. Her talk, ‘Expanded River Listening’, provides a rich overview of her work travelling along the Mississippi, researching traces of the industrial and natural flux of the river. Mendes’ work goes deep into the full weight and depth of place, and the river as a conduit for sound. We hear of a waterway drastically affected by pollution and climate change, political decisions and the people who live by it. Listening is the fulcrum of her research. As she explains, she’s interested in the longue durée of sound, for instance how our sensory mechanisms change due to industrial noise, and how sounds mark an ecosystem. She mentions that an approaching oil tanker is audible underwater 24 hours before it appears on the horizon. She later plays aquatic field recordings, a bubbly soundscape dominated by an eerie electrical presence. Mendes shows sound is both portent and trace, layered in complex meaning.

But of course, Semibreve is a diverse festival. And it captures more than one aspect of sound’s power. The Friday and Saturday night witness high energy, celebratory DJ sets from Nídia, Saya and Ziúr. While working with quite drastically different record collections, they’re connected by a powerful awareness of sound as a force of agitation and activation. A spirit capable of possessing the body and making it move to a new rhythm. These three sets are among Semibreve’s most ecstatic, triumphant moments. Where sound is displayed in its full, visceral potential. They’re impossible to really put into words. You just had to be there in the room to really sense it. They were the perfect release from the more intense, contemplative highlights picked below.

Kalia Vandever

Kalia Vandever’s festival-opening set conjures friendly spirits and benevolent ghosts. Largely built on pieces from her 2024 album We Fell In Turn, as she explains during the set, much of the music she’s playing comes from a period when she was reconnecting with her childhood while also taking inspiration from the deep spiritualism and ancestral awareness of her Hawaiian heritage. This manifests in delicate, slowly unfurling melodies played on warmly toned trombone and sparse electronics. Later, Vandever sings in tender, undulating chants. Subtly toying with the quirks of the trombone, she brings forth eddies of colour and fluctuation, conjuring mental images of mist and fog, quivering smoke and fading embers. The warm haze of recollection, of something diffuse yet undeniably present, resides in the very form of the pieces she plays. It feels intimately tied to the opacity of memory, the way minor events often leave the biggest traces. Simple in components yet profound in effect, she has a rare knack for crafting music which is quiet and subtle yet moving and consuming. Vandever performs in the spectacular Basilica do Bom Jesus do Monte, an ornate church atop a mountain overlooking the city. A storm is raging outside. But all that disappears as Vandever douses the space in the warm glow of a friendly haunting.

