An accusation often – too often – leveled at contemporary music, particularly that which counts itself as part of the sonic “mainstream,” is its lack of overt political intent: the youth of today are “apathetic” and “disengaged,” even “narcissistic.” But nothing in this current climate is apolitical – even if it protests to be. Space is political; absentia is political; the Self is political, both in body and in mind. The truth, whether we like it or not – whether it tallies with your own (political) views in deciding where to apportion the blame for our current sorry state of affairs – is that, in 2016, there is no escaping politics. Even to say “enough is enough,” and willfully disengage is in itself undoubtedly a political act.

It’s prescient, then, to arrive in Iceland on November 2nd: almost exactly a week between the country’s own parliamentary elections and the climax of a presidential race in the United States that had begun to feel as though it might never come to an end.

While, by this point in time, the fact that Iceland is a country of extraordinary beauty is something like common knowledge, the landscape, unchanging for the most part, still never disappoints. Its expansive flats of volcanic remnant, daubed in a thick carpet of verdigris-like moss are both familiar and alien, its mountains – seemingly greener, blacker, or bluer than those found elsewhere, their hues differing from peak to peak – both impose and impress themselves in equal measure. But being here at this precise moment is a reminder that Iceland, whatever else it is, is no utopia. This is a country caught up in the same struggles that permeate worldwide – a little over a week ago, women in Reykjavík walked out of their workplaces at 2.38pm to protest the gender pay gap, and a few short days later the country as a whole decided against electing the Far-Left Pirate Party to power in the world’s oldest parliament. Against this backdrop, Iceland Airwaves – a now world-renowned city festival that sprawls for five days across the grid of the capital – manages to be a welcome break from, a counterpoint to, and a timely reminder of all of this.

With more women (marquee names like Björk and PJ Harvey and emerging artists more than worth your time like Ayia and dj. flugvél og geimskip, as well as the many, many, projects of Jófríður Ákadóttir) on the bill than most festivals combined and the hundreds of off-venue shows agreeing, after a collective intervention by musicians, to compensate those who play in their spaces, Airwaves this year – perhaps more than any other – is a statement of intent politically as much as musically. Over the course of these five days, like all statements it inevitably proves to have its flaws, but there are no utopias: to judge what happens in Iceland by some higher moral code is not only unfair but condescending – and this is a festival which should be commended for, both, being reflective of and reacting against its immediate reality.

Across the off-venue program – which includes the usual bars and cafes as well as the less conventional clothing stores, restaurants, art galleries, and swimming pools – and the main events at Harpa concert hall and the other mainstay Reykjavík venues, Icelandic hip-hop is placed front and centre after a swell of media interest since last year. With Kano and Dizzee Rascal also appearing over the course of the festival, GKR’s performance on i-D’s stage on Wednesday night makes for an interesting measure of exactly where the artform is at right now in the Reykjavík scene.

Adorned with a brightly-coloured hoody sporting his name and powered by a kind of youthful exuberance that can neither be taught nor properly faked, it’s worth noting that on one of his most popular tracks GKR raps about breakfast. Once more: GKR raps about breakfast. That’s not a euphemism either – we’re talking about cereal, about the first (and, if you’ll permit me, worst) meal of the day. It’s a far cry from Kano’s smoldering tribute/eulogy to the memory and reality of London’s East End, but in 2016 even Cheerios aren’t free from politics: this celebration of the minutiae of everyday life could easily be seen as a way of avoiding addressing what you might call “real issues,” but it’s painted here – in the confident brush strokes of GKR’s extroverted flow – as joy in the face of abject horror. Not in ignorance of the world but in spite of it. Between the relentlessness of work and the horror of the 24-hour news cycle, now more than ever there are demands on our time and our thoughts that have no truck with the idea of setting aside moments of the day as sacred space for decompression. And, yes, on one level – rushing around the stage, a pogoing neon blur – GKR’s music is a form of juvenile escapism, but a dedication to celebrating those moments of lightness is a heartwarming thing to watch. And it’s one that’s hard not to be swept up by in a room clearly absorbed by the spectacle.

In contrast, a few days later, GAIKA plays to a dark room – barely two-thirds full – his delivery often palpably anguished and confrontational, the gloaming of the beats and the darkling ambience of the electronics combining into something almost three-dimensional.

Like Atreyu dragging his horse through the swamp, GAIKA’s music shows not only an awareness of reality at its most disconcerting – his own predicament, geographically, racially, personally, and the present mire of events and attitudes worldwide – but also a refusal to accept that this is the way it has to be. It’s provocative and absorbing without needing the lurid visuals that help weave GKR’s universe together – both imminent and distant, it compels connection even as it pulls away in righteous self-preservation. Technical issues and a relatively subdued reaction from the crowd are rarely things to write home about with positivity, but as GAIKA moves about the stage, struggles with his microphone, and does his utmost to draw a response from the room, there’s a certain Sisyphean quality which feels more than apt.

