Grace Jones by Markus Thorsen

I’ve often thought about what it would be like to have a cock, and who I’d use it on, and how much they’d like it. It’s a notion that has popped up many times over the years, although I haven’t given it much Freudian analysis. I did wear a girthy great strap-on to a party once, with a catsuit, red lippy and high heels, and I had an excellent night. It was a lot of fun.

Christine & the Queens’ song ‘iT’ is, as singer and writer Héloïse Letissier has said, “about wanting to have a dick, just to have an easier life.” It’s also a great song. I’ve played it over and over again, singing along: “Cos I got it, I’m a man now / Cos I won, I’m a man now.” It sometimes reminds me of a few other songs I’ve loved and sung along to, like Bikini Kill’s ‘Suck My Left One’, or Patti Smith’s version of ‘Gloria’ – playful and angry, fun and subversive, and really great. Patti Smith once said, “Being any gender is a drag”. It’s a feeling that’s been around a long time, but recently C&TQ and a few others have made me think about it more and more. If gender is a performance, and if performance is fun – at least some of the time – then maybe that’s why pop music is such a good place to play with gender. That’s what occurs to me, at Øya festival in Oslo this year, when I see Christine & the Queens open the festival and when I see Grace Jones close it.

Laurie Penny recently wrote, “I’ve never felt quite like a woman, but I’ve never wanted to be a man, either. For as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to be something in between.” In the wider world it can be – is – a fight to be both, sometimes a dangerous fight. But sometimes – and especially in pop – it can be a lot of fun to be both, or neither, something beyond or in between. In Notes On Camp, Susan Sontag says, “One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious,” and I think that’s what we’re doing when we play with gender in pop music. What are we thinking about, what are we disrupting, where might be we heading? As Judith Butler wrote, “It may be only by risking the incoherence of identity that connection is possible”. So, music lovers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your bullshit binary gender identity.

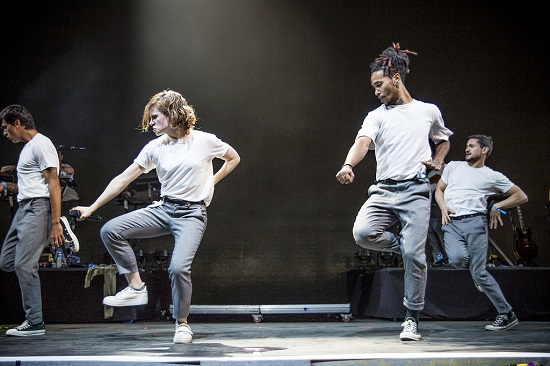

Christine & the Queens opened Øya on a sunny August afternoon – Letissier and her band and her dancers filled a dark, laser-lit tent with swooning fans. On stage in Converse and grey pants and a white T-shirt, with her male dancers dressed the same, she is small, androgynous, cute. She looks very happy. “This is a free zone,” she smiles. “You can be who you want to be, you can change your name.”

