At the Paul Weller concert, there are surprisingly scant Paul Weller haircuts. Least of all on Paul Weller himself.

Walk past one of the mod themed weekends that are the fixtures of seaside resorts and small market towns, and a fixed type emerges: gentlemen of a certain age in an uncanny panto tribute to the subcultures of their now distant youth. Tonight, crossing the road from Hammersmith underground, the Weller audience – largely but not at all exclusively made up of couples in their 60s – is more, well, normal than one might expect.

As the house lights dim, and The Beatles’ 1966 track ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ pounds its still startling Indian tape experiment fusion over the PA system, London Mayor Sadiq Khan is quietly ushered to a seat nearby my own.

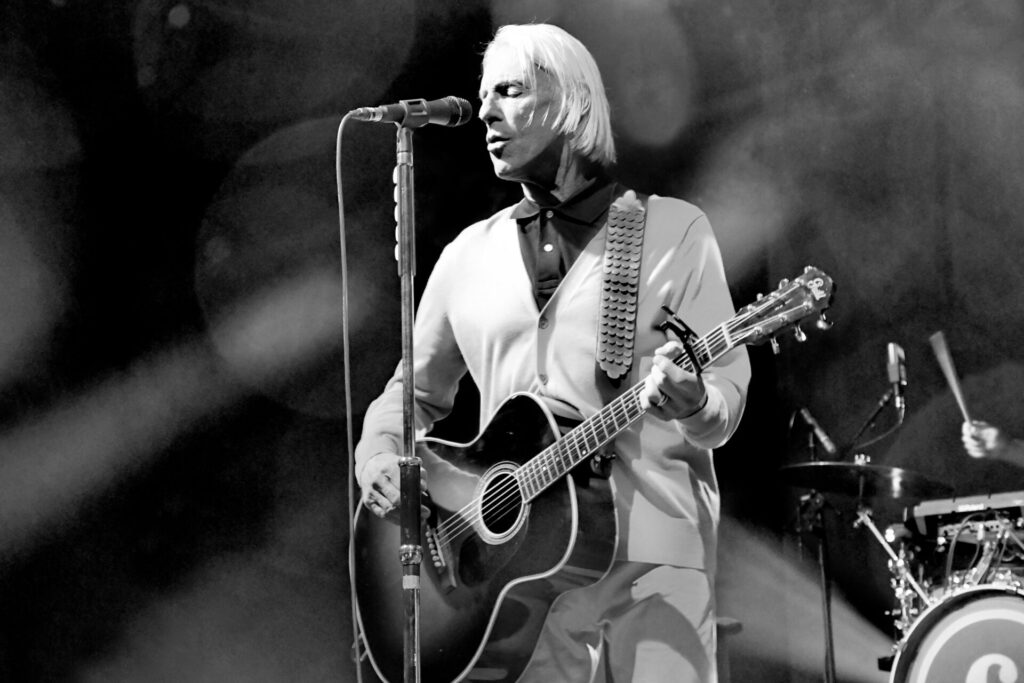

When Weller takes to the stage, in a light denim jacket and dark, tastefully cut trousers, it is with hands clasped in gratitude for the audience whose applause is rapturous without being rowdy. House lights illuminate a large Palestinian flag that hangs from the singer’s piano.

“How wonderful to be back in this city,” says Weller by way of introduction – you would not guess from his rich suntan but his band are on the final night of a tour of Britain and Ireland. “We’re going to play a lot of songs across all the ages. New songs, old, all sorts.”

With the sole exception of the authors of his psychedelic walk-on music, only Paul Weller – born John William Weller in Surrey in 1958 – has topped the UK album charts in five consecutive decades, a run that extends from The Jam’s 1982 The Gift album to the Covid-era solo release On Sunset. Tonight is the final decade of his second tour of 2024, ostensibly to promote his seventeenth album 66 – which sees Weller cede control of his lyrics to collaborators including Suggs and Noel Gallagher, the latter of whom is in tonight’s audience – which was released the day before his 66th birthday this May. This weekend, too, the singer’s first acting role is in cinemas, performing as an elderly Stepney grandfather in Steve McQueen’s Blitz.

