Robbie Williams live at the O2, photo by PA

For a specific type of man, the appeal of packing it all in and heading out on the open road as a Robbie Williams tribute act has always held a certain intractable appeal. Why wouldn’t it? In the imitation entertainment industry, he is widely understood as having one of the lowest barriers to entry in the game. You can write your own cheque as a Queen or Amy Winehouse tribute act, but there’s a complex skillset inherent to those acts. Not quite so Robbie. Turning not very much into success – and, fairly or unfairly, the consensus has always been that he does not have very much – was the Robbie Williams gamble.

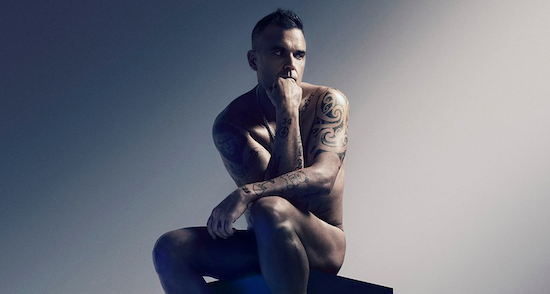

During his late 90s and early 00s imperial phase, Williams was a definitive icon of English masculinity. He has sold over 75 million albums globally. His chart statistics leave Elvis standing at the gates; only The Beatles have had more Number One albums. In 2022, though, he has not had a serious hit single for a decade. Making peace with his own position in the market, he has just released an orchestrated album of his greatest hits, complete with tasteful nude sleeve. Nearing fifty, he is Mr Saturday Night, Mr Christmas. Why, then, does he seem happier than ever, and what might his success and story tell us about the English masculinity he often represents?

Robert Peter Williams was born in 1974 to an upwardly mobile working-class mother and a frequently absent light entertainer father. Aged fifteen, he flunked his audition for the nascent Take That, but was hired after winking at manager Nigel Martin-Smith on his exit from the session. In that wink, Martin-Smith correctly identified that the boy had a certain gawky appeal that transcended traditional notions of talent and competence. Take That were an uneasy coalition built around the haughty child prodigy Gary Barlow, five young men — boys, really — with no idea how to communicate with one another. It was in that group that Williams began to experience the sharp feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, fear, body dysmorphia and depression that would persist throughout his entire life. In 1996, he was sacked from the band owing to his increasingly frequent benders, and was birthed into the showbiz London of the late 90s.

The lad culture of that decade had been partially engineered as a response to the perceived gender play and rising political awareness in a lot of 1980s culture. A now mainstreamed football culture, a growth period for Big Alcohol, an imported and misappropriated postmodernism, a sharp rise in cocaine availability and a nationalistic, back-to-basic moments in guitar rock created a uniquely ugly cultural milieu. Williams arrived at the Britpop party at the exact moment that the bottles were being cleared away and the taxis ordered. With Guy Chambers, a jobbing songwriter who had led the unsuccessful 60s influenced pop band The Lemon Trees, he began his solo career mining key Britpop tropes, revealing his belief in that movement’s superiority to the pop he had produced with Take That. It worked, but Williams’ gamble for solo fame paid off at the exact worst moment for an addict like him, who was at that point only at the beginning of understanding what was leading him to dissolve complex feelings in lager, ecstasy and cocaine. It would make for an unhappy fame, but it did create a back catalogue that’s suffused with Williams’ genius for, in his words, “turning trauma into something showbizzy.”

“Is it a safe space for me to share?” yells Robbie Williams, wearing a gold lamé vest and joggers, with a part-mullet, part-quiff that only emphasises his resemblance to a benevolent himbo Morrissey, “can I be vulnerable for you?” Tonight is going to be a little different. Tonight, the opening night of his XXV tour, we are going to go on a journey. Picture the finale of the biggest pop show you’ve been to, and a Robbie Williams set begins largely pitched at that level, with the high-octane pop/rock bombast of ‘Let Me Entertain You’, followed by a spirited, holiday camp rendition of Wilson Pickett’s ‘Land Of 1000 Dances’. “Tonight is a 32 year musical odyssey,” he explains, sat on a raised podium that is his base for the set’s moments of reflection and reminiscence, “there’s going to be the highest of highs and the lowest of lows, it will be very bleak for me and very emotional for you.” Tonight’s set, then, serves as a kind of biographical greatest hits delivered in loosely chronological order. We are shown an unreleased, early Take That promo video that involves a dancer eating jelly from the chest of Gary Barlow. The video pauses on a pert naked bum. “I’d like to say that was my arse,” reflects Williams, “but it isn’t, it’s Mark Owen’s,” and he uses the moment to reflect on the body image problems that have been part of his mental health struggles. Noel Gallagher cruelly referred to Williams as “the fat dancer from Take That,” and tonight Williams covers ‘Don’t Look Back In Anger’, partly a reflection on the Britpop era (looking wistful as he remembers arriving at the 1995 Glastonbury Festival “with a pocket full of cocaine and a belly full of champagne”) and partly an audacious landgrab of his rivals’ material. Underlining the long 90s theme, tonight’s show is at the former Millennium Dome, that visual emblem of Blairism. Blair and Robbie’s fortunes were intertwined, Robbie’s imperial phase almost exactly matching the Blair premiership. Robbie Williams was the sound blaring from car stereos and workplace radios during those strange boom years.

