During our Wednesday evening flight to Turin, a businessman roughly unfolds his copy of La Repubblica, Italy’s once-socialist, now centre-left newspaper, and flattens it on his lap. He’s reading a story about Dave Grohl, pictured onstage on a red light-up throne in the city of Cesena. The previous week, 2000 musicians had lured Foo Fighters to play the small comune after uniting in a field and covering ‘Learn To Fly’ en masse. Written in Italian, the article’s headline heralds either a revolutionary celebration, a celebratory revelation, or perhaps the author’s revulsion at celebrity. The businessman, with furrowed brows and hair crawling out his nostrils, is reading with that air of violated importance you often see in well-heeled men flying economy. The next night, I stand among a rapt Club to Club crowd and tipsily contemplate socialist revolutions and revulsion at celebrity while watching SOPHIE and QT, who have points to make on these topics.

What exactly those are takes a minute to unpack, but in many respects, there couldn’t be a better arena to do so than Club To Club 2015. Like the QT project itself, the Italian festival is a theatre of extremities. For its 15th anniversary, the curators have significantly airbrushed the lineup – welcoming Thom Yorke, Jamie xx, Nicolas Jaar, Floating Points – while remaining anchored in sonic grotesquerie (Powell, Carter Tutti Void, Oneohtrix Point Never, many more anarchic terrors). The contrast is a joy: on Friday night, gasping for aural relief during Thom Yorke’s moody, enveloping Tomorrow’s Modern Boxes show, we skip through a corridor and discover the sonic wonderland of Antony Naples’ DJ set. The New York producer plays a generous mix of funk, soul and techno; following Yorke’s tetchy bass workout, it feels like we’ve skydived into a ball-pit.

What sets apart the QT project, with its heavily conceptual agenda and irrepressibly visceral hooks, is that it is both the vertigo and the ball-pit. Although they’re loathe to confront politics directly, the duo – comprising producer SOPHIE and a New York performer named Quinn – are, along with the related PC Music brood, deceptively in tune with our socio-economic conversation. Their music confronts you with indulgent, excessive symbols of consumption (one PC Music song features a playground chant about money served on gold plates) then uses maximalist production, impossibly cute vocals or disembodied beats to leave a nasty taste. The uncertain role of women in the collective – often seen as male producers’ pliable playthings, a reading that perhaps undersells their input – only deepens the queasiness.

It’s hard to talk about the music without acknowledging Red Bull, whose logo hangs over the bar and second stage at Club To Club like a spectre. As a combined musical duo and promotional energy drink, QT possess uncanny similarities to that brand and its quasi-underground Music Academy. Whereas Red Bull has invested selectively in dance music culture to strengthen its brand, QT are the precise inverse: they harness a cosy relationship with commercial symbols and ad-speak to reap artistic profits. (Notably, SOPHIE’s peers at PC Music just signed a major label deal with Columbia, thus ensuring the profit enters their bank accounts, not those of a fantasy art-project simulacrum.) It is music as cunning as any marketing campaign, smudging the lines between satire and sincerity, high and low culture, to challenge the logic of binary distinctions. In this world authenticity of any form is suspect, and concepts like taste and gender are presented merely as aesthetics with which one should, uninhibitedly, fuck.

