“I stand in front of you. I’ll take the force of the blow. Protection." – Massive Attack (1994)

A few weeks after the November attacks in Paris, I started having violent dreams. I’d be trapped in situations and wouldn’t be able to get out as untold terrors unfolded. I went to see the doctor for something else entirely, but I decided to share the fact I was having nightmares with him at the conclusion of our consultation. He referred me to a psychologist straight away. At first I protested – after all, <a href=“http://thequietus.com/articles/19226-paris-terror-attack-friday-13″>what I’d experienced on the night of November 13th was nothing like as horrendous as that endured by hundreds of people, and the hundreds and thousands who’ve been dealing with the horrific ramifications ever since. My doctor’s practice is based in the 11th Arrondissement, a three minute walk from the Bataclan, and he told me the surgery had been inundated with traumatised patients from the local area following the attacks. He also told me I might be suffering from Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

The NHS website says that “someone with PTSD may be very anxious and find it difficult to relax. They may be constantly aware of threats and easily startled. This state of mind is known as hyperarousal." I certainly felt like a fraud sat in the waiting room before meeting with the psychologist, but just being in an enclosed public space like a waiting room made me feel uneasy, even if I knew I was being irrational. A woman, also waiting, started freaking out about an abandoned grocery trolley in the hallway. Another man, waiting in the crowded salle d’attente, sheepishly put his hand up to confirm ownership of said trolley. She marched out, visibly shaken, and perched herself on a ledge in the hall with her head in her hands.

I was prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, and during our next few meetings the consultation would take on a familiar pattern. I would talk for a while, then the shrink would say something profound, albeit bordering on platitudinous, then he’d up my meds by 5mg. While he and his dark arts appeared inadequate, his methods may have been more effective than I gave them credit for, or maybe time had its part to play. For whatever reason, after two or three months the bad dreams stopped.

I also ceased checking the listings for incendiary band names, as ridiculous as that sounds. This was surely the most irrational manifestation of fear, where I’d ruminate on a group’s moniker to determine how offensive it might be to Islamic terror groups before deciding whether to go to the show or not. The name Eagles of Death Metal had seemed almost too perfect not to have been chosen specifically for the attack on November 13th; that was before I discovered there’d been a history of threats on the Bataclan from extremists. Nonetheless, a week after the massacre at the venue, hacktivists Anonymous claimed ISIS were planning a hit on a Five Finger Death Punch gig in Milan. The show was postponed as a precautionary measure. As a result I started avoiding shows where death or disaster might be alluded to in the band title, and while again it seemed irrational, there was still an element of what if. Trying to second guess the motives of terrorists is foolhardy, and follow it to its logical conclusion and you’ll never go out again. That doesn’t stop you thinking about it though. The fact 90 people were murdered for simply attending a rock concert at the Bataclan was entirely preposterous in itself.

I eventually quit making excuses about going to gigs, and I stopped leaving shows early or positioning myself near the exit in case armed intruders suddenly burst through the double doors. Sometimes I’d even get on public transport or sit with a coffee on a terrasse and not think about any imminent threat.

In May <a href= “https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/may/29/music-fans-target-uk-terror-attack-security-chief-glastonbury”>The Guardian published an article claiming a top counter-terrorism officer had told music executives to take extra security measures in the run-up to festival season. “Music fans and nightclubbers could be the target of the next major terrorist attack in Britain, a top counter-terrorism officer has warned ahead of the country’s festival season" read the piece. In France the threat has never gone away, and logic dictates that an attack could happen across the Channel too. Paris has been specifically targeted as “the capital of prostitution and obscenity" after all. Ironic, as Paris’ days of hedonistic notoriety are undoubtedly part of its illustrious history, but it’s hardly the epitome of a party city anymore (which is one of the reasons I like living there). No matter, my fears of being a legitimate target started again. We went to the We Love Green festival at the Parc de Vincennes in June and the lack of security made us feel wholly exposed and nervous. We stayed, because going home would be silly wouldn’t it?

The lineup for Rock en Seine was announced, and one of the names that stood out was Massive Attack, for several reasons. I wanted to be there, but I also carried a deep-seated fear of a cell of terrorists coming over the hill armed with kalashnikovs. Assailing a show by a band called Massive Attack would maximise publicity for those seeking infamy, or so my baked logic went. I figured the only way to deal with this anxiety was to draw upon the CBT I’d learned, and banish these obsessive thoughts by confronting them head on. I made a resolution to go out more.

On July 14th, 86 people were killed and more than 300 injured when a truck was deliberately driven along the Promenade des Anglais in Nice as people celebrated Bastille Day. France was in shock again, but the sense of déjà vu rendered many numb rather than surprised. As depressing as events were, Paris, nearly 600 miles away by road, continued functioning as per usual. On the evening of the 16th, two days later, I went to see DJ Shadow in a forest in eastern Paris. On arrival I noticed armed police lined all along the perimeter. Their presence was jarring. A month later I went to La Route du Rock in Brittany, a brilliantly run mid-sized festival a short drive away from the picturesque seaside town of Saint Malo. This time there was a large army presence. By now I was starting to get used to this, and if anything it made me feel more secure.

