I have not had as many religious experiences in church as someone who believes in God arguably deserves, but I did undergo one of my most intense musical experiences in one, and I cannot rule out that it may have been divinely inspired. Far from home one Sunday, coming from a C of E culture that emphasised decency while rendering existence itself rather dull, I found myself in a room heaving with strangers, moved to stand and sing along to songs I had never heard before, on the verge tears for nearly two hours. Perhaps my evangelical unconscious was looking for an excuse to be comforted by the holy spirit and soar, after years of successful repression. That would be would taking something away from Ethel Cain though, who tonight was literally charismatic, her show suggestive of that service (tellingly also the work of North Americans) in a manner that only occasions bound by a deep structural resemblance can share.

There are certain stars who excite religious devotion in audiences. This can be shorthand for obsessive fans expressing cult like fervour, their adoration shrill, often kitsch, and sometimes negotiable. A religious hold over an audience is a deeper thing altogether. I have encountered it only rarely at concerts, in spite of Zappa’s belief that “rock & roll is the only religion that delivers the goods”, and even then, there is a difference between fans who simply love the music and those whose cherished sense of themselves is completed by their idols.

Unfortunately for a piece that wishes to emphasise Cain’s uniqueness, watching Lana Del Rey at Wembley earlier this year is one recent example. It’s hard to finish an article on ‘the Preacher’s Daughter’ without encountering Del Ray, and I am afraid I am incapable of escaping the trap, and Cain herself cites Del Ray as a major influence. The latter is a less intense example of the tendency, the love her audience have for her is more embodied in the personal than spiritual, though no less absolutist than the gasps and sighs of Cain’s fans that fill the gaps between songs. Questions of authenticity are besides the point with Del Ray, who is a self-created authentic myth, whereas Cain has encouraged the notion in interviews that she represents a more “real” America, less Norman Rockwell flying first class on PanAm than a 7-Eleven Flannery O Connor staring from her mobile home at a tattered Stars and Stripes. Adding another path to the labyrinth, Cain was born Hayden Silas Anhedönia, using her chosen moniker as a self confessed masque, her albums Preacher’s Daughter and Willoughby Tucker, I’ll Always Love You fictional narratives that do not address an American adolescence that either Tiffany or Debbie Gibson would have recognised, placing them nearer the concerns of Nick Cave, particularly in the symbolic conflation of love with murder and cannibalism. The assumption that she must be in on an act too ought to follow from this transparent stagecraft, but that is not how things pan out in Hammersmith, where her portrayal is as strangely honest as watching someone perform themselves while pretending to play someone else, revealing truth as they pretend to lie.

In spite (or perhaps because) of appearing on an isle of southern gothic signifiers, surrounded by a bed of dry fog and bathed in a light show that puts me in mind of the 1985 ‘farewell’ concert by Sisters Of Mercy Wake, her band marooned Yellowjackets who have survived an unnatural disaster, and Ethel herself emerging from behind a broken cross/ telegraph pole that acts as the lectern from which the service is delivered, the show feels very rooted in the American here and now. The songs (which the audience give note perfect renditions of) owe as much to the heartland of John Cougar Mellencamp, and the raw Americana of Michelle Shocked, as they do the antics David Lynch and Julee Cruise, Night Of The Hunter and a thousand straight to video American Haunting flicks. Tracks like ‘Janie’ and ‘Tempest’ are contaminated lullabies in aspic, their prettiness possibly driving the fear that she was leaving something important out, hence the release of Perverts, Ethel’s drone album and act of self correction. Her experimental tendencies and pop heart flatten and cohere live, sometimes even in the same song. ‘Vacillator’ becomes Perverts which becomes ‘Housofpsychoticwomn’, both sides lauded in a culture where the accessible – Preacher’s Daughter was her first US top ten album – and the esoteric have always hidden in plain sight. Like Prince, who continuously toyed with gender roles, mining sex and religion for chart hits, Ethel is a close observer of the America that bequeathed her, and whose public are never so indiscriminating, cruel, and anodyne as Coldplay’s record breaking tour round its arenas, and Trump’s re-election, might lead us to fear.

Religious music, of a conventional sort, is the other pivotal self confessed influence on Cain – along with Florence Welch – though one her English fanbase are less likely to have less personal exposure to, the white American Christian musical tradition having less popular traction than Black gospel and soul. From the Shakers who thought of songs as divine gifts, and the roadside revival meetings, where spontaneous baptisms and exorcisms prefigured rock gigs at their most unpredictable, to the Baptist gospel that she as a Southern Baptist would have had most exposure to, God was never too big a subject for pop-hymns. He was always part of the classical pantheon after all, and the emphasis was always on his presence being there, especially when you think it isn’t. This occurs time and again in her work. The concert brings the dynamics of the revival tent to the Apollo, the security scrambling about offering water to swaying fans and the music stopping on three occasions, once in the middle of ‘Tempest’, a song of such sedate beauty, that it almost prohibits a physical response, to stretcher unconscious members of the audience who have fainted from the hall.

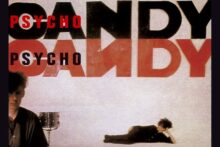

How crowds react to music, whether by pogoing or screaming until they soil themselves, is as liable to historicisation as any social more or medical diagnosis. One would not have to be present at Altamont to have attended hotter and more fiercely contested shows than this, and yet I do not think it is the heat alone that influences the crowd, rather a particular emotional response to the music that is allowed for and expected. The thrill of doing in front of others what you would not do alone, to experience the most intimate and extreme parts of ourselves in public, and the danger that it will all become literally too much, is the desired risk here, much as getting punched at a Jesus and Mary Chain gig or having beer poured over your head at a Beastie Boys show was for a less refined gig goer. The momentum is so intense that the interruptions make no difference to the atmosphere, the fact the show stops at all, levelling the metaphorical wall Roger Waters believed would always separate punters from their idols.

All artists have an understanding of their audience, even ones who affect not to, and the emotional pact her audience has with Ethel Cain constitutes a powerful energy in itself. Their wild responses to the minimal onstage banter so on cue as to nearly sound canned. The connection is not based on parasocial projection, so much as identifying with someone who instinctively knows what they are going through. Musically her lush ballads are pulled through the contemporary ringer by the faltering silence followed by the hell-unleashed dynamic of melancholy metal, and a liberal use of drone, which makes her too bass heavy to be confused for the low-end free zones of twee indie or sonically insubstantial emo. But it is in her extreme slowness – the bruised languor of ‘Waco, Texas’ is akin to starting a long book when you ought to be changing trains – that her passive resistance is apparent. A Gen-Z ‘go slow’ that pushes back against the speed of the gig and attention economy her core demographic encounter daily, turning her inwardness inside out into a radical outwardness.

This unhurried defiance is the antidote to hyper-accelerated digital stimulation and hyper-precarious labour, the blizzard of choices that are supposed to be meaningful and never are, her fans yearn after, the sacramental slowness of the music itself a devotional alternative to the haste and waste of the outside world. As with most of us, there is also an uncommonly normal side to Ethel, as evinced in the encore of ‘American Teenager’ where the lights go up, she dons a baseball cap and dances, wrapping a keffiyeh thrown by someone in the crowd round her neck, her political gestures as unremarkable to her base as they are shocking to the Fox Newscasters who call for her to be boycotted. The crowd love it and are overfull, I sense, of the feeling I look for in church, their impossible expectations and mine sated tonight with hints of the divine.

With thanks to Adam Jones for the after-show discussion.