Of the three 2020s era songs that begin the show, ‘Cosmic Fringes’ is zipping, if a little conventional, electro pop, with Weller singing in a register equal parts Cockney Bowie and Baxter Dury. More expansive is ‘Soul Wandering’, the gently exploratory modern soul with themes of personal self-discovery that have been one of the few consistent throughlines of his three decades solo career. Historically the most reliable depositor of guitar stodge in British music, on these tracks Weller’s band provide an arrangement with nuance and careful sonic detail, not least Jacko Peake on discordant saxophone and two percussion players, Steve Pilgrim and Ben Gordelier. “This is from an album that was very popular in the 1990s for whatever reason,” says Weller before introducing the two-chord vamp of 1995’s ‘Stanley Road’.

Stanley Road is the Woking street where Weller spent the first seventeen years of his life, in a now demolished Victorian terrace. The teenage Weller, managed by his no-nonsense builder and taxi driver father John Weller, forged an early iteration of The Jam in the town’s working men’s clubs. 2024 is fifty years since Weller’s first full year as a professional musician. That year was the exact peak of working men’s clubs in British life – one in ten adults were members, and The Jam worked over eighty bookings on the WMC circuit in 1974 alone (they were even booked to play a WMC in Guildford on the night of the fatal IRA attack that October.)

“Woking’s a very class polarised town,” explained Weller to the NME in 1979, “there’s a very working class area and then a middle class, rich area, which is very extreme in that sense… we’ve been sort of knocked for writing class songs and that but I feel justified in writing them.” The Jam were chided for being gauche and suburban by an ambivalent music press – “we were,” Weller reflected to The Observer in 1995, “too normal for them” – but this was exactly why their audience believed them over their metropolitan contemporaries. (He has remained loyal to these places: nobody really plays my hometown of Blackburn anymore, but Weller has performed four times in the last decade alone.)

On albums like Setting Sons, or particularly the singles ‘When You’re Young’ and ‘Going Underground’, it was as though, by being confronted each night with his huge working class audience, the songwriter had seen something ominous and important about their futures, that they would only understand years later and look at in reverse. Later, the only critic who really took The Jam as seriously as their audience was Mark Fisher, himself from the East Midlands town of Loughborough. He wrote in 2014 that the band were “more sophisticated and more interesting – politically, culturally, aesthetically – than their more lauded post punk counterparts”, finding them “as bleak as anything Ian Curtis wrote.”

Tonight, following the restrained and downcast plea against prejudice that is 2021’s ‘That Pleasure’, a song that Weller describes as having written following the 2020 murder of George Floyd, the tone of the evening shifts. “I would like to dedicate this,” says the singer, stridently but carefully, “to the people of Palestine and Gaza.” There is huge applause in the hall, and video footage of Weller making a similar speech has been shared on social media across the last week.

“I’m a big supporter of theirs and I’m in sympathy with them, and we just hope for an end to this genocide.” Another pause. “We can’t call it anything else. It is beyond politics and it is beyond religion. To me, it is a yes or no question.” There’s a bit of a disruption – was it a heckle? – and Weller squints to hear the audience member, before softening. “Yes mate, exactly that.”

Tonight, outside the Apollo before and after the show are fundraisers with buckets for Gaza Go Bragh, a grassroots project of Northern Irish and Palestinian volunteers aimed at providing tent, water and cash assistance for those trapped in Gaza. This is on a weekend where the UN’s Human Rights Office has released analysis showing close to 70% of verified victims of Israel’s genocide have been women and children.

This introduces the wah-wah funk guitar opening of ‘My Ever Changing Moods’, the 1984 single by The Style Council. In 2024, it is that band’s legacy that Weller seems increasingly comfortable to commune with, even reforming the band – with Mick Talbot, Steve White and Dee C. Lee, who was married to Weller between 1987 and 1998 – in 2019 for a one-off filmed performance of 1988 single ‘It’s A Very Deep Sea’.

In Tony Blair’s 2010 memoir A Journey, the former Prime Minister recalls a moment of supposed truth-telling after a 1986 Red Wedge concert, the campaigning organisation spearheaded by Billy Bragg and The Style Council encouraging young people to vote for Kinnock’s Labour ahead of the 1987 general election. It was all well and good having “people like Paul Weller and Billy Bragg,” observed Blair, “we need to reach the people listening to Duran Duran and Madonna, a comment which went down like a cup of sick.”

