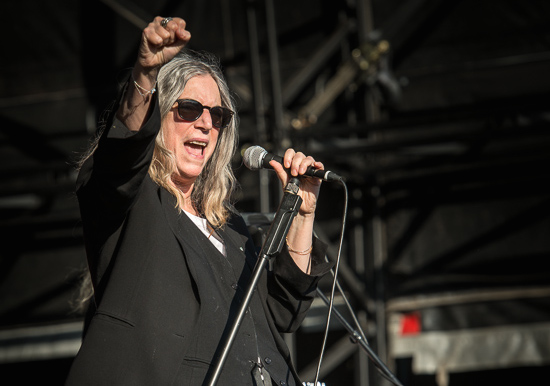

The last great rock & roll performance takes place on a hot sunny Sunday afternoon in a flat green field somewhere near Mile End in East London, and many notice it, and feel a tingling in their senses and a stirring in their blood and almost cry with joy, and some don’t notice it, and wander off for chips. The last legend still being legendary, the last myth being mythical, Patti Smith once again delivers the best her genre could give while simultaneously transcending it.

Like rock & roll, Lou Reed is dead now, but he once said that he "harboured the hope that the intelligence that once inhabited novels and films would ingest rock". It didn’t pan out that way; the redirected red herring of punk made it uncool to use long words or have ambition, and those misfits with ideas different to the herd moved into other genres, other modes of expression. What’s now left of rock & roll – oof, the pungent cheesiness of those three words – is mimicry, karaoke, at best the occasional talented idealistic young person trying to recapture the childish dreams of paradise they discerned in their parents’ record collection.

There was, though, a time when rock & roll had been around long enough to have fired its establishing shots but not so long that smart and sincere artists couldn’t do new things with the characters and dialogue. Words, guitars, drums – people did purposeful, passionate things with them once. Patti Smith arrived at and defined that moment, diving into the sea of possibility. Playing (or working) with poetry, gender, incantations, she was influenced by Sam Shepard and Jimi Hendrix but chiefly by the 19th century French poet Arthur Rimbaud, who wrote in a letter, at the age of sixteen: "I’m now making myself as scummy as I can. Why? I want to be a poet, and I’m working at turning myself into a seer. You won’t understand any of this, and I’m almost incapable of explaining it to you. The idea is to reach the unknown by the derangement of all the senses. It involves enormous suffering, but one must be strong and must be a born poet. It’s really not my fault."

The story and psycho-geography of 1975’s Horses album, Smith’s very New York, very universal, very individual debut, nominally produced by John Cale though Smith’s instincts were different to his, has been documented elsewhere. To hear her and her band play it, in 2015, is electrifying, galvanising, alarming, affirming. Smith is incapable of "going through the motions" or chuckling with a self-effacing nostalgic shrug of "ah, those were the days". (Which is not to say she’s pompous or over-earnest, indeed she’s benign and modest. When I interviewed her, way back, she sent me a thank you note). Once the rhythm takes her, once the words start to tumble and trip over each other, gathering momentum, the treasurable traction takes her to the place where it all happens. Years fall away for the duration of the show, and the young, the old and the middling alike can feel why this collection of music and lyrics and dynamic ebbs and flows and rushes redrew the map of what you could do with a record, with a live set. You could be voices, plural. The levels of intensity a performer could bring, could summon from the gods and demons, were changed. And of course the roles of women within the medium were empowered and radicalised (though I’ve written about that elsewhere on The Quietus and don’t wish to define Patti Smith by gender every time).

Ten years ago, about to play Horses for the first time in almost three decades, Smith told Simon Reynolds, "I wanted to do it while I’m still physically able to execute it with full heart and voice. I had nicer hair back then, but my voice is actually stronger now." She added that she took good care of herself now, because "I want to be around a really long time. I want to be a thorn in the side of everything as long as possible." A decade on, she is both that thorn (in the side of mediocrity) and the last rose in the rock garden.

There’s a spell of about six minutes of chants and chugs and pleas and poise, within the nine of ‘Land’, which are the highpoint of rock & roll’s recorded history, as dementedly exciting as any Dionysiac soup of music and sound before or since. Today’s rendition goes on much longer, goes deeper and wider, yet never loses focus or heat. It’s surely impossible for a set that begins with "Jesus died for somebody’s sins… but not mine" and within minutes races into that appropriated air-punching ‘G-L-O-R-I-A’ chant to keep rising in drama, from there. Yet it does. The loping ‘Redondo Beach’, the sorrowful recitation of ‘Birdland’, the sexy romance of ‘Free Money’, the palate cleanser of ‘Kimberley’: these would be stand-outs in any other show. ‘Break It Up’ could shatter the heart of a victim of petrifaction; ‘Elegie’ too. Throughout, Lenny Kaye and Jay Dee Daugherty and company perfectly gauge the tightrope between annunciating the time-honoured script and flying off into jazz-juiced inspiration. It’s elevated but primal. I register, in my brief interludes between sensuous experience, that this 68-year-old woman is declaring revolutionary surrealist poetry in a big field of sunbathing indie fans, and they are, for the most part, lapping it up. If that’s not "still subversive", what is?

It’s peculiar at first, this music of the night emerging in broad daylight, but she recalls how she was working in a Greenwich Village bookstore in her youth – just kids – when the Stones played Hyde Park and she thought Brian Jones was wonderful and dreamed of playing to a big crowd in a London park. "You’re MY Hyde Park", she laughs. When she misses a cue, she says, "I fucked up. But I even fuck up perfect. So you win."

There’s more, as they relax into ‘Dancing Barefoot’, ‘Because The Night’, ‘Pumping (My Heart)’ and the slightly corny but probably topical and essential ‘People Have The Power’ ("to vote! to strike!"). When not berating governments, Smith sings words like "sublimation" and they fit. Her voice is a marvellous mix of rasping snarls and serene sighs. For the wig-out finale of ‘My Generation’ – both poignantly obsolete and defiantly fuck-you enough not to be – she grabs her blue guitar, coaxes from it random anti-music screams and noises, kisses the neck once and raises it to the skies left-handed. That’s how great rock and roll was, when it was great. "Fear nothing!" she shouts. "Live YOUR life."

Suddenly Johnny gets the feeling he’s being surrounded by horses, horses, horses, horses, coming in in all directions and he has to push down to the front and jump and splash about like a child and the sound and fire is good and the rhythm rises and the most exalted ageless priestess of the ashes and embers of rock & roll resurrects poetry and the sun burns down and the world is momentarily alive and we are all immortal and pure and galloping free.