With the possible exception of the Lady Gagas and Beyonces of this world, the switch-offable yappy figures that pass as pop stars today have been wholly eclipsed by the onset of the celebrity chef. Gordon Ramsey = John Lydon, Jamie Oliver = Paul Weller, Nigella Lawson = Siouxsie Sioux (to Sophie Dahl’s Toyah). Ramsey in particular has infiltrated the US like no British group could these days with his Kitchen Nightmares. It’s indicative of the fact that over the past couple of decades food culture has changed beyond recognition as the music industry has declined.

It’s partly for this reason I found myself at a gig-stroke-supper club at Cafe Oto, Dalston, in the form of Matthew Herbert’s One Pig, Dead and Alive event, a live action installment of his One Pig project. The point, it seemed, was to tackle further the issues raised by the One Pig album which is currently mixing it up in many an end of year list. It charted the brief life-cycle of a dinner table-bound pig. In a way it rebranded industrial music – for here was the food industry in action, pink life reduced to grinding monotony, its destiny made abundantly clear from the outset with the careful slicing of sampled oinks and squeals, turning them into ever-more repetitive rhythms.

The talk chaired by food writer Tim Hayward that preceded the performance and dinner was revelatory. Did you know that each of us comes into contact with pig around twenty times a day? “It’s in lipstick, it’s in train brakes, it’s in margarine, it’s in bullets – not that anyone here will use bullets today,” said Herbert.

Next to the grinning foodies, Herbert was the stern-faced cynic-in-residence. At each optimistic prediction about how food culture in the UK might be wrestled out of the supermarkets’ tight grip he had his hand over mouth, or stroked his chin in disagreement. “During this period the supermarkets’ power has consolidated. The government has handed control to the supermarkets and the decisions are made on price alone.”

Herbert’s musical horizons, on the other hand, have broadened. Digital advancements in music have been a revelation. Music, he said, “isn’t just about something. It can be that something”. He talked of emulating the great symphonies of the 19th and 20th centuries, which “engage with the big struggles about life and death” and “to give a voice to an otherwise anonymous animal in the food chain. The initial starting point is the fact that it is a life”.

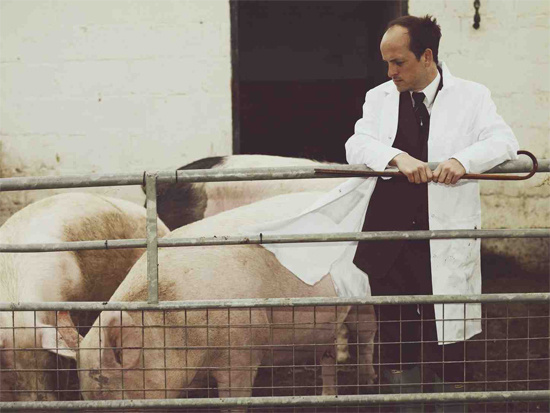

The food was provided by the local pop up dining company, Shacklewell Nights, who served up pork rilletes as we waited for Herbet and his musicians, dressed in the clinical abattoir dress of white lab coats, to prepare. The set up was a weirdly comic play on the pig’s predicament. Up the front, behind the StyHarp – an electric fence of wires attached to samples and gadgets – was its inventory, Yann Seznec, bouncing up and down pulling at the strings.

He changed lab coats as the band moved on to the next song that represented the month of the pig’s short life, the name of the month written on the back so we knew where we were. August was calm and serene. October was languid and optimistic, with the suggestion of a grim future. December was maudlin but funny at the same time, like a kind of fairground nightmare. In January, it died and we were treated to low gravelly noises, presumably from the pig, and, in February, the sawing of a pig’s trotter. The audience, who had forked out £57 each for the pleasure, looked uncomfortable. The sawing was sampled and repeated as a chef fried a pig on stage, which was sampled too. And it smelled delicious!

It’s not every day you can say a sample had you literally salivating, or that you tapped your foot to the beat of a drum made out of a pig who died on the same farm as the one you were about to eat the delicious loin of. It is perhaps this kind of bravado that irked PETA, who attacked Herbert in March for thinking “cruelty is entertainment”. It seems a slightly wrongheaded attack now. The performance and dinner made me think about the way the meat I consume has been treated more than anything else has ever managed.

“At this time of year I take my happiness and disappear,” sang Herbert in the closing moments. It is a lyric that comes from the album that came out in October, but is one that pretty much describes the Christmas experience – this time of willed amnesia and collective food coma that is protected by the shell of merriment. It haunted the meat aisle during a pre-Christmas supermarket visit. Metallic trolleys clanged together as pale-faced couples casually swore at one another over which plastic-packaged greying lump might be best for Boxing Day. Only, they didn’t look very happy.