There’s nothing to be done about it, but I often wonder if cinema’s progress as a radical, avant-garde force was hampered by the introduction of the talkies. Prior to that, live cinema had the potential to be an audiovisual experience that went beyond the bounds of mere vocal dubbing, a potential only realised in programmes like this one, Electric Nights at the BFI. Damn you, Al Jolson.

It’s all about mis-timings. A century ago this year, the Futurist Luigi Russolo wrote his Art Of Noises manifesto. In line with the general programme of the Italian arts movement, he wished to smash the protective cloisters and sanctuaries of traditional art, ushering in a new aesthetic era of dynamism, inspired by the great social transformations wrought by the machine age. Noise was key to that. “Ancient life was all silence. In the nineteenth century, with the invention of the machine, Noise was born. Today, Noise triumphs and reigns supreme over the sensibility of men,” he wrote. “We find far more enjoyment in the combination of the noises of trams, backfiring motors, carriages and bawling crowds than in rehearsing, for example, the ‘Eroica’ or the ‘Pastoral’."

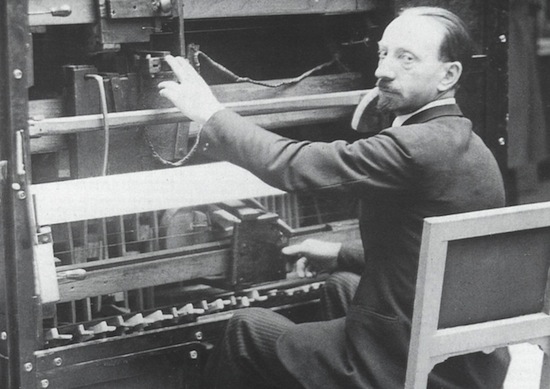

To this end, Russolo began work on what he called his “noise intonators”, large, cumbersome devices, which were capable of emitting a range of mechanically generated sounds imitative of every day life. These included “Roars, Explosions, Bangs, Booms, Whistling, Hissing, Muttering, Gurgling Screams, Shrieks, Wails, Hoots, Howls, Death rattles, Screeching, Creaking, Rustling, Buzzing, Crackling and Scraping.” They were, in effect, prototype synthesisers and properly, retrospectively revered as such by future generations of electronica innovators. They were even used at early cinematic performances, though their technical limitations made their sonic impact a little anti-climactic. The last of the intonators was destroyed by the Second World War, lost while on exhibition at a Parisian cinema. Little instrumental progress was made in the development of electronic music between 1913 and the introduction of magnetic tape after World War II. During this lengthy hiatus, talkies came into their own.

Electric Nights, a one-off event curated by the Noise Of Art collective’s Ben Osborne, sought to recreate the conditions ideally envisaged by Russolo, and the relationship he hoped to establish between noise and the art of cinema, fledgling in his own time. First up tonight is a series of short films of everyday life in Paris in Russolo’s own era. These scenes of market life or work on the Seine are naturally fascinating and vivid, in both how much and how little they have in common with every day life in Paris 100 years later. They also remind the viewer of the work of UK documentary film-making pioneers Mitchell & Kenyon. However, whereas their restored footage is shown nowadays with a wistful, mildly evocative chamber music soundtrack, for this show, Coldcut provide an accompaniment of sounds which capture the bustle, immediacy and atonality of city life, while Ben Osborne samples some of Russolo’s own sounds which have survived on recordings. This is undoubtedly what the great man would have wanted – he died in 1947, just before the birth of musique concrète.

Frost

The main feature is a new soundtrack to Vsevolod Pudovkin’s 1926 film Mother, based on a novel by Maxim Gorky. It’s a fine movie, though it probably belongs in the second rank of Russian revolutionary cinema, behind the great masterpieces of Sergei Eisenstein, whose montage methods it uses, though not to the same ingenious effect. Nonetheless, it packs a tremendous emotional clout, added to greatly by the contemporary, live soundtrack of Norwegians Aggie Peterson (Frost), Per Martinsen (Mental Overdrive) and the Russian Sergey Suokas (Slow). Set in 1905, the film tells the story of a family riven by a worker’s strike. The father is hired by the strike-breakers, his son is a revolutionary. When the father dies, the son is among those jailed on trumped up charges. The mother comes round to his support and in a stirring, albeit tragic climax, joins the revolutionaries, the epitome of the resolve of the Russian masses, whose uprising is symbolised by footage of the ice floes of winter broken up by the coming spring. The trio’s soundtrack is equal to the massive forces and themes which course through the film – tornadoes of micro-sound, a million tiny electric furies, during the strikebreaking scenes, great, heavy washes of melodic fragrance during the more poignant moments and pulse-quickening robotic beats as the film moves towards its final, armed confrontation. A perfect marriage of noises and silents.

David Stubbs sat at his MacBook yesterday

The Art Of Noises divided "noise-sound" into six groups:

ONE: Roars, Thunderings, Explosions, Hissing roars, Bangs, Booms

TWO: Whistling, Hissing, Puffing

THREE: Whispers, Murmurs, Mumbling, Muttering, Gurgling

FOUR: Noises obtained by beating on metals, woods, skins, stones, pottery, etc.

FIVE: Voices of animals and people, Shouts, Screams, Shrieks, Wails, Hoots, Howls, Death rattles, Sobs

SIX: Screeching, Creaking, Rustling, Buzzing, Crackling, Scraping