Rock en Seine this year has the kind of security reserved for a state visit. As we make our way to the Domaine National De Saint-Cloud venue, armed gendarmerie are waiting behind trees and situated at both ends of the Pont de Sèvres. It emerged in January that a French computer operator arrested on returning from Raqqa in Syria had told police that Abdelhamid Abaaoud – the ringleader behind the November attacks in Paris – was planning to hit a music event in the city. While it was impossible to pinpoint the specific date or location, spooked security services believed Rock en Seine might be the intended target, according to France 24.

And so a 40,000 Parisians get to see Massive Attack, safe in the knowledge that the French State is doing all it can to keep its citizens safe while they have a good time. Providing a good time isn’t really Massive Attack’s raison d’etre though. Horace Andy belts out the familiar first lines to ‘Hymn Of The Big Wheel’ and a large cheer goes up, but crowd int5eraction is not 3D or Daddy G’s objective. Words filter through the giant electronic billboards positioned behind them, and the atmosphere is strangely educatory. Eruptions of applause will henceforth be rare, the crowd stood more like they’re in assembly than at a rock concert.

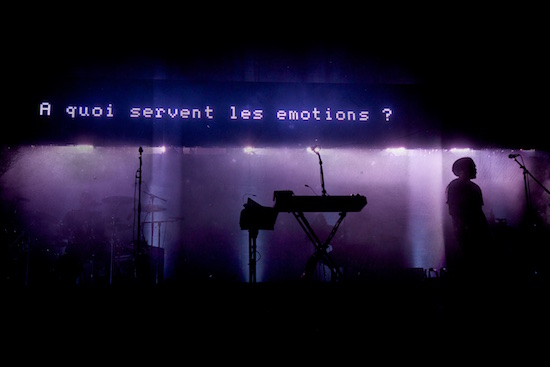

Questions appear on the screen and, translated into French, makes it all the more existential.

“Ou êtes vous maintenant?" (where are you now?).

“Quel est le but de mourir?" (What’s the purpose of dying?)

“Je ne sais pas," comes the answer.

The ante is upped on the projection for ‘United Snakes’, and you suspect the intention is a didactic one. Political parties flash and mash together, mixed up with sections of logo (they might be from parties or banks, it’s hard to tell). UKIP, Sinn Fein, Plaid Cymru, The Liberal Democrats, The Conservative Party… as the song unfolds, party names are prefixed with “jerk" and “evil" and other such pejoratives. It must be pretty deep because in front of me an alternative looking guy hands a spliff to a banker type, and I’m assuming they didn’t come together. There’s a sense that this is didactic in the sense that Banksy is didactic, making people feel clever by pointing out the obvious.

The multimedia experience should be immersive, and yet there’s almost a disconnect between what’s going on on stage and what’s going on behind. The lack of cohesion comes from the fact that what’s happening on the screen at any given moment is more interesting than the show itself. During ‘Girl I Love You’, a series of well-known names – some better known than others – glimmer from the stage in quick succession; Karl Marx, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Rachel Weisz, Ben Elton, Baron Lou Grade. Initially you wonder if the connection is Jewishness, though Mona Hatoum, Marlene Dietrich, Alek Wek and Freddie Mercury ensure you realise they’re all immigrants.

The best received moment is during ‘Inertia Creeps’ when among flashing newspaper headlines projected against the mise-en-scène is one about the burkini ban, a national embarrassment on a similar scale to Brexit, being overturned by the courts.

Speaking of England’s shame, Del Naja talks about “standing together with what we still see as Europe" ahead of ‘Eurochild’, and it’s during that song that the most poignant message appears above the musicians:

"Je suis Paris. Je suis Orlando. Je suis Bruxelles. Je suis Bagdad. Je suis Nice. Je suis Kaboul."

And then, “Nous Sommes Tous Dans Le Même Bateau."

We are all in the same boat.

The future is uncertain for all of us, and the likelihood of another terror attack is less about if than when. Antidepressants and meditation and CBT can help alleviate the anxiety, but won’t stop the wheels of history. I envisage a future full of risk assessment, of hoping it won’t be you or your partner or anyone you know caught up in it; of telling yourself there’s more chance of getting knocked over in the street or falling off a horse. But living in fear is what they want apparently, so you must set yourself free somehow.

The Massive Attack show almost feels like a work in progress, because there can be no resolution right now, and our future is like that too. All you can do is dance into the night and try to forget about it. Worse things happen at sea. Being at a festival surrounded by security forces is a sight we’ve had to get used to in France this past year. It might not be long before that’s the case across the rest of Europe too.