From the outside, the Congregados Basilica is, like the rest of Braga, beautiful in an understated kind of way. It’s a city where you have to strain just a little to catch the sunset at the end of a narrow medieval street, pause for a minute to notice the way old and new buildings subtly juxtapose. Slotted as the Basilica is into a terrace of shops and restaurants by the side of a busy pedestrian thoroughfare, at ground level you could easily miss its unremarkable front door. Only by stepping backwards into the crowds and looking up will you see the elegance of its twin bell towers.

Inside, however, it is almost intimidatingly beautiful, resplendent in its gilded blend of baroque, rococo and neoclassical flourishes. On a mild October night, the space is made more dramatic still by rich blue underlighting in the chancel, stretching the shadows out long. Dwarfed beneath an enormous altar, Heinali unspools the quietest of electronic hums, while Andriana-Yaroslava Saienko sings delicately, her voice subtly dancing atop the buzz. This performance, a tribute to the 12th century nun and composer Hildegard of Bingen, interprets two of her compositions via a blend of drone and liturgical chants. It is also a masterful display of how the subtlest shift can cause the most dramatic of effects. In the first piece, dedicated to the Holy Spirit, Saienko’s singing dazzles at the forefront while in the background the drone rises so slowly in volume that it is almost imperceptible. Until, like the proverbial frog in warming water, you realise that it has grown into a rolling, scalding boil that floods the room. Then, an extra push of bass ups the intensity even more. Now it’s not just the archways but every fold in the statues’ carvings that the sound pours into. The second piece, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, begins with a clang from the bells above us, then maintains this exploration of shifting volume while pairing it with a new emphasis on tempo. Heinali’s drone shifts into a kind of warble, like an undersea bugler. Saienko’s words become more pronounced, the consonants enunciated and the vowels stretched. Where before the two performers were moving in tandem, now they egg each other to move quicker and quicker. As they crescendo, now it’s as if the sound is not just filling the church but inflating it, like we’re being lifted above the ground.

So begins the 2025 edition of Semibreve, in the organisers’ words “an exploratory electronic music festival” who place particular emphasis on site-specific performances. Braga is particularly blessed when it comes to interesting interiors; there is a chapel belonging to the town’s seminary, for instance, where the original 1940s walls enclose a modern hangar-like structure, which in turns houses a spindly wooden construction. Here, with the aid of a string quartet, Ava Rasti presents The River, a slow and meditative piece inspired by the Piave River in Italy, and the the tension between its peaceful present-day and the historic conflicts it’s been witness to. With the audience arranged to the musicians’ right and left but leaving an empty channel running through much of the space, it’s easy to imagine the waters now flowing through this curious room.

Then there is the episcopal palace in the centre of the old town, a mish mash of the original medieval structure, later expansions, and repairs after a 19th century fire, and which now belongs to the University of Minho which was founded in the 1970s. In one of its older halls, the Lebanese multi-instrumentalist Yara Asmar performs her project Stuttering Music, which encapsulates, like this collaged space, the fact that what appears fixed on the surface is often the result of fragmentation – albeit through the lens of her personal and familial history. Playing an accordion that once belonged to her grandmother, the instrument wheezes and lurches as she lays down an initial melody. I don’t know if it is an old melody or a new one, but the way Asmar plays it lends a warped and battered beauty that makes it sound as if it has been playing over and over for centuries. Then, she loops the instrument, blending it with electronic drones, glockenspiel (which she strikes traditionally for a chiming melody but also scrapes with a violin bow to create a haunting finger-on-wine-glass swoop) so that they mesh together into a fluid and ever-shifting whole. Sometimes the accordion and glockenspiel are so manipulated that they become detached from their sources, almost unrecognisable as the products of those instruments, but at others it’s the opposite, earthed in the clangs of metal and the creaks of wood and leather that she wields.