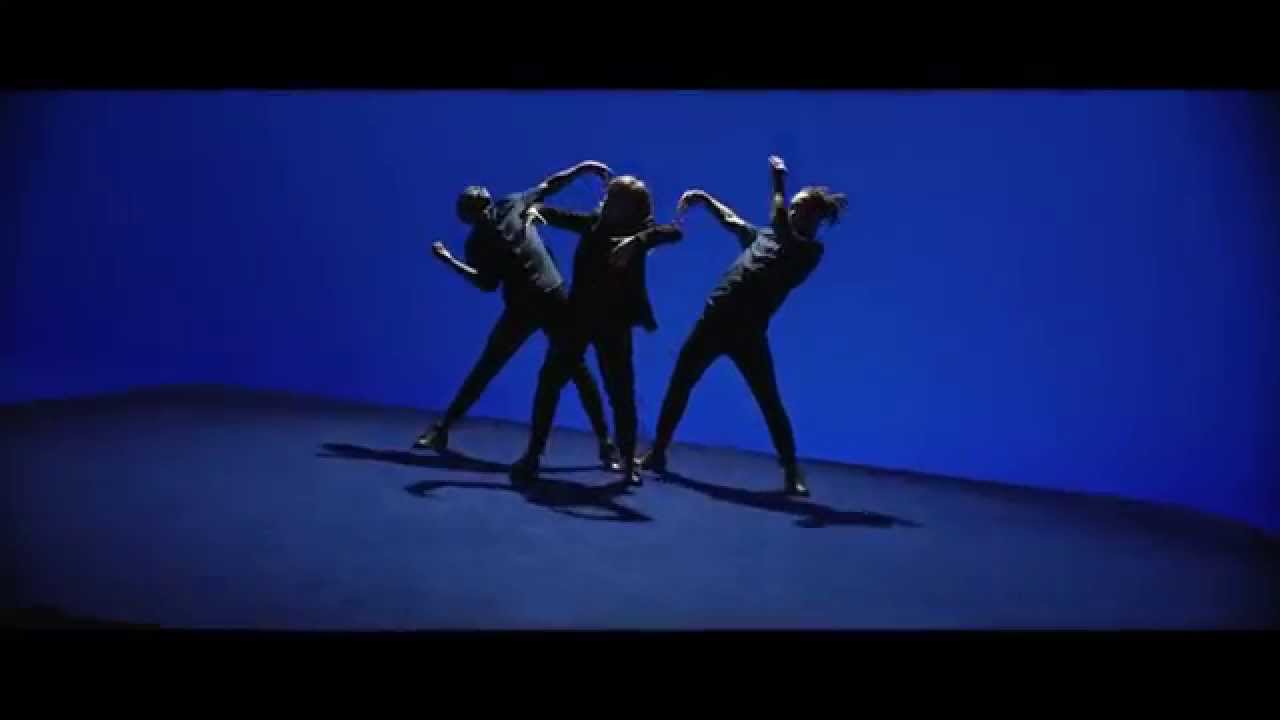

Letissier dances, during opening number Starshipper, like a she is trapped in an in-between place. Jerking, swinging then freezing, half-hatched. Her mixture of French and English, in her songs and her chatting to the audience, also suggests an in-betweenness, or a multipleness – like her androgyny, she has a way of being two things at once, or being neither thing. “For my next album, I’m thinking about not being defined as a girl anymore,” she said recently. “I want my body to be even more androgynous… to have muscles… to defend myself.”

Christine And The Queens by Ihne Pedersen

‘iT’ is the second song they play. Now Letissier’s dancing like Michael Jackson, playing like he did at being sexy, at being sexually dominant, with those pelvis jerks and smooth moves. She shows off her biceps, like a pantomiming Popeye, and gives little MJ whoops. One of her band sings the teasing backing vocal – “She wants to be a man” – and rolls his eyes. There is theatre, camp, between all the dancers. It’s like Pina Bausch mixed with West Side Story. They are playing about and having fun with masculinity and femininity, there’s a loose, jerky synchronicity in their moves – they’re together but not the same.

Letissier sings plainly about the performance of identity, in ‘iT’ (“She draws her own crotch, by herself”), in ‘Tilted’ (“I’m doing my face with magic marker”); in ‘Half Ladies’, she sings, “Always out of place/ but we found a place of grace… Just when you thought I was still a little girl, I’m one of the guys.”

It’s important that this is pop music, with a pop sensibility. It appeals to just about everybody, it’s catchy, it’s fun and, unless you have an extraordinarily brittle idea of gender, it’s completely unthreatening. Looking round the tent, one thing that’s great is how many people love it, how joyful and visible and popular it is, occupying a mainstream space in the centre of things. There’s sincerity and playfulness too: as Sontag put it, “One is drawn to camp when one realises that sincerity is not enough. Sincerity can be simple philistinism… Camp is a kind of love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of character.” Letissier loves that weirdness, that awkwardness. (Sometimes her dancing reminds me of the excruciating sincerity and vulnerability you get in the singer from Future Islands.) She introduces their biggest hit so far – ‘Tilted’ – as “a song about embracing awkwardness. Everything is so straight, and I just feel slightly… Tilted.”

The dancing, the warmth, the openness, the ambiguity, the fun, the sexiness, the multiplicity: what effect does it have on the crowd, on the desire and energy? At the end of the song, it seems like everyone in the tent is grinning adoringly at Letissier. She grins back, “No questions?”

“I love you!” someone shouts from the crowd, ecstatic.

In her recent brilliant LRB piece, Jacqueline Rose digs into the multiplicity of trans – as a transition from one gender to the other, or the transitioning in between, but also as transcendence – she quotes Jan Morris, who said “There is neither man nor woman… I shall transcend both.” Rose goes on: “Even that is not all… non-binary, gender queer, bigender, trigender, agender, intergender, pangender, neutrois, third gender, androgyne, two-spirit, self-coined, genderfluid.”

According to trans activist Jennifer Finney Boylan, “It is not about who you want to go to bed with, it’s who you want to go to bed as.” Something lit up in my brain when I first read that. Cis and straight and thoroughly privileged, I don’t want to co-opt anyone else’s territory. I do want to recognise my own touches of transcendence though. Like: was I attracted to gay male relationships as a young teenager because I wanted to have sex with men but I didn’t like the female option presented to me in hetero sex? Maybe sometimes I feel the way Stella does in OITNB: "I consider myself to be a woman, but that’s only because my options are limited.”

