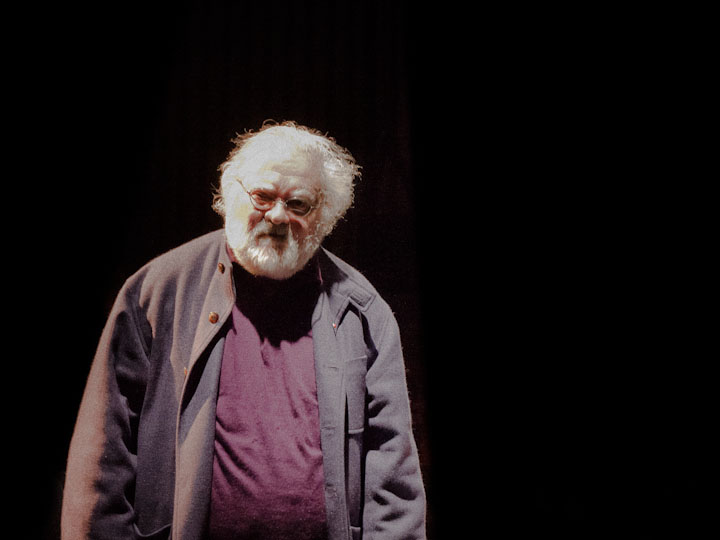

Pierre Henry, draped in an oversized coat jacket and sporting a purple sweater that’s losing its shape, slowly eases himself out of his chair and turns to face the audience sat around him. Photographers, banned from taking pictures during his performance, leap to their feet to try to get a shot. I’m amongst them: I crouch down at the end of the little corridor that runs between aisles of seats from his mixing desk towards the exit, and point my camera in his direction. The lights in the room are still dimmed, so I adjust my settings as he turns to make his way out and then faces me dead on. For a moment, as I take what will be my only picture, he fixes me with a formidable stare. It’s an intimidating look, part puzzlement, part infuriation, but it also seems to be asking me a question.

"You?", it says. "What are you doing here? Are you even a fan of Electronic Music? Do you even care about Art?"

It’s a good question, and one that I’ve come to Bergen, Norway to find an answer to. The 84-year old pioneer of musique concrète – sound collages that source from unlimited material – is one of the most prestigious names booked to play the city’s EKKO Festival of Electronic Music and Art, a concept as intriguing as it is vague. I’m not entirely sure what constitutes ‘Electronic Music and Art’: are these two separate concepts, or does the festival celebrate the point at which the two meet? If it’s the former, then there’s a good chance I’ll find something here to enjoy. But if it’s the latter: Bergen, we may have a problem.

I carry a suitcase of prejudices gathered in the mid-1990s while working as a junior publicist for a series of avant-garde evenings organised by the legendary Blast First label under the name Disobey Club. There, I’d done my best to embrace the rejection of traditional musical values while watching Philip Jeck manipulating turntables or Aphex Twin DJ with sandpaper and a food mixer – great for anecdotes, less good for the ears. There’s a splendid moment in the first season of I’m Alan Partridge when the bewildered DJ talks to Michael, one of the staff at the Travel Tavern in which he lives, and is nonplussed by the man’s Geordie accent. "That was just noise," he replies. This, I’m ashamed to say, is how I often felt when confronted by some of the artists that appeared at Disobey. I knew others could decipher what was being communicated, but I’d emerge from the club baffled and, ultimately, alienated. I worry that EKKO may leave me similarly estranged.

EKKO isn’t one of those festivals that find people in fields or shuttling between stages in a building, nor is it one where they congregate in tribes. It’s instead held in four separate venues in this small city, and would be best described as a curated series of unhurried concerts, of which, fortunately, my first comes in the form of Robert Henke and Christopher Bauder’s performance piece, ‘Atom’. It’s not actually the festival’s first event. Although most shows are concentrated over this final weekend of September, there was a party at the start of the month. Last weekend Planningtorock, Ungdomskulen and Brandt Brauer Frick were amongst the acts lined up for two nights of almost as much activity as the three days to which I have been invited. There will also be another party later in October to bring things to a close, and associated exhibitions run from March to November. But ‘Atom’ gives me my first taste of EKKO’s agenda.

Henke is best known as one half of Monolake, the minimalist, dub-influenced techno producers who were key to the success of Basic Channel’s Chain Reaction label, and also as the co-inventor – with Bernd Roggendorf and Monolake partner, Gerhard Behles – of Ableton, the software company favoured by huge numbers of electronic musicians. Bauder, meanwhile, is an award-winning artist specialising in interactive installations. The prospect is appealing, partially due to my deep love for a beautiful piece of twenty year old ambient, Berlin-inspired electronica that Henke gives away for free on Monolake’s website, and also the illustration used by the festival programme, which simply shows white balloons suspended in the dark.

It’s this, presumably, that is responsible for the sight of large numbers of kids seated on cushions around the carefully arranged 64 balloons anchored by electric cables to the ground of Studio Bergen, normally a contemporary dance space. It can’t be that Bergen’s parents consider it healthy for their children to spend the best part of an hour having their ears pummelled by a combination of sounds that range from malfunctioning clocks and twitching percussion to extreme bass and abrasive techno, often within moments. The kids block their ears, but they, like everyone, are transfixed by the sight of the massed balloons rising and falling in changing formations, white lights installed inside flickering on and