Semibreve’s most impressive space of all, however, is the Theatro Circo. Whereas the basilica, the palace and the seminary are used once each, this is the festival’s central hub, hosting six concerts over three days. It is beautiful, the inner hall and its three storeys of stalls plastered in white gold and rose, an enormous chandelier hanging at the centre of a neo-baroque cupola – and yet the acts that respond most effectively to the space – Suzanne Ciani and Actress in a collaborative show – do so by stripping those frills and focussing on pure geometry. Standing opposite one another, Ciani behind a tangle of wires on her modular set-up, Actress behind a laptop, they deploy a quadraphonic surround sound set up so that the immense waves of noise they create whirl around and around the circular building. To hear it is to be placed into the centre of a sonic hurricane, witnessing its eyewall sparkle, pop, throb and pulse, accelerate and decelerate in pace, swell in size and recede. At times the whirl has a deep groove, and at others a shredding intensity. It is a shame that the pair are dogged by technical issues towards the end, for when it was within their control, this is as staggering a sound as can be imagined.

For the rest of the Theatro’s programming, it makes more sense to seek threads between the acts themselves than a dialogue between performer and venue. it feels notable that almost all of them, for instance, are playing with light. This is most obvious in the case of Rafael Toral, who launches his new album of jazz standards transformed into languid ambient epics, Travelling Light. Behind him is a screen displaying one shot after another of sunrises over airports, the point at which artificial lights start to war with the crescendo of the rising sun, cut through by long exposure shots of the light trails left by aircraft taking off. Joined at different points by Pedro Alves Sousa’s smoky saxophone, Bruno Parrinha’s moody clarinet, Clara Saleiro’s elegant flute, and most strikingly of all by Yaw Tembe’s rich flugelhorn, and at one point by all four, the music draws out a rich melancholy from the scenes, that mixture of fatigue and strange elation one feels when awake while the rest of the world sleeps.

After Toral, the auditorium is pitch black once again, into which Marta de Pascalis delivers heaving ebbs and flows of analogue electronics, sometimes crashing in enormous waves, at others slowly enveloping like thick smoke. Again, it’s made all the more transfixing by light art – collaborator Marco Ciceri conjuring cracks of lightning, delicate spotlight dances and transfixing triangular beams. The following evening, Lucy Railton deftly sweeps back and forth across the noise spectrum, at times unfurling rich and warm drones, at others making a viola sound like a chainsaw, but again it’s the way her work interacts with that of her two collaborators, the films of Rebecca Salvadori and in particular the sculptural light art of Charlie Hope, that pushes things into the remarkable. Railton is flanked by two asymmetrical reflective monoliths that rotate as if powered by the sounds she’s producing, speeding up when she rushes up the volume, then slowing when she reduces it. They refract glaring beams that shift to a remarkable degree in intensity, warmth and shape – light transformed into a living being.

Following Railton are Emptyset, and yet again the Theatro is plunged into darkness. There’s something theatrical to what the pair do with it; to begin, a single lamp emits a beam of unbelievably powerful light. With Emptyset laying down a gargantuan chug (this old hall boasts a surprisingly intense sound system), it’s as if the noise they’re making is the rhythmic splutter of an old diesel engine, powering a ragged little boat through choppy waters in the dead of night. The beaming light is their only guide through the darkness, their rig their navigational tools. Later, a spotlight roams the audience, so bright it strains their eyes as it passes, and after that – as the sound ramps up to maximum psychedelic intensity – a sublime conical vortex hurtles out from the centre of the stage. The music is a sustained attack of synapse-frying bass and fraying noise, which in tandem with these burning lights frequently threatens to tip over into something outright distressing – but Emptyset manage to delicately toe the cliff-edge, thriving off the tension.

Semibreve is unabashedly intellectual in its programming. During the daylight hours they screen Susan Schuppli’s meditation on the historic complexities of the ice trade Moving Ice, host compositional listening workshops and academic lectures (lectures, not talks). It is testament to the community they’ve managed to establish over the last 14 years that no one seems to baulk at that fact. Nevertheless, all the conceptualism does occasionally threaten to become oppressive; there are only so many combinations of light and abstract noise that can be handled within a weekend. It is helpful, then, that into the late hours of Friday and Saturday the focus shifts from the Theatro to the contemporary arts space Gnration for a separate late night programme. There’s plenty to blow the cobwebs off here – thunderous solo drum-and-noise from NAH, Mike Paradinas’ performance of the manic bangers on 2024’s Grush with live psychedelic/brainrot visuals from ID:Mora, and above all a show from Aya, deep into Friday night.

