Where fans in the ‘60s may have read a handful of features on the Rolling Stones and felt like they knew Mick Jagger, the narrative was always controlled to a degree — at least until things got big enough to blow up in the tabloids, and a different frame was applied to the story. Today’s mass media and social media, meanwhile, are a ceaseless barrage of information – an attempt to configure a person by millions and millions of theoretically unfiltered pieces. We know where Taylor Swift goes on holiday, how Disclosure feel about British politics, what Moby ate for breakfast (it certainly ain’t got four legs or eyes I tells ya). But all that information only leads to performative selves and messages filtered through layer upon layer of abstraction, true of each and every one of us as well as much as those who come under the tag of celebrity: building an us-like character with each and every Tweet, Facebook update, Instagram post, and Snap, one that we carry around with us and that both accentuates and comes into conflict with the true core we wish to express.

As three of the largest-drawing and most impressive performances at Helsinki’s Flow Festival, ANOHNI, Sia, and Anderson .Paak bear that out, expressing unique identities and messages through complex balances of opposing aspects. And, depending on perspective, they may be real, complicated, difficult people, or they may be perfecting a message delivery style just as performative as the swaggering rockstar caricature of decades past.

Every day, we run a fine line between knowing everybody down to their most intimate details and not ever knowing anybody at all. The idea that you can never truly know anyone is nothing new, going back centuries, but it seems to have taken on a new flavor in the internet age. The idea that we can read others far better than anyone can read our selves, the illusion of asymmetric insight as it’s come to be known, is especially interesting when people put out so many pages of material to be read. This dichotomy has always been a particularly interesting when it relates to art, and specifically music; singers are so often immediately thought of as delivering something straight from the core, the “I” assumed to be autobiographical. There’s an emotional resonance to music that feels preternatural, instinctual. Yet even with the purest music there will be some level of smoke and mirrors, some element of enhanced performance of the (or a) self.

At Flow, the duality of the raw and the artifice couldn’t have been more apparent, often split down lines of age and experience. ANOHNI delivers songs with an evocative poetry, both in her lyrics and voice. On Hopelessness, they increasingly and explicitly reference the hardest of realities, from the specific terrors of climate change to the tragedy of childhood in a war-torn country. And yet, on stage, ANOHNI’s performance comes in negating specificity. Her face remains covered in a fencing mask-like veil, expressions relegated to arms writhing and hands clawing at the air. A wave of surrogates passed across the giant screens, women mouthing along to vocal lines and eventually crying, makeup and tears streaming down faces.

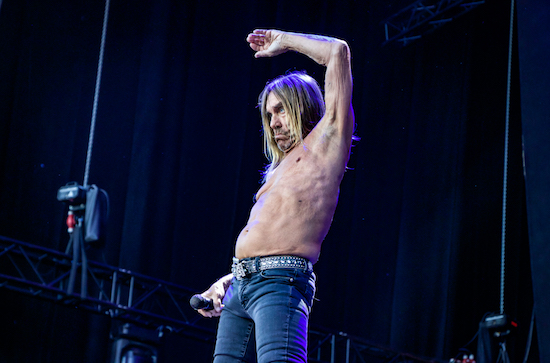

Older performers, meanwhile, seemed to be approaching this dichotomy of self and performance in perhaps less complex though not entirely different ways. The ever-irascible Morrissey would never cover his emotions, dressed like a car salesman, singing and sneering his real feelings even when people can’t handle it (I could). Though he continues to have a massive following, for some his raw, opinionated persona just isn’t acceptable, so unlike the mediated style of the digitally split and digestible aspect of today’s age. Iggy Pop’s performance is so real that he wants everyone to feel his reality — literally, spitting at the crowd and (as always) revelling in his own skin with his shirt off, rolling sweat across anyone he comes near.

But, as anyone who has seen Iggy (or James Newell Osterberg, Jr., if you prefer) offstage can attest, there are obviously levels of the self that he projects onstage. He’s not a perpetually cranked maniac, reserving this version of self for the stage to better convey his ‘Lust for Life’. Moz … well, maybe he’s this contentious no matter where he goes, but he pounds his chest and projects to the back of the audience with the best of them. He knows he’s on stage and delivers. They also both have pretty static setlists, and as anyone who has seen an artist like this twice in the same tour can suggest, some moments that feel emotionally raw are actually repeated close to verbatim. There is performance there, not just a recitation of deep feelings – perhaps a form of self-preservation from controlling the emotions rather than weighted down by them.