“I only have two kinds of songs,” observes Williams tonight, “I’m fucking amazing, and you’re lucky to be in the same room as me,” there are cheers, “and type B, which is I’m lost, scared, lonely and vulnerable.” The Robbie Williams imperial phase was strange. For big, million-selling pop songs, their experiences are seldom universal, but often specific to the high drama of his life in the tabloids during those years. The global smash of ‘Feel’ and the early Britpop aping ‘Strong’, both aired tonight, are songs of masculine sadness on a grand scale. “The success broke me,” reflected Williams in a recent BBC special. “You wouldn’t have wanted to spend a second in my head.” That the major English pop star of the early 21st century was a man in mental health crisis is interesting, and perhaps revealing of why the star was able to access parts of the male psyche that other artists couldn’t.

Though he spoke to maleness, a huge part of Williams’ active fan base is, of course, female. One of my earliest, most treasured pop memories is my grandmother, mother and younger sister all sat in hushed reverence for a festive Robbie television appearance. Not many artists get all three generations, and the blockbuster success of Williams’ 2001 crooner album Swing When You’re Winning – which included a duet with the dead Frank Sinatra – helped turn pop’s bad boy into an entertainer for all the family. It helped that Williams was closer to a pre-Beatles understanding of a male pop star, where the songs were just one branch of the all-round entertainer. He positioned himself as a kind of self-appointed wayward son to a nation. “I’m scum and I’m your son, I come undone,” he sings in yet another of his huge, sad hits. Tonight, in one of the biggest cheers of the evening, Wiliams asks, “am I still your son?”

Of course, Williams’ relationship to his female contemporaries was and remains complex. A centrepiece of live sets in the early 00s that would not fly today involved the singer bringing a fan up to the stage, who he would promptly get off with. Listening to the audience’s screams on the footage, audiences appear to be OK with it. As always with laddism, though, you didn’t have to look far for its obvious and grim flipside – see the unpleasant footage of the gurning, worse-for-wear entertainer repeatedly propositioning a patient and visibly uncomfortable Fearne Cotton during Live 8 Tonight, he singles out ‘She’s The One’ to a woman in the audience, and the arena cameras remain fixed on her throughout the duration of the song as an intended respectful tribute to his female fan base. At one point, a woman lifts up her top to expose her breasts for the singer. He is unruffled. “It’s like being a diabetic in a cake shop,” he explains, batting the moment away in words you sense he has had to use before.

“I’m not naturally gifted with what would be deemed a proper talent,” explained Williams in a 2021 interview on The Adam Buxton Podcast. “What comes out of me is pure pop, it’s simple, it’s Middle England, that’s where I’m from.” It was the kind of wallpaper ubiquity that made Williams hard to really observe during his peak. “The sickness that afflicts Robbie Williams,” wrote the late cultural theorist Mark Fisher in 2007, “is nothing less than postmodernity itself […] He is the ‘as if’ Pop Star – he dances as if he is dancing, he emotes as if he is emoting, at all times scrupulously signalling – with perpetually raised eyebrows – that he doesn’t mean it, it’s just an act.” I’m not one bit sure this was what was going on, however. More so than undercutting his own performances with knowing irony, in his imperial phase there was often a worrying lack of irony or distance in Williams’ performances. He expected too much from the stage, he performed as though it could bring salvation. It was neediness in excelsis.

“I can’t stand the way I perform,” mourned an unhappy Robbie in the 2001 tour film Nobody Someday, “I want to be David Bowie or Iggy Pop, but it’s more like Norman Wisdom. It’s like a Tourette Syndrome that I’ve got. A Tourette Syndrome of pantomime movements that I can’t stop myself doing.” Tonight, Williams seems at ease with the strangeness of his movements – and they are strange. Watch a Robbie tribute act, and their wiggles, gurns, squats and shuffles are unseemly. You don’t want to see it. But like all truly great performers, Williams himself always appears galvanised and elevated by some supernatural force.

As the pressures of touring increased, Williams was mocked in the press for bringing best friend Jonathan Wilkes on tour. In Chris Heath’s Reveal book, the singer speaks of needing his friend to be “my walker, hold my hand, and shoulder some of the glare” on tours that the singer had often stressed to management that he felt mentally unable to do. When Williams developed agoraphobia, he would seek refuge in the online world – chiefly conspiracy theories, UFO research and the paranormal (Robert De Niro in 2008 was surprised to be gifted a DVD copy of Living TV’s Most Haunted series by the singer). Some of his explorations are undoubtedly funny, but it is worth noting that the vulnerability of lonely men to online radicalisation by the far-right remains one of the biggest challenges to modern masculinity, not helped by Covid lockdowns and a coming winter that will see many confined to their homes out of fuel poverty.