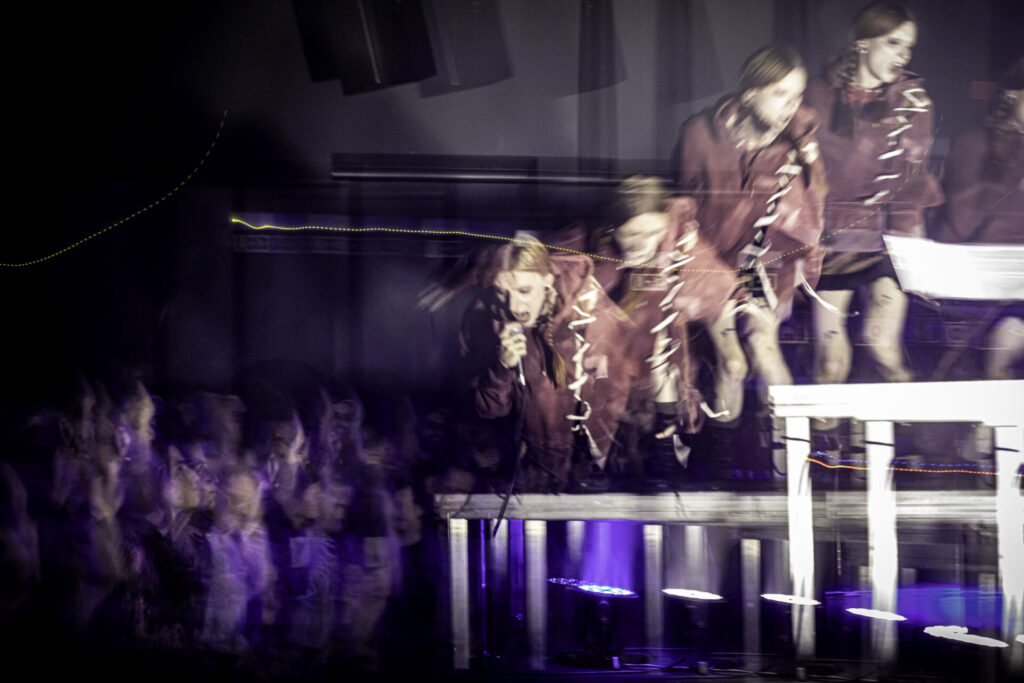

Like her astounding new record Hexed! it’s an engagingly messy affair, Aya as restless in sound – switching between heavy electronics, hardcore noise and high-tempo doof, her labyrinthine vocals shifting in and out of different treatments – as she is in body. At times she locks into the noise, and at others she clambers around her rig, back bent and limbs swinging. You suspect that some of the Northern English nuances in songs like ‘Off To The ESSO’ and ‘The Names Of F*ggot Chav Boys’ is a little lost on the Portuguese crowd, however. When she receives a whoop from one poor viewer after namechecking Yorkshire she barks back “NO! BAD!” and interrupts herself frequently to take potshots at an audience who could certainly be giving her more back – “Come on, I thought you guys loved cocaine?” But then, confrontation is so at the core of this spiky and unsettled music that it works in her favour. She’ll self-deprecate too, interrupting one punishing sequence to call herself a “fucking Kavari tribute act or some shit,” albeit in the same breath as a dig at some fellow billmates (“actually, it’s an Emptyset tribute act, but ten years ago when they actually used a fucking kick drum.”) Amid a weekend of such considered and challenging conceptual performances, it’s refreshing to let things collapse for a while into such mania. It’s testament to Semibreve, too, for crafting an environment where the two can so easily co-exist.