Like many a berserk idea, this one was born of alcohol and summer air. On the first Tuesday in August, at a wooden table outside a pub on an untypically quiet Islington street in the north-western quadrant of the Holloway Road, Frank Turner is being forced to account for himself.

The person doing this forcing is me.

As a working music journalist, it is not my business to be anything more than friendly with the artists and bands about whom I write. But there are exceptions to every rule, and Frank is mine. He is the ‘kind’ of performer that The Quietus rarely profiles; more than this, there have been occasions when this site has driven its passenger-packed bus all the way across town in order to run him over. Given this, it is at this point that I reveal my own personal investment in this story in order that I might give the viewer the opportunity to change the channel before the opening credits have finished flashing upon the screen.

But I do so without apology.

Where we were we… right, of course, outside the pub: summer sun bidding the day goodnight; six people, only two of whom work in ‘the industry’, talking about things other than the music business; conversation clattering about the place like a rodeo in the kitchens of the Regency-Hyatt. Pints of beer and, crucially, large measures of whisky are raised full and lowered empty.

The question that propels this story into life comes from me, and it is not the first time it has been asked.

“Frank, why have you never played Barnsley?”

“I’m playing Yeovil,” comes the apples-and-spaceships answer.

“Yeah, but not Barnsley.”

“I’m playing Blackburn,” is his next witness for the defence, called not because all northern towns beginning with ‘B’ (and there are dozens of them) are the same to southern eyes – as is often the case – but because they are places of equivalent size and type. Also, they are both the kind of towns at which artists whose names are printed in the national press do not appear.

“I ask you,” he asks, not unreasonably, “who else would play Blackburn?”

“But Frank,” I say, as if speaking to a child, “you’re kind of making my point for me.”

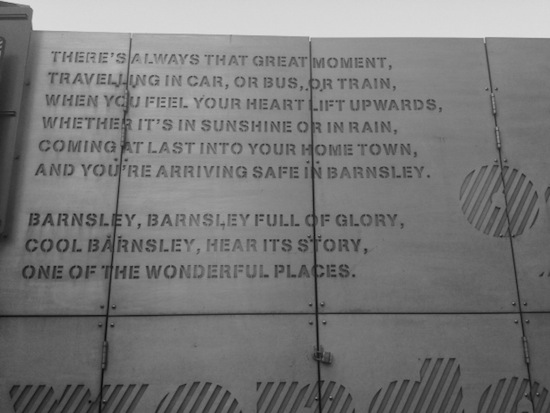

It is, to me, an important point. Despite not having lived there for more than half of my life – “I know all about northerners,” I tell my family. “I used to be one” – Barnsley is my place of birth. The town itself [‘Tarn, where I’m from] has a population of more than 80,000 people; the Metropolitan Borough of Barnsley – essentially a satellite ring of erstwhile coal-mining villages – is home to almost 232,000 residents. It is the administrative capital of the Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire. Yet aside from the Arctic Monkeys, who were formed just 10 miles north in Hillsborough (and whose frontman, Alex Turner, attended college in Barnsley) no one plays there.

Not even Biffy Clyro, who once set up their backline at the Stornaway Sea Angling Club, or Frank Turner, who happily performed on a barge to an audience of eight people and takes justifiable pride in bringing his £5000 guitar (which he received as an endorsement) and his universal charms to the kind of places other artists of a similar commercial standing would never think of visiting.

In a northern-lite accent, and with a measured slur, this information is laid at the musician’s ears. He’s heard it before, and knows, surely, that he will hear it again. We’re also, by now, a couple-three more drinks down the line.

The two hands with which he earns his living hit the wooden table with some emphasis.

“Alright,” he says. Then he says it with a smile.

“Alright. If you can find me a venue, I will play Barnsley. I am free from a fortnight on Monday, for that week. I’ll do it for the price of my train fare and free drinks on the night.”

There follows a lightning-strike of silence.

“Alright?”

“Seriously?”

“Seriously.”

On ‘Try This At Home’, a song from 2009’s Poetry Of The Deed album, his third, Frank Turner sang that “the only thing that punk rock should ever really mean, is not sitting ‘round and waiting for the lights to go green.” With a Neil Peart drum-solo clattering around my head, on the morning of Wednesday August 6th I took this advice to hand: Mission Implausible was Go.

I chose to work quickly, and to brick-up all avenues of equivocation and escape. I knew that while Frank himself would not renege on a promise made at an hour that saw his eyes pointing in slightly different directions, there were other factors to consider. Little things like the fact that he is signed to a major label. That he has professional management (an organisation that indulged this folly with uncommon good grace). That he has both a booking agent and a promoter. That the plan was to put him onstage in a pub or club, when in fact his commercial profile is of a size sufficient to fill every seat in South Riding’s largest indoor space, the Sheffield Motorpoint Arena.