“A quick update about myself,” smiles Williams as the set nears its close and the narrative reaches its denouement, “it turns out there’s a happy ending.” After a self-described low point in 2006, he began to quietly make changes that persist to this day. He did a lot of therapy, committed to sobriety and embraced fatherhood and marriage. Now sat, for some reason, in a long velvet dressing gown that seems to symbolise his hard-won Zen wisdom, he reels off the names and ages of his kids and pays tribute to his wife, the model and actress Ayda Field. The family redemptive arc is moving, though it’s still something to be denied of women in pop. Singers like Sophie Ellis-Bextor or Jessie Ware may do podcasts based around discussion of family life and motherhood, but what men and women are celebrated for in pop as they grow older remains sharply divided along gender lines.

Robbie Williams on the cover of XXV

Celebrity self-improvement can be hellishly annoying, but the fun of current-stage Robbie – showcased tonight – is the sense of someone not holding back the extreme parts of their personality whilst still making those necessary changes. He does not always get it right – like the video of him singing ‘Let It Go’ from Frozen as his wife actually gives birth – but the redemptive arc of tonight’s set at no point feels smug or self-congratulatory. On a recent The Graham Norton Show> appearance, the actor David Tennant gently chided Williams about possible use of Photoshop on his recent nude album artwork (some of the worst experiences of my life as a man have involved gentle chiding.) With disarming sincerity, Williams rejects the premise of the joke, before sincerely and disarmingly discussing his own weight fluctuations and the body image anxieties that have existed throughout his adult life. In 2023, we can expect that in a biopic Better Man and a planned retrospective Netflix documentary series may help us closer understand one of our most interesting, hiding in plain sight pop performers. “There is always a dichotomy with my career, what I have to do in public as opposed to who I actually am in my real life,” explains in a recent Vogue video, “at the moment, the two are getting closer together.”

There’s a lot of causes for despondency when it comes to being male in 2022, but parts of Williams’ story have had the capacity to give me a strange and perhaps unwarranted sense of hope. Faced with innumerable challenges, it is easy to be pessimistic about the capacity of English masculinity to change. Male suicide remains the biggest single killer of men under the age of 45. There’s a media conversation about male mental health and a changing masculinity that, whilst potentially admirable, feels elitist and distant from those it needs to help. Any solution that foregrounds the relatively easy win of men having conversations with their male friends over, for example, the need for colossal emergency investment in adult and teen mental health services, how the hostile environment created a climate where some BAME people feel afraid of engaging with mental health services, the fact that Black men are ten times more likely to suffer psychosis but half as likely as their white counterparts to get treatment, the role of Big Alcohol in male suffering or the fact that if you’re having a mental health crisis the first professional you are likely to encounter is a police officer, is not even beginning to take seriously the scale of the solutions warranted.

On the ground, though, there are green shoots. Putting one’s faith in general change should always be done with extreme caution, but there is enough evidence to suggest that we are witnessing a younger generation that seems to be dismantling gender binaries (and the itinerant vanguard of teenage male bullying, homophobia and masculine policing). This feels like a huge advance for individual human freedom and should be treated as such. The nadir of the 1990s feels a long way away, but rather than be complacent about this, we should be careful to use this moment to midwife and nurture alternate versions of masculinity, of ways of being male.

Filing out of the O2 Arena, it’s none of the giant pop smashes that really remain in my head as I exit. Not the blockbuster cameraphone moment of ‘Angels’ – the 1997 single of such broad masculine power that it features in the Desert Island Discs of both Peter Schmeichel and Ed Miliband. We are used to hearing it bellowed out in public, its communality comes as no surprise. No, it’s tonight’s performance of the 2016 track ‘Love My Life’. The second single from Williams’ 2016 album The Heavy Entertainment Show (that album’s primary single, ‘Party Like A Russian’, has been retired for obvious reasons), ‘Love My Life’ taps into something that has always been a Williams trope but now appears to connect this most arcane of performers to the modern pop moment. “I am powerful,” sings Williams, perhaps at his most enthused during the set, “I am beautiful, I am free, I love my life.” Not much about Robbie ever seemed likely to predict the future in pop music, he wasn’t that sort of guy, but the bombastic confessional song he pioneered during his imperial phase quietly became the lingua franca of mainstream UK pop. The dramatic, confrontational self-revelations of Sam Fender and Self Esteem were not really a feature of British pop before Robbie. What really is the Robbie Williams story? Tonight, it’s one of a boy from Stoke-on-Trent not only changing himself, but also changing British pop.

Robbie Williams’ XXV Tour continues across the UK and Ireland through October