Something lit up, too, when I read Simone de Beauvoir’s famous line: “One is not born a woman, but becomes one.” (I bet Letissier is familiar with that statement, and it’s better in the French: “On ne naît pas femme, on le devient.”) We are all becoming, we are all performing. As RuPaul sang: “We’re all born naked and the rest is drag.” On stage and on the dancefloor it becomes more obvious, that we are playing, pretending to be something and also actually being it, but it’s there all the time.

Whether or not you really relate to any of this, you surely know that those two categories – man and woman – don’t always help and often get in the way of clarity, honest and reality. Judith Butler wrote, “There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender,” and, “Gender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being.” I think she is probably right. I struggle to think of any time when I’ve been aware of my womanness in a way that wasn’t somehow related to men being in charge, or related to the pitfalls of being a woman, and I think it’s the political side of womanhood – reproductive rights, rape justice, discrimination at work – that make womanhood real. None of those things apply to all women though, and they very often apply to men too. So what is the biological ‘fact’ behind the gender curtain? There’s nothing at all, as far as I can see. We are each our own glorious combinations. As trans activist Paris Lees has said: “I am not a woman in the way my mother is. I haven’t experienced female childhood. I don’t menstruate. I won’t give birth. I have no idea what it feels like to be another woman – but nor do I know what it feels like to be another man. How can anyone know what it feels like to be anyone but themselves?”

It’s difficult, maybe, to let go of the gender binary, but it gets easier when you start to realise it’s all made up. I find it gets easier when you find out, as I did this week, that your clitoris might well be bigger than most of the dicks you’ve seen. It gets easier when you see Christine & the Queens dancing and singing great pop songs, and when you see Grace Jones being magnificent and happy with her tits out and her cock on. And it gets easier when you start to think about the damage done by what Toril Moi describes as the “death-dealing binary oppositions of masculinity and femininity”, the myth of a clearly defined, objective, real, fixed gender identity. Julia Kristeva has written about a third phase, a future where we reject the dichotomy of man and woman “times in which the cosmos, atoms and cells – our true contemporaries – call for the constitution of a fluid and free subjectivity”. That sounds pretty good, don’t you think?

In a society that frequently seems predicated on in or out, goodie or baddie, completely right or completely wrong, this gang or that gang, in a society where ‘sex’ still very often simply means putting a penis in a vagina, it is worth cherishing and defending the inbetweens, the mushy and delicate areas, the margins and the fragments and the less clearly defined patches of ground where most of us actually feel safer (where most of us actually are safer), and where we have more fun. Lots of things can be true at the same time. You can want to have a cock and not want to have a cock. You can be serious and silly, neither or both. We’re complicated and multiplicious. To quote the magnificent Julia Kristeva again, let’s try “to bring out – along with the singularity of each person and, even more, along with the multiplicity of every person’s possible identifications (with atoms stretching from the family to the stars) – the relativity of his/her symbolic as well as biological existence, according to the variation in his/her specific symbolic capacities.” Embrace it all, and love yourself.

And when you do something, maybe do it because you want to, because you’ll enjoy it. That’s often a rich and complex option, and not necessarily a selfish or easy one.