The matter of accommodation was simple; we would be ‘stopping’ at my mum’s. Two return train fares from King’s Cross to Doncaster were booked for a combined price of £82. The matter of sourcing a venue, however, proved somewhat trickier, at least at first. The Polish Club on Summer Lane were left a message that went unanswered. The Trades Club on Racecommon Road – the site of my mother and father’s wedding reception more than 45 years ago – weren’t able to give me an answer as to their availability until the weekend.

Even a phone call to the town’s best and most-central music venue, the Old Number 7 on Market Hill, did not begin with much promise. The woman on the other end of the trumpet wasn’t familiar with the name I was now touting around town. But she took the details anyway and said she would present them to the bar’s owner. This she did, and rang back the next day. By this point her voice had quickened a beat, and was raised by a semitone or two; a glance at the browsing history of the office computer would almost certainly reveal that the name ‘Frank Turner’ had been typed into the archives of YouTube.

We had a deal, and a gig. Frank now had nowhere to run, and no place to hide. Just as well, then, that he was in the market for neither.

‘It’s going to be quite the evening,’ he wrote in a reply to an email the number of which I was attempting, and failing, to keep to a minimum. He invited the young and emerging singer-songwriter Joe McCorriston to open the show – potentially a chalice brimming with poison: any Lancastrian travelling east across the Pennines soon finds himself deep behind Enemy Lines – and suggested that the Morecambe based 20 year old ‘trail’ the booking on his own Twitter feed in order to send the first of numerous smoke signals into the air.

At my end of the operation, I rang The Barnsley Chronicle – one of the country’s best weekly regional newspapers, and still the beating heart of the town it represents – and spoke to a reporter whose instincts for a story were either not sharp in the first place or else had been dulled by too many slow-news weeks. My opening gambit was, I thought, pretty strong: ‘Man who performed at Olympic Opening Ceremony and who has headlined and filled London’s Wembley Arena is coming to Barnsley to play in a pub for free.’ But apparently I was wrong about this. Two calls and one unanswered email amounted to a story that seemed no more important than an article about a dead donkey. (It was only when the details were spotted on the server by Ashley Ball, one of the paper’s younger reporters, that ‘The Chron’ decided to dedicate more space in a feature that will be published this Friday.)

Frank Turner himself, however, played a tactical blinder, a seduction that were it physical would make Warren Beatty look like Sid the Sexist. First he tweeted to his 135,000 followers that with nothing on his diary for the week, he might pay a visit to South Yorkshire. Then he ‘followed’ Old Number 7’s own Twitter feed. He posted train timetables to Barnsley, from both Sheffield to the south and Leeds to the north, the two cities in whose shadows the town will forever lie.

By half past ten on the morning of the show, the phone at the venue had been ringing as if it were the only pizza delivery service in a city that had yesterday legalised pot. Eight hours later, the only standing room to be had is on the pavement outside.

There is a larger point to be made here, this being that tours of Britain Ain’t What They Used To Be. In the 1960s bands such as The Who and The Animals would play towns such as Barnsley (in fact, the former acts excursion in support of 1969’s Tommy album featured an itinerary that included such ‘horse-on-holiday’ locations such as Wellington, Chippenham, Stockport and Morecambe). As late as the 1980s groups such as Rush, Metallica and even Bon Jovi were visiting Leicester, Bradford and Ipswich respectively. But as the 20th Century shuffled off into the past tense, the trend became that the ‘bigger’ a band the less comprehensive were its tours around our Sceptered Isle. Even major cities such as Newcastle, Liverpool, Leeds and Sheffield were left off the docket. As for places such as Sunderland, Southport and Chesterfield… well, the people there could go whistle the songs of the bands they now had to travel long distances to see.

But on the final Thursday of the summer, for one night only Barnsley does not the victim of such oversights. As Frank Turner arrives in this corner of God’s Own Country, the town is bathed in sunshine both literal and figurative.

Tonight concert in ‘Tarn carries no official cover charge. Instead, those lucky enough to gain entry to Old Number 7 are asked to make a discretionary donation to the Yorkshire Miners’ Welfare Trust Fund.

Despite it being now two decades on from the closure of the last of the county’s dozens of deep-cast pits – with Goldthorpe being the last of the Barnsley pitheads to fall – the ‘demise’ (the word is ‘destruction’, actually) of the mining industry remains a blight on my home town. It was an act of unilateral political vandalism so ruthless in its finality that even Norman Tebbit, the attack-dog of the Tory Right, was moved to say that he believed the manner with which an entire workforce was cannonballed onto the dole was “unduly harsh.”

This is just one of the reasons that while in the spring of 2014 UKIP were given democratic-license to run riot in nearby Rotherham, to this day the Conservatives are electoral poison around these parts, and will forever remain so.