Blair misses the point that Weller was trying to reach exactly those people. The Style Council were a strange entryist project, who had songs declaring their internationalism and donated their royalties to Youth CND, but it was always tightly packaged in the jazz-influenced sophistipop that was then part of the chart mainstream. Tonight, no track gets the upstairs audience out of their seats and dancing more promptly than the 1985 single ‘Shout To The Top’.

There’s an interesting moment where you can speculate The Style Council came to an end. It’s not when their prescient 1989 album of Chicago inspired deep house was rejected by Polydor. No, it’s the Newcastle date of the Red Wedge tour. The Smiths made a surprise appearance after weeks of deliberation (can you guess which member needed the most persuading?). “There was an explosion when they hit the boards,” observed Weller, and it reminded him of the reaction to The Jam a generation earlier. What the kids wanted was not Weller’s Red New Deal, but to wallow in English misery.

Tonight, Weller’s ‘The Changing Man’ – the 1995 top 10 single that marked the zenith of his post-Style Council commercial comeback – sounds staid alongside some of his more dynamic and soulful output. You can learn a lot about the 1990s thinking about the shift from The Style Council to that track, where playful communitarianism gives way to strutting self-aggrandisement (in fact, Weller later said he was asked by Tony Blair if Labour could use the song in the 1997 election campaign.) The newly apolitical Weller suited those years, the mod who came in from the cold. This was the only truly boring era in his long career, pegged as the midwife to Britpop and the more parochial corners of the early 2000s British indie rock revival, the frowning ombudsman of monthly magazine retro taste.

This was the Weller I remember from long summer car journeys as a child, as CDs like Stanley Road and the live acoustic Days Of Speed album were on chronic rotation in my dad’s Volvo. But by my teens, Weller was suddenly making music more adventurous than the British indie bands that I was stopping listening to.

Albums like 2008’s 22 Dreams or 2012’s Sonik Kicks saw one of Weller’s periodical fractures with his own career and history, and you could suddenly find the Surrey songwriter turning in Broadcast influenced spectral pop, homages to Alice Coltrane, spoken word about God, as well as spikier and more abstract new wave than what he had been up to at the time. Between those records, Weller had entered a new relationship with singer Hannah Andrews, embraced sober living – speaking publicly about his alcoholism in the 1990s and 2000. John Weller, who had continued to manage his son into the new millennium, had passed away aged 77.

The records Weller makes now have calmed down from this moment as he moved onto the next thing, but last decade albums like True Meanings or Fat Pop (Volume One), not to mention his 2020 Ghost Box Records EP In Another Room – are shorn of the stodge rock that defined his long Britpop years. The grim reality of austerity Britain even coaxed the old leftist Weller out of retirement for one last job, and in Christmas 2016 he persuaded Robert Wyatt to perform, along with Danny Thompson, a Corbyn concert for Momentum.

This summer, Laura Snapes wrote in The Guardian that “there are songs every British person deserves to hear done live at least once”, correctly citing ‘Angels’ by Robbie Williams and ‘Come On Eileen’. Tonight, ‘That’s Entertainment’ is another, and you’ll have a better time watching the audience than the man onstage. They’re all on their feet, fumbling with their iPhones to take pictures, and you can see their glowing screen backgrounds are mostly photos of their infant grandchildren.

Throughout the set Weller seems relaxed, at ease with himself and surprisingly chatty – more so than one might have encountered a decade ago – reminiscing about sitting at the very back of this same venue on his fifteenth birthday to watch Wings, and that he played the same venue with The Jam only a few years later. “Thank you for being here all of these years, weeks, months, whatever,” he twinkles, dedicating a song to the old boys that had been watching him since 1977.

Close to the show’s end, Weller introduces the Nottingham reggae and soul songwriter Liam Bailey, who has been supporting across this autumn tour, to sing lead on the 1995 song ‘Broken Stones’. “This man is so talented,” effuses Weller, sat at the upright piano, “a great, great writer.” Weller is not a widely covered artist, and the unfamiliar inflections of Bailey’s rich vocal allow the familiar song to land as a surprise, a generous and stirring moment in the set. At the left of the stage, Weller is hushed as he performs the piano accompaniment. Eyes shut, his silver bob swishing with the track’s unrushed tempo, lost in a place that he has been communing with for half a century.