In his review for the Reykjavík Grapevine, John Rogers, who stands next to me as this all unfolds, will later write that he "felt like someone should have frogmarched in the young rappers of Iceland to see a master at work." And, while it’s undoubtedly true that a great many of them would benefit from seeing just how much can be accomplished without theatrics and eccentricities – by just putting yourself on the line for half an hour – it’s also true that these are two sides of the same coin, albeit wildly different ones that may well never quite understand where the other is coming from. In 2016, after all, there’s no escaping the fact that we’re all coins recklessly tossed into the air or jangling in the pocket of one ideologue or other, nuzzling their junk involuntarily.

(It’s true, too, as he says, that GAIKA "won the room over completely." Sisyphus can suck it.)

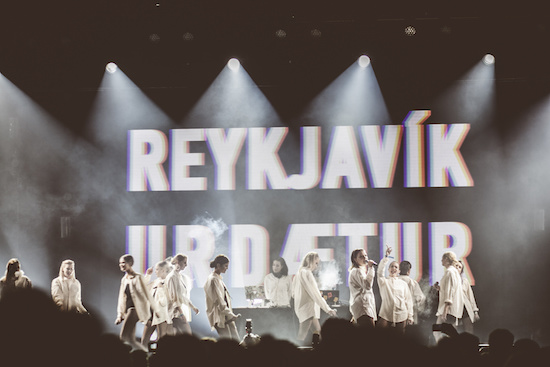

While the hip-hop scene may be a little homogenous in the pigment stakes – there’s a less than diverse national gene pool to thank for that – true to Airwaves 2016 form, the women of Reykjavík at least are represented. If, to return to a metaphor, GAIKA and GKR are opposing sides of the same coin (two facades of a single entity, never touching) then the ever-powerful Reykjavíkurdætur are the kind of act connecting the two.

Righteous and riotous in equal measure, they’re a revolving and evolving feminist rap collective that must now number close to 20 members. With ferocity that, while notable, doesn’t come close to GAIKA’s, and without any of his powerful subtlety, and packing GKR’s ebullience – sans the luminous escapism – Reykjavíkurdætur are a full frontal assault on gender inequality and the concept of sexual shame. With so many bodies on stage, the overarching message is always clear enough but its intricacies are sometimes lost and, as a result, so is its potency.

But rap isn’t the only thing on the menu, and elsewhere – removed from the hip-hop milieu – in a too-full, too-hot upstairs bar, Dream Wife are following the opposite arc. A three-piece UK/Iceland crossover band, Dream Wife are in the rare position of being in ascendancy both in terms of brutality and musical competence: skilled yet still undeniably savage, their particular brand of punk-tinged power pop is notably more power than pop, giving no fucks and fucking things up without bias. It’s refreshing, too, to watch a band so clearly invested in what they’re doing care so little about how others might perceive them: these are politics of defiance and of self-preservation manifest.

And it’s a performance in sharp contrast with the one which GANGLY – probably Iceland’s only trap supergroup, made up of members from mainstays Samaris, Sin Fang, and Oyama – deliver in the ornate surroundings of Gamla Bíó: their music is reserved yet expansive, the pitched-down shimmer just failing to conceal an undertow of looming threat. And while it’s true that the band and their drum-punctuated haze are a prime target for the kind of person who asks "Where’s the drop?" without irony, the slow burn creeping dread of a performance almost entirely on one level is far more disconcerting. It’s also far more true to life: as a civilisation we’re always waiting for the next catastrophe – even as things change day by day, incrementally, barely perceptible – the storm always on the horizon, all the while soaked through by a light but constant rain.

As well as being the first year that hip-hop has really been given room to breathe across the festival, other than in scattered off-venue performances and with the exception of Skepta‘s microclimate-generating outlier performance at Reykjavik Art Museum last year, it’s also the first year that the throng of people – entering, exiting, or standing around looking exasperated in the main venues – hasn’t resembled a hideous yet captivating Bosch painting. Things still aren’t perfect, there’s a real sense of community to the smaller, more ad-hoc shows, but not so much at the separately ticketed ones or anything at Valshöllin (an arena-cum-sports hall type venue with no real place in the festival other than as something for people to complain about en masse or a reason to spend nine hours in the more relaxed climes of Kaffibarinn). There’s a worrying dearth of electronic music, too, which – we find out over the course of the week, as we try and fail to find some decent house or techno – is representative of a wider vacuum in the Reyjavík music scene. And though it certainly isn’t up to Airwaves to create the artists needed to plug that hole, we should expect them to be actively seeking rather than waiting.

But, while we can always hope, we shouldn’t expect perfection anyway: this festival is run by human beings, for other human beings, and will always have its limitations and its failings as we all do – from the whims of Capitalism to the technical realities that forced Ben Frost to cancel a much-anticipated second performance. There are no utopias, and pedestals are inevitably poorly balanced, but facing up to those flaws, taking responsibility for the everyday politics, and pushing for change – not seismic change, but noticeable progress – makes Airwaves a credit to the festival circuit beyond the highlights of its ever-expanding program.