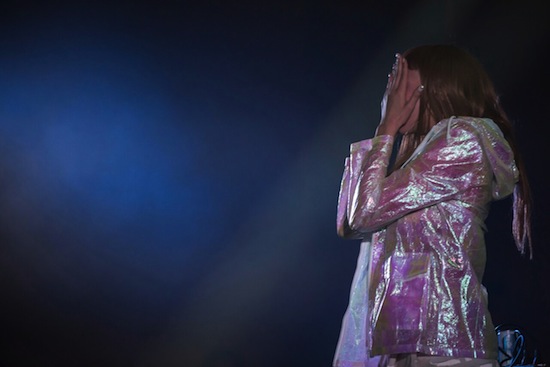

QT is best-realised performed live and with serious volume. We first bear witness to her presence midway through SOPHIE’s DJ set, when she bursts onto the dance floor wiggling to Charli XCX’s ‘Girls’ Night Out’. In white heels and headphones and a glittery coat, she illustrates the tune’s philosophy (key lyric: "girls night out; no boys allowed") with a mock-serious finger-wagging dance, sometimes getting yanked aside for selfies. Then she saunters onstage and performs three pristine pop songs that are also songs about pop, right down to demystifying the term’s etymology. One new track has a carbonated, chantalong chorus – "Baby bubbles so big they blow!" – so brilliantly moreish the comedown is under way before the song is over.

Yet between tracks, something cracks in QT’s facade. She lets a strange ennui crinkle up her features, the look of a sentient wind-up toy realising it’s out of juice. When the tune whirrs up and she jerks back to bounding, saucer-eyed life, you react with discomfort and a strange sense of guilt – but it’s also emotionally deep. Though critics dismiss the project as wilfully divisive, the intended response, it seems, relies on a more nuanced kind of quantum logic. We’re not supposed to love or hate, but to exist in both states at once.

For all that, the QT experiment is not always enjoyable to watch. In reality, we can’t express scepticism of pop’s squirmier elements at the same time as blind submission to the music. Last year in Shoreditch, I witnessed the disturbing spectacle of a crowd performing the ‘ecstatic surrender’ response, when PC Music boss A.G. Cook dropped ‘Hey QT’ into a DJ set and prompted an embarrassingly posh stage invasion. Anyone with a quantum of reservation, in such a scenario, must step back. Tonight, as a pool of diehards pump their fists to the finale of ‘Hey QT’, I notice a few fans caught in the in-between leaving the dance floor. After a brief pause, I become one of them.

If QT’s counter-capitalist strategies make for interesting art – and, to be sure, there are plenty who’ll tell you they don’t – a political response requires good old fashioned compromise, something you can observe right now in Italian politics. Club To Club takes place in Turin, a historically leftwing enclave in the conservative north of Italy. Back in the early 20th century, student Antonio Gramsci fomented Italian communism here before his imprisonment by Mussolini. Recently, Turin’s voters have consistently resisted conservatism and austerity, and now, after a national tug of war between the socialist left and extreme right, the rest of the country is somewhat in sync. Last year, 40-year-old liberal Matteo Renzi took office, clearing out Berlusconi’s corrupt senate and implementing a younger, gender-balanced house. While he’s hardly the people’s saviour (one festival organiser tells me, simply, "we do not trust him") he is a symbol of resistance against rightwing scaremongering. At a time when radical intolerance is sweeping Europe, the instatement of a progressive underdog feels revolutionary by comparison.

Despite the upwardly mobile lineups, Club To Club, too, is managing its ideological tug of war with integrity. Its status as an outsider festival remains intact, not least thanks to its spartan venue, Lingotto Fiere, which evokes a wartime prison cafeteria sponsored by energy drinks. Yet for those of us accustomed to the Field Day model of hedonism – pretty floral tent designs, craft beer served with a smile – there’s something restorative about its concrete vastness. Even the cosier second room, bedecked with a carpet that’s absorbed so much spilt Taurine you could lick it and sprint to Milan, feels peculiarly lifeless. Its starkness suits the music, at once complementing the pallor of punishing sets by Not Waving and Powell while, when the music is euphoric and colourful, enhancing the magical sensation of being elevated from your surroundings.

An example of the latter is Todd Terje, who carries us over the 2am mark on Friday night. As ever, he closes with the transcendent disco anthem ‘Inspector Norse’, its puckish melody dancing round the room like light pinged from a glitter ball. When that revelatory key change hits, Todd looks up and grins. Sated, the crowd goes nuts, spilling Red Bull everywhere.