Photos by Natasha Bright

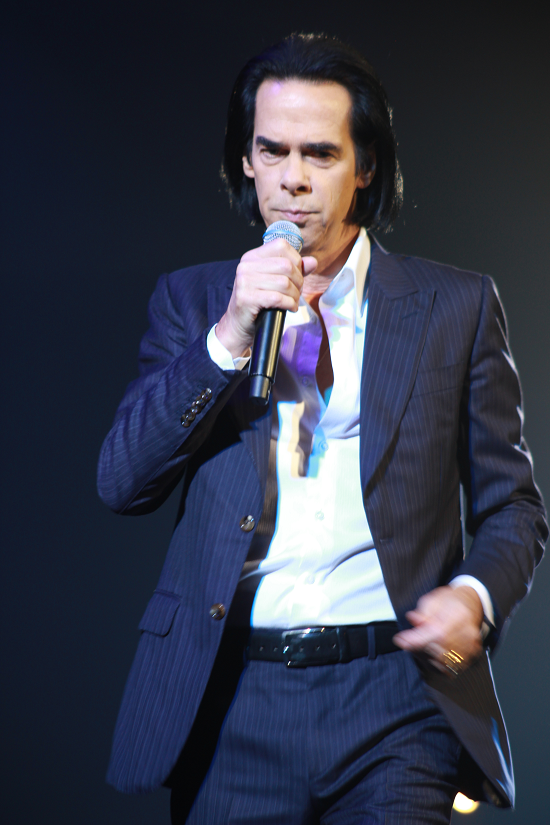

“He’s so fucking loveable,” coos Nick Cave in Bradford as he stares across the stage at Warren Ellis. More accolades soon come when Cave declares Ellis’ count-ins for songs “the most erotically-charged in rock n roll.” Ellis softly counts them in as Cave plays delicately on piano and a whir of immersive synthesiser slowly fills the room like a rising fog as the two glide into the dreamy and tender ‘Waiting For You’’.

Cave’s public affection for Ellis is longstanding; you only have to read The Red Hand Files to get a sense of their bond. “It is an extraordinary privilege to be around him,” Cave wrote in issue four of his newsletter. “When he is in full flight, he is unstoppable, and he is rarely not in full flight.” Or look to Andrew Dominik’s 2016 documentary One More Time With Feeling in which a grief-stricken and lost-looking Cave ponders, “What would I do without Warren? Look at him holding everything together.”

The pair’s collaborations have reached new levels in recent years since Ellis became a Bad Seed 25 years ago. In the mid-2000s he and Cave began scoring films together and this partnership recently culminated in a joint album, Carnage. While 2019’s Ghosteen may be a Bad Seeds album in name, it is heavily shaped by Cave and Ellis’ partnership, with Ellis’ micro Korg-shaped fingerprints all over it. Ultimately, Ellis’ creative role and influence in and around the world of Cave and the Bad Seeds has never felt more present and potent.

That said, for years “Nick Cave” has been used synonymously to describe the Bad Seeds’ output and he is frequently spoken about in wizardry god-like terms as an iconic songwriter. However, collaboration has always been at the essence of his success. As brilliant and bold a songwriter Cave is, he has always anchored himself to hugely talented collaborators at just the right time and many of them, as exemplified by his relationship with Ellis, have a deep romance attached to them.

Cave is a zealous romantic, it can be heard in his songs, his proudly uxorious words about his wife Susie (I’m fairly sure on stage her name dangles around his neck on a gold necklace), his deep love of poetry, his intoxicated fascination with the magic and mystery of the world, the people in it, and the potential God who sits above it all, and also in his creative relationships. Watching Cave and Ellis perform across three nights – Bradford, Manchester and Sheffield – with the smiles, nods, and subtle interactions, what you’re witnessing is not just two artists at the height of their collaborative powers but two men deeply in love with one another.

When Cave sings and performs, be it sitting at his piano, or out prowling and strutting the stage, he’s often doing so directly to Ellis as much as he is the audience – a spark igniting from their deeply locked eyes. During a rousing, bordering on transcendental, version of ‘Hand of God’ as Cave drops to his knees and the backing singers howl and Ellis shrieks like a crazed beast, there’s an exuberant joy to be seen amongst the demonic soundscapes that thunder and rattle from the stage. As Ellis yelps and violently convulses in his seat and Cave crawls on the stage spewing his lungs into the microphone, underneath the lacerating intensity it almost feels like children playing together on the floor.