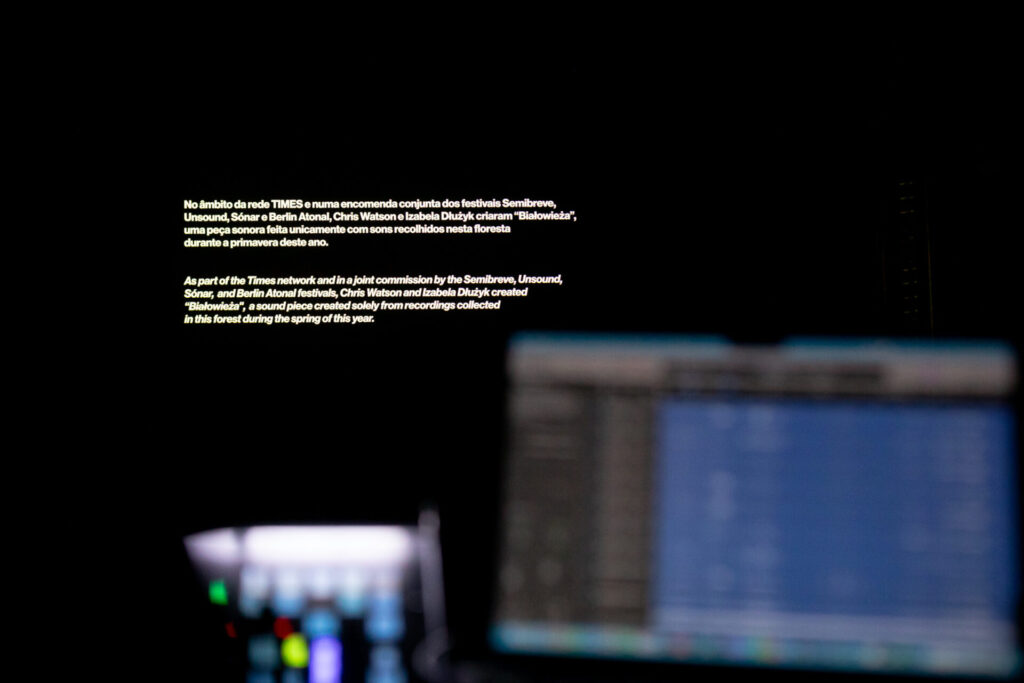

Chris Watson and Izabela Dłużyk

Chris Watson and Izabela Dłużyk’s Białowieża takes its name from a forest on the border of Belarus and Poland. Białowieża’s roots are primeval, and it’s described in the Semibreve festival programme as one of the last remaining examples of “Europe’s pristine and unspoilt natural landscape”. In the last century environmental decline has taken its toll, while in more recent years it’s been a passage for refugees from the Middle East and Africa seeking sanctuary in the European Union. Watson and Dłużyk’’s composition, diffused in complete darkness through the ornate confines of the Teatro Circo, is created from field recordings the pair made in the forest. Indeed, Bialowieza is a composition of nothing but field recordings – no instrumentation has been added, there’s no noticeable manipulation of the sound. Despite the prevalence of field recordings and natural sounds in contemporary music, it’s actually rare to hear them presented so nakedly, and so loudly. It has a powerful effect. Bialowieza is immersive, but it’s often also an uncomfortable, disquieting experience. There are intriguing details and events to be heard, it’s lush and verdant, but the cumulative effect, for me at least, is a sense of staring into a fructus void. A diverse array of birdsong is the most persistent element, but here it’s neither peaceful nor tranquil. There’s also a marked lack of human sounds, with no passing traffic or airplanes to be heard, until (spoiler alert) about three quarters of the way through a trace of humanity emerges briefly but violently. It is a remarkably bold, ambiguous work of art. Field recording as provocation, perhaps. Moving between cacophony and strange serenity, croaking interruptions and alien sounding bird calls, we’re confronted with the full intensity, precarity and noise of an ecosystem. A haunting across space rather than time as an imperiled soundscape in Poland suddenly lands in an inner-city Portuguese theatre. And we’re left to make of that what we will.

PYUR

PYUR explodes club music and builds something vibrant from the wreckage. Her Friday night set is based on material from Lucid Anarchy, her album released earlier this year. That record came from a period of displacement, PYUR, aka Sophie Schnell, living across different countries in Europe. Live, it sounds like the ghosts of rave being fired back out onto the dance floor. Which is to say, while a lot of music which rewires rave aesthetics feels aimed at heady contemplation, PYUR’s also achieves bodily activation. Drums pound as though they’re arriving onto the dancefloor through an interdimensional threshold. Trancey synth seem to shatter as they make contact with the soundsystem. At points, shards of a track are suspended in the air, as if she’s slowed down an explosion and started playing with the fragments. Elsewhere, broken loops are given disturbing prominence in the mix, haunted background textures taking ominous presence. She wields a brilliant balance of pace and energy. Many of the sounds she uses are abstract, the rhythms are intimately destabilised. But through the complex tessellations a swaying motion moves out from the stage and into the audience.