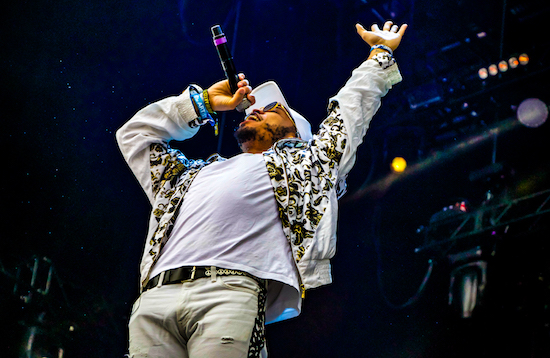

In some ways, Anderson .Paak hearkens back to this style of performative self. “I wanna say some shit,” .Paak begins at a key moment in his set, though interrupted by his guitarist noodling a bit. “I need to say something that’s on my mind and I don’t understand why the fuck you need to play,” he barks, a moment of apparent frustration at a perceived blocking of his need to speak his true mind. Yet, this too can all be written of as stage banter: performative expression choreographed into their set. .Paak’s a good actor and sells it (much as he does on the sublime ‘Come Down’), a little bit of old-school showmanship. But simultaneously, he’s using that as a frame for some seriously personal rap and R&B songs. His tunes detail toxic relationships (‘Put Me Thru’), hard times when he was stuck sleeping on the floor with his newborn (‘The Season/Carry On’), and the possibility to overcome all that in the moment (‘Am I Wrong’). He shatters his history, present, and future across his songs, and then uses a performed narrative to piece them together again.

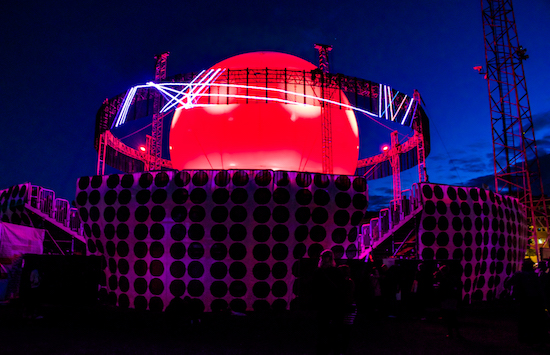

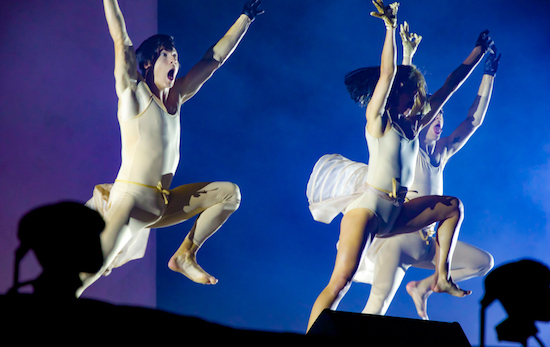

Working in the pop genre, the way that Sia guards her self increases in its audacity much the way her music does. This conflict of self and performance is not exclusive to high artists like ANOHNI: the giant hair covering her face and celebrity avatars are perhaps the most obvious version of this, but Sia’s conflicted expression extends far deeper, relating more closely to the expression each of us undertakes than ten inches of fringe might necessarily allude to. Her most recent album is titled This Is Acting, a reference to the fact that she initially wrote the songs included therein for other artists, but it also comments on the genre as a whole. Pop runs on massive emotions beyond the pale of the everyday, performed in ways that most would never perform them in their daily live.

But pop has also always held an exaggerated mirror, allowing us to vicariously live the extremes that we feel but can’t express. While decades ago the genre was angled at sincerity, Sia is the prime representation of its postmodern turn: the self-aware pop in which its power can at once be undercut by a lack of sincerity and doubled by its reflection of a reality in which no single emotion can exist on its own. While her songs like ‘Diamonds’ and ‘Chandelier’ hit all the right pop notes musically, Sia expresses her true artistry in her performance. She would sing something that sounded beautiful while her dancer embodiment howls at the moon, like the teenager who puts on a massive smile for a selfie to be published to the world and then returns to a pained grimace.

Art goes through phases, influenced by the expression available to the world at any given time. As the number and types of ways that people can explain their identity to others grow exponentially, it seems only natural that the day’s performers would include a reaction to that in the way in which they artistically express themselves. Sia and ANOHNI cover their faces in different ways, but only as an outlet to take on a form of control and framing that they choose, much the way that Anderson .Paak and Morrissey chose the theatric narrative framing. Though their styles may seem a million miles apart, Flow Festival proved that they were merely two sides of the same coin. Constant information often seems like it’s degrading and devaluing true connection, and we seem like we’re valuing 140 characters over true communication. But we know our musicians today no better or worse than we did 30 years ago, just the way we do each other. We may never truly know anyone, we just know them differently.