Carnage and Ghosteen make up almost all of the set list and while the former is a record rooted in grief, which many will associate with pain and loss, when performed live they take on a quiet yet profound joy – songs that celebrate life and all it offers, where unimaginable pain and ecstatic joy sit side-by-side.

Ellis’ constantly droning synth, coupled with Cave’s sparse piano and ethereal vocal deliveries – elevated by backing vocals that range from deft to soaring – create a sort of half-lucid dreamland where nighttime lullabies and haunted nightmares occupy a shared space. In it Cave and Ellis form a sonic cocoon that expands enough to host the rest of the room. It’s rare the drums are featured but when they are – thoughtfully played with power and grace by multi-instrumentalist Johnny Hostile – it’s like a crack of thunder awakening you from a dream in the middle of the night.

Ellis and Cave slinking off on tour together – joined here by backing singers Wendi Rose, T Jae Cole and Janet Ramus – may be read as excluding the Bad Seeds or turning their backs on it, but in reality, they’ve obviously realised these slow, dense, hugely textual, and occasionally amorphous, songs may not land in an arena setting all that well. This smaller theatre tour is a place to release them into the world and let them float and breathe a little, rather than be sucked up into vast sonorous echoes of an arena before merging with the waft of hot dogs.

Plus, the fewer Bad Seeds you have on stage the less expectations there are for Bad Seeds songs and Bad Seeds material is scant. There’s almost an hour that goes by each night before anything pre-2019 is played: a bruised ‘I Need You’ that sees Cave turn the delivery of the song into mirroring last gasps of breath with genuinely moving intensity, quickly followed by T-Rex’s ‘Cosmic Dancer’ and ‘God Is In The House’, both backed by stunning violin work from Ellis.

When charting the evolution of Cave, Ellis and the Bad Seeds to where we currently are on this tour, you cannot overlook the importance of the pair’s soundtrack work. A truly pivotal moment is their score to Amy Berg’s West of Memphis documentary. The tones, moods and engulfing synths that permeate the film – as a result of Ellis experimenting with a micro Korg synth over his typical go-to stringed instruments – became something of a sonic template to some of Push the Sky Away, a late career breakthrough album that set them on the road from an academy to arena band.

Cave and Ellis’ cinematic worlds, and the way they work together in that capacity, has been crucial in shaping the last few Bad Seeds albums and a more experimental approach to song structure. “Soundtracks definitely set up some kind of working process,” Ellis told me a few years back. “Outside of the band experience you don’t have to make things in line with any rules. In film work you’re required to look at everything and consider anything possible. This came to me at a certain time in my life when I was looking for something more than just working within the constraints of a band. There was a freeing up of things and this fed back into the band. Each project keeps informing each other and it has helped set up a foundation for how Nick and I work that carries on to this day.”

However, Cave’s history is filled with such pivotal collaborative moments. Rowland S Howard’s frenetic yet deeply considered guitar work in the Birthday Party gave the band an unmatched intensity, ferocity and sonic framework and, for a period, he and Cave had a harmonious songwriting relationship. However, sharing lyrical responsibility became an issue and soon Cave’s eye was turned to another ghostly pale black-clad innovator.

One night while watching TV on tour, he saw a man performing with Einstürzende Neubauten on TV and fell for him, almost as though he was watching a film and became spellbound by a movie star. “He was the most beautiful man in the world,” Cave later wrote. “He stood there in a black leotard and black rubber pants, black rubber boots. Around his neck hung a thoroughly fucked guitar. His skin cleared to his bones, his skull was an utter disaster, scabbed and hacked and his eyes bulged out of their orbits like a blind man’s. And yet, the eyes stared at us as if to herald some divine visitation.” And so began a new creative partnership steeped in romance and adoration, as Bargeld became a central force in the Bad Seeds.