Iceboy Violet and Nueen

Saturday night’s set by Iceboy Violet and Spanish producer Nueen focuses on their album from this year, You Said You’d Hold My Hand Through The Fire. In the dark confines of gnration’s Black Box venue, Iceboy Violet performs the whole set from the crowd, striding through the circle built up by the audience, gently leaning into members in the front row as if searching for a shoulder to cry on, or as their despair peaks, laying virtually motionless on the floor. The whole set tracks the harrowed self-reflection and fraught recollection that strikes post-breakup. A visceral sense of being haunted by the past and building up the courage to halt its possession of the present. Nueen’s tracks are perfect for the music’s troubled catharsis. While propulsive, and carried upon huge thudding kicks, there’s also a sense they’re dissolving between your ears, locked in a struggle against lethargy and inertia. A private pep talk which keeps tripping over its own memories, perhaps. Iceboy Violet alternates between swimming through Nueen’s beats and riding on top of them. Voice and music perfectly poised on the precipice of anguish, despair and frustrated jolts of activity. It’s rare at a festival focused on ‘experimental music’ to witness a set so transparent and emotionally raw, even more so to experience it performed in such a direct, intense and human way. The context makes this music even more impactful than on record. Iceboy Violet publicly wrestles with personal demons. It’s so effective because, as well as sharing the despair, they also share the salve.

Eomac, Saint Abdullah and Rebecca Salvadori

Irish producer Eomac, Iranian-Canadian duo Saint Abdullah and filmmaker Rebecca Salvadori team up for ‘A Forbidden Distance’. Only one of Saint Abdullah, Mohammad Mehrabani-Yeganeh, is actually present in Braga. But while his brother and bandmate Mehdi is not here in person, he’s undoubtedly present in the piece’s visual and textual element. Sonically, they move through frenzied beats and more contemplative electronics. These sounds accompany an audio-visual collage of Mehrabani-Yeganeh family home videos and interviews, with subtitles weaving further poignancy into the assemblage and adding detail to the joyful sensory overload. The borders between the different media are seldom clear cut. Audio from the films gets sampled in real time. Subjects of documentary interviews morph into MCs. The relations between the different elements are left open for the audience to thread together themselves, but the playful overlap is effective. Language, visuals and music weave into a poignant, richly layered whole. The ferocity of the beats reorientates innocent home videos into statements of resistance. The textual annotations and narrations expand the meanings of sounds and images. The visual glitches and manipulations suggest that what’s in the past is still active in the present. About three quarters of the way through the set, the line “Performances are movements where you move in and out of sync,” appears on the screen. It chimes perfectly with the magic of what we’re witnessing. Different yet tethered. A celebration of connection in defiance of distance. A prying apart of borders occurring before us in real time.

Moritz Von Oswald

The festival closes with a new venue for Semibreve, the Basilica dos Congregados in the centre of Braga. Moritz Von Oswald’s set is primarily built on material from his 2023 record Silencio, and he’s joined by an 16-person strong Chamber Choir from the nearby University of Minho. Opening with a tapestry of dusty, undulating synth sequences that melt into tingling hi hats and throbbing beats, for the first quarter of an hour of the set the choir are silent as the electronics warp and bend. When the voices finally enter, it’s breathtaking. Staccato lines taking the place of percussion, or moving into intricately phased patterns of long and slow melodies. They integrate completely into Oswald’s music, choir and electronics are completely symbiotic, making this more effective than a techno producer ornamenting their music with acoustic instrumentation. Silencio marks a new step in a career full of new steps for Von Oswald, from basically inventing dub techno with Basic Channel to working with Detroit techno innovator Juan Atkins as Borderland. But the set at Semibreve is also completely rooted in Oswald’s world. Beats are more prominent here than on the record, furthering the impression that the Silencio material is being woven into the longer interests that have shaped his music: The live manipulation of sounds at the controls of mixing desk, the embrace of unstable textures, echo drenched acoustic percussion, a meticulous attention to the sound of the kick drum. Towards the set’s end, Oswald toys with a hi-hat loop, adding and subtracting echo, EQing it out of shape, fading it in and out. It’s a sculptural approach to detail which pervades his music, whether it’s appearing in a church or a club. The whole set is an apparition, at points huge hits of bass hit resonant frequencies and the beautiful church starts to rattle and shake, as if the sound is crossing over from the auditory to the architectural. At others, the voices soar while sound mutates around, textural drifts solidifying into body consuming rhythms. It’s spectral music in every sense of the word. Masterfully embracing sound’s potential to be physical and utterly ghostly. It’s the perfect end to Semibreve 2024.