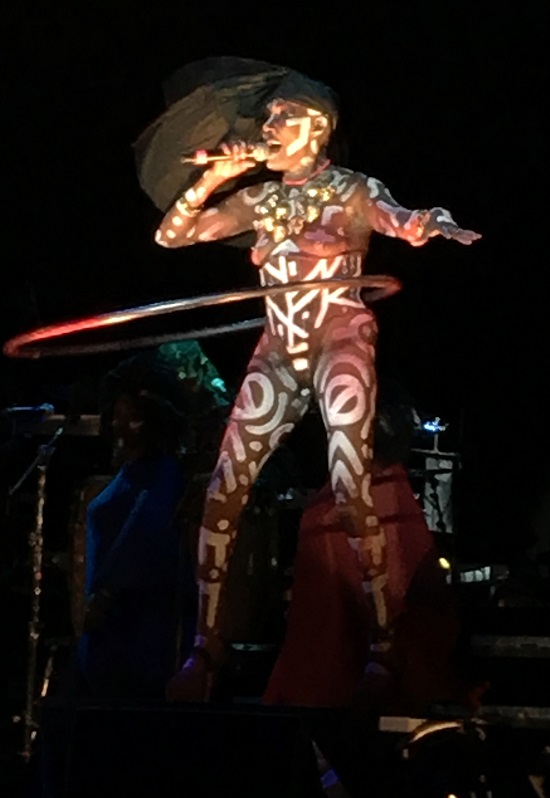

Grace Jones closes the festival, late on the Saturday night. She starts with ‘Nightclubbing’, with the pleasure of the bass, the visceral and unifying oomph-oomph power of that rhythm. In the lyrics is a proud statement of fact: “We’re what’s happening.” Jones is topless in a black corset, covered in a variation of that Keith-Haring-does-voodoo bodypaint with a leather fringe covering her face. During the two-hour set she variously wears a mane and a tail, a grass skirt, a strap-on, and a hat which is also a disco ball that illuminates the stage and the front of her rapturous crowd. She whips her naked male poledancer; she rides topless on the shoulders of a security guard like Lady Godiva, touching hands with the crowd. It is comic, daft, ace. She’s a bullfighter during ‘Libertango’, then a prowling beast, she is “feeling like a woman, looking like a man” during ‘Walking In The Rain’, and it is always strange strange strange. She shows the pleasure of being alone in a crowd, being strange among strangers, recognising your weirdness – and isn’t that part of the pleasure of popular music? We’re all pretending, together alone on the dancefloor.

It’s interesting too that two of the great songs on Nightclubbing, ‘Use Me’ and ‘Demolition Man’, were written by men and are wildly enriched by Jones’ adaptation. (Much as I love the Bill Withers original of ‘Use Me’. As for ‘Demolition Man’ and, indeed, Patti Smith’s ‘Gloria’, I like to imagine that they make Sting and Van Morrison feel grateful and vaguely cowed.)

Grace Jones is as glorious and as camp as can be. She’s got the artifice, the androgyny, the outlandishness, the theatricality, the sincerity, the fun, the filthy beautiful pleasure of it, the non-binary magic of it. “Camp taste turns its back on the good-bad axis of ordinary aesthetic judgement,” says Sontag. “It doesn’t argue that the good is bad, or the bad is good. What it does is to offer for art (and life) a different, supplementary set of standards…” Camp, you see, is non-binary. “Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation – not judgement.”

Grace Jones knows the power of fabulousness, how “we, who are thought less than, shall burn brighter than our oppressors”.

She knows about wanting a cock, too. Tonight for ‘My Jamaican Guy’ she wears a strap-on dildo in addition to her topless corset, and as she dances and lolls about on the stage the dildo dances and lolls about too. She is ridiculous and beautiful. She once said, while berating our sexist society, “I want to fuck every man in the ass at least once.” At least once. She is funny, and sharp, as well as playful and powerful. She is, as you know, the master and mistress of androgyny. She has also said, “I am my own sugar daddy. I have a very strong male side, which I developed to protect my female side. If I want a diamond necklace I can go and buy myself a diamond necklace.”

Like Christine & the Queens, Grace Jones is fun. She is strange and sexy and subversive and fun. Grace Jones is magnificent, androgynous, smiling, chatting, “feeling like a woman, looking like a man”, tits out, dildo on. There is an important contradiction here: age, gender and race seem irrelevant to a performer as fantastic as Jones (just as with Prince, her “appearance and agility laugh in the face of such banal facts”); but there is power in the fact that this is a 68-year-old black woman, tits out, smiling, powerful, happy, playing some of the greatest songs of the past 40 years on a headline festival slot in front of an adoring crowd. When we are still abusing and destroying people on the basis of their gender, race, sexuality or age then it is still politically vital to recognise those identities. But we can play with them too and maybe, eventually, they will cease to exist. Destroyed through play.

There are other facts that also seem banal in the face of Grace Jones, like the fact that she’s a genius. Of course she is, or she isn’t, who cares. Grace Jones makes me want to (in the words of Kristeva) “break the code, shatter the language, to find a discourse closer to the body of emotions, to the unnameable repressed by the social contract.”

She talks a lot, ad libbing daftly, between songs. There is a theatrical lack of artifice, and an understanding of life as theatre, of identity as performance. She is enjoying herself, she smiles, she is friendly and chatty and kind and polite, she loves being in Oslo, she loves us. She loves herself too, sings ‘Amazing Grace’ as a little interlude, and she knows she’s amazing. She knows that loving yourself can be a radical act, and fun. (Letissier has her own, tentative version when she sings “I am actually good” in Tilted.)

There is daftness and wonder during ‘Slave To The Rhythm’, her fabulous finale. She sings the whole thing while hula-hooping. “Never stop the action,” she is smiling, she is deadpan, she is smiling again. “Keep it up, keep it up. Work to the rhythm, live to the rhythm, love to the rhythm.” She is serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious. Susan Sontag would love it. Sometimes we get so worried about being right (and not so worried about being kind or happy) we put ideology before observation, theory before experience, righteousness before pleasure, social contract before first principles. Grace Jones doesn’t do that, Christine and the Queens don’t do that. They are having fun. To be subversive and radical and useful, we need to be having fun. How else are we going to keep it up, keep it up?