Cave doesn’t just work with people, he falls for them, often awestruck by a singular beauty he sees in them and wishes to extract. Both Anita Lane and PJ Harvey were also key creative forces and partnerships in Cave’s life that were romantic, albeit in a different and somewhat more physical sense. Cave fell for Harvey hard and of course wrote some of his best material in the aftermath on The Boatman’s Call. “I didn’t give up on PJ Harvey, PJ Harvey gave up on me,” he wrote in The Red Hand Files, before adding with a knowing wink, “I was so surprised I almost dropped my syringe.” Kylie Minogue may seem like something of an incongruity or anomaly in terms of Cave’s collaborations – 1996’s ‘Where The Wild Roses Go’ – but he has always held an undying love for Minogue and her work, remaining captivated by it for years, and frequently referencing it.

In his 1999 lecture ‘Secret Life Of The Love Song’, Cave aligned Minogue’s pop songs with the canonical love songs of Leonard Cohen, Tom Waits and Neil Young. “Occasionally a song comes along that hides behind its disposable, plastic beat a love lyric of truly devastating proportions,” he said of ‘Better The Devil You Know’. “It shows how even the most innocuous of love songs has the potential to hide terrible human truths. Like Prometheus chained to his rock, so that the eagle can eat his liver each night, Kylie becomes love’s sacrificial lamb bleating an earnest invitation to the drooling, ravenous wolf that he may devour her time and time again, all to a groovy techno beat.” Kylie Minogue was asked to feature on a murder ballad for a very good and specific reason – because Cave was already inspired by her approach and delivery of what he called “one of pop music’s most violent and distressing love lyrics.”

Perhaps Mick Harvey is the exception to the rule here, who despite being of immense importance to the sound and trajectory of the Bad Seeds, played a more organisational and, at times, managerial role, shifting the dynamic away from something that could ever be gushingly romantic. Cave has acknowledged the significance of these previous partnerships, writing in The Red Hand Files: “The Bad Seeds these days are on some level defined by a series of absences,” he says. “It is difficult for some to see the Bad Seeds without also seeing the spirits of Blixa Bargeld, with his terrifying, tortured guitar or Mick Harvey, with his vast musical intelligence and his steely, censorious eyebrow. These extraordinarily intense musical collaborations found their natural ends but, even so, are still woven into the cloth of the band. Dear Conway and his ramshackle piano, Barry Adamson or Kid Congo Powers, or the limitless creative spirit of Anita Lane, are all strangely present within their absence.” In 2007 Cave was placed in the Aria Hall of Fame but had to take it upon himself to induct his bandmates from across the years, as they had not been deemed worthy.

This isn’t to suggest Cave is some kind of vapid sponge who sucks up the goodness from everyone, absorbs it as his own, and moves onto another fleeting fancy but simply that the supposed genius of Cave is, if anything, a combined genius of many. And no more so does Cave seem to relish in this arrangement than with Ellis. They have struck a dynamic that is truly rare in music, a seemingly ego-free songwriting partnership that is so deeply rooted in love and trust that it allows them to enter a realm without limits and constantly come out with new and unexpected results. “We have developed a style of songwriting based almost exclusively on a kind of spiritual intuition and improvisation,” Cave has said. “That feels, as Henry Miller prescribes, calm, joyful and reckless. In the songwriting sessions we sit and focus and grin and crash around in things.”

They’ve managed to take this deeply intimate arrangement of focus, grinning and crashing around and bring it to the stage with that same spirit not only intact but transmogrified into something new. ‘White Elephant’ – a late period masterwork – epitomises this wonderfully, as it shifts from a menacing, brooding, gargling charge into a joyful gospel explosion. It’s a song that radiates fun and focus, tension and release, and ink-black humour with unashamed glee. It’s a piece of work that could only come from a quarter of a century of collaboration and friendship laying the groundwork for it to come out as unique as it is.

It’s refreshing to see two artists commit so passionately, obdurately, and without compromise, to new material with a back catalogue as rich as theirs to dip into at any point. An encore featuring ‘Henry Lee’ and ‘Into Your Arms’ may give the old guard fans a little taste but there’s a limit. In Sheffield, a shout for ‘Red Right Hand’ rings out. “We’re not playing that,” Cave quickly fires back. “Just go home and watch fucking Peaky Blinders if you want to hear that.” Instead, they plunge into the sprawling and engulfing 15-minute closing track from Ghosteen ‘Hollywood’, which quickly has the room transfixed in collective silence.