Should anyone require evidence that this smouldering grievance can still be ignited by the merest touch of flint on wick, it can be found at the moment when Frank Turner announces the name of tonight’s charity. Hearing the words ‘Yorkshire’ and ‘Miners’ paired together again, 300 people, almost all of whom were years away from being born when The Strike began 30 years ago this past summer, begin chanting, with genuine force, “If the miners are united, they will never be defeated.”

Suddenly the sound is no longer that of a concert. It is the clamour of the picket-line.

By the end of the night buckets positioned beside doormen who were once themselves miners are stuffed with £5 and £10 notes. The bar staff at Old Number 7 will count the donations and announce a tally that stands north of eleven hundred pounds. Forty one of these pounds were donated by the headline act, who quietly threw the price of his train fare into the bucket.

As a London-bound East Coast Main Line service rolls out of Grantham station and gathers speed through the fields of Lincolnshire, Frank Turner sits on a table-seat next to a guitar case that has seen more luggage carousels than Alan Whicker. Last night’s gathering at Old Number 7 was his 1605th performance as a solo artist, and despite a steady stream of critical opprobrium from members of the Fifth Estate irritated that his success exists and has blossomed without either their permission or endorsement, Turner’s forward momentum seems as forcefully propulsive as that of the train inside which he is presently seated.

That the songwriter’s fortunes have changed is obvious, but the manner in which they have done so is at least partly obscure. He recalls that “for the first few years of my solo career I would get emails from people saying ‘Thanks for being the authentic voice of the working class’".

The fact that Frank Turner had made no such claim was quickly obliterated when it was ‘revealed’ that he had been educated at Eton. What was rarely mentioned – and now seems entirely disregarded – is that he attended the country’s most prestigious seat of secondary learning on a scholarship, an honourary stipend that singled him out as being the public school equivalent of the state-school kid who eats free school meals and wears second-hand Primark trainers .

Even today there are those who know that Turner received “the best education in the world” for nix and who believe this matter to be a smokescreen. The case for the prosecution points to a family history that features Captains of Industry and public school educations. But while it is true that Frank Turner’s father was also an Old Etonian, what is largely unknown is that the son’s relationship with this father does not glide down a smooth road and has incurred (and might still exist in) states of outright estrangement. As even the highest orders of the Aristocracy have learned, in modern Britain hard currency will always trump gilded lineage. I have been to Frank Turner’s mother’s home in Winchester. It is a nice but thoroughly ordinary house. I have also been to the flat in Islington on which he pays a mortgage and which he shares with a lodger, the residence to which his post has been delivered for the past two years. It is pleasing on the eye in terms of decoration, but it doesn’t have a garden. It is no nicer, and not much bigger, than my own flat two miles down the road in Camden Town. And no one ever got rich being a music journalist.

As for the matter of Frank Turner’s school days, that an institution as class-based as Eton should have within it its walls its own microcosmic and usually ruthless class-system – one described magnificently in Just Boris, Sonia Purcell’s biography of the Mayor of London – should be obvious even to those who have had no formal education, private or otherwise. Those who think that Frank Turner’s thoughts on this subject should be accompanied by the sound from a violin that would look tiny in the hands of musicians from Lilliput and Blefuscu are missing the point. There is a prejudicial element at work here (and in more than one sense of term, at that) and to deny this is plain intellectual fraud.

“The frustrating moment was when a lot of the people turned on me, as it were, when the facts about my education were disclosed,” he says. “They got angry with me because they built an image of me in their head of what they wanted me to be. And I turned out not to be that. And this is the most depressing thing, because it’s really the definition of prejudice. Rather than adjusting their opinions to fit the facts, instead they get angry at the facts.”

Actually, this isn’t the most depressing aspect of the story, at least not from an external point of view. More disheartening still is that so many people have eyes only for the story rather than ears for the songs. It isn’t that they’ve forgotten to trust the art rather than the artist, but that it has been forgotten that the artist produced any kind of art in the first place. And so as Frank Turner points to the moon, a band of idiots stare at his finger.

Except, that is, for the continued and growing audience the devotion and affection of which is as striking as it is unfathomable to Turner’s many detractors. In a small bar in Barnsley this truth is distilled down to an intense potency. It is the sight and sound of three hundred people who know full well that they represent one of the most derided towns in the country – if not the most derided – and who are utterly proud of this fact, standing in union with the a musician who finds himself the object of more inverse-snobbery than any other performer in contemporary Britain.

As the daughters and sons of Yorkshire chant their county’s name between numbers, and raise the memory of a workforce that was robbed of everything except its dignity, they stand enthralled as Frank Turner sings songs of an Albion that exists in the eye of his mind.

This is the best of our National Character. It is a classless society we all should applaud.