I came to extreme metal, or at least post-metal, sludge rock, or whatever experts in branding would describe Neurosis’s music as, late in life. I had been listening to music which sounded a bit like metal for years (Godflesh, Black Flag) and other groups that nearly were (ACDC, Sabbath), but touching the actual shore of the genre, far less travelling to its absolute heart of darkness, eluded me.

Looking back, the fundamentally tribal musical era, and atmosphere, I grew up in demanded that one chose sides in a way that might be considered absurdly self-limiting today, and if there were adolescents that lived metal, rejecting their look, rituals and war dances, preceded giving their music my unbiased consideration. Truth resided in appearance, and whatever lay behind that was stigmatised accordingly, especially when other surfaces had so much to offer.

So what changed in mid-life? Moving to the countryside, the deep resemblance of days to one another, barren views that appear to be waiting for you, immersion in things replacing swift responses to them – these all helped. Time also changed the way I expressed the same preferences and the form in which I looked for them. My mute incomprehension towards music like Neurosis’ became an incomprehension in the face of new experiences which their music slowly started to reflect, and metal, especially in its least filtered form, eventually began to make sense to me.

The search for a new musical vocabulary, or enlarging an existing one, had in the past struck me as too aspirational a way to embrace what must come as the result of instinct. Yet something like it had already occurred once before when I found that classical music, in my early twenties, spoke to some version of myself I had not yet become, the experience of listening to it the anticipation of a future sensibility it would take years to completely attain. Extreme metal, conversely, reminded me of a person I had been and a way of understanding experience I had never fully acknowledged; bluntly, painfully and sometimes fearfully, this recognition the ultimate fulfilment of experiences I had been unwilling to complete, or completely acknowledge.

Far from making me want want to head-bang, listening to Neurosis is a strangely passive activity, and though it is not the kind of music many listeners would like to wash over them, its severe tide can be paradoxically relaxing. This is music drawn from the grim accumulation of intense experience, from unresolved emotions that sound like they could bring the building down, while requiring you to stay still and allow it to happen, as this is a danger you do not want to get out of the way of. It is not without antecedents, as their live version of Joy Divisions’s ‘Day Of The Lords’ testifies, but Neurosis’s concentrated and stately probing of these areas, often sounding like text book definitions of harrowing gloom, have an unhurried quality common to those who believe they have all eternity to make their point. This requires patience from the listener, who might prefer a similar message to be made faster, and faith that the slow emergence of qualities can be as rewarding as what is immediately arresting. And that, in turn, requires a sense of balance that I previously listened to music to eclipse and obscure, believing it to be the domain of the very dull.

Interwoven with their shock and awe and volume, is a carefully controlled musical language that is perhaps more likely to be understood at forty as make sense at fourteen. I am indebted to Laina Dawes insights in this direction, for she has written brilliantly on how Neurosis’ songs of damage and introspection sung loudly and openly, are powered by a courage that loses nothing by admissions of vulnerability, subverting traditional misconceptions of both masculinity and the genre. The sense of knowing what you are, for better or for worse, bleeds off the music, as does the death of need; need for approval or un-constructive compromise. An adolescent version of these qualities, not caring what anyone thinks of you, is often based on an ignorance of what comes next. This produces great art, much of the foundational work of rock and roll in fact, but sounds qualitatively different to a music that understands the consequences and effects of its decisions. And the fact that Neurosis have actually made a pact that they will play together until they die, the ultimate declarative promise, is a similarly bold disavowal of the kind of careerism we are all now inured to, having watched so many acts reform for reasons other than total compulsion.

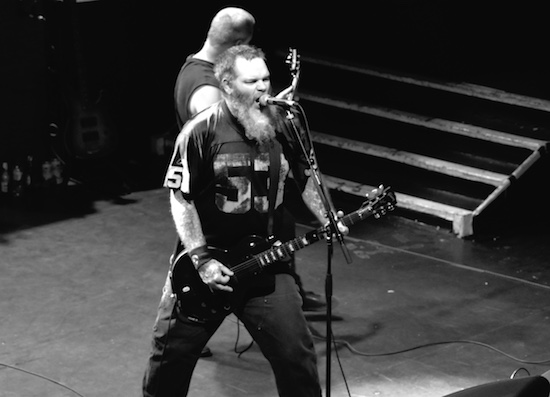

With this absence of pretentiousness combined with an utter fearlessness, Neurosis look like they could be their own road crew, and an aversion to theatrics, elfin myth and spandex, make watching them easy on a initiate who may have feared the worst from a live metal show (having never been to one). The sheer attack of it is exhilarating, and the vocal back and forth between Scott Kelly and Steve Von Till, shouting like two tank commanders trying to be heard over a battle, (Dave Edwardson, the bassist, is their secret weapon, dropping growling vocal bombs) is unexpectedly joyous, given the nature of the material and its forceful delivery.

On record Neurosis demonstrate extraordinary range (from ambient and folk metal to their punk/hardcore origins), which isn’t always as obvious watching them live, but if some of their sonic subtlety is lost in the assault which tends to rely more on impact than textures, it is worth remembering that nuances are often best grasped in private, and the show would be unlikely to have the same cathartic or therapeutic effect if it was all details.

The ten tracks they unleash at Koko span their entire career, showing off their taste for musical contrast (each song is fast and slow, loud and quiet, harsh and gentle, punk and prog), yet lose nothing to incoherence, their performance a hard-learned lesson shared with generous jouissance that nonetheless brings the listener up short. The gaps between songs sound like they are there to give the demons time to recover, the curiously long intervals between them filled with what sounds like an orchestra trying to tune up, or at least not fall off stage, the synth projecting an eerie and cheerful ambience, before hostilities re-commence again.

It may be a reflection of the average age of audiences for a band who are celebrating their thirtieth anniversary, but the group do most of the physical work tonight, the crowd enthralled and attentive though largely subdued in a kind of hypnotic awe. The centrepiece of the set is ‘Broken Ground’, the highlight of their recent album, Fires Within Fires. This haunting confession starts a little like a Springsteen country(ish) ballad, tentatively, "we seek the sun in endless night and burn in its forbidden light", before proceeding loudly on its knees towards the same light that will ultimately incinerate it. As all hell breaks loose, what is latent all night becomes un-ignorable; that pain expressed this directly and honestly is redemptive, whether the light referenced is a chimeric illusion or necessary truth, and the ability to live with this gargantuan capacity to suffer is the musical upshot of being made stronger by what has not killed you. Watching the group perform the night before Trump’s election victory, and listening to them again a week later as I tried to write this review encapsulates what Neurosis offer mid-life perfectly: what we lack in light and hope, we may yet make up for in the strength and resolve to simply go on. These songs of engagement and endurance, the maturity of which is easy to deride as the rock & roll equivalent of responsibility, will in all likelihood be a more politically and musically satisfying response to these dark times than the gesture heavy escapism I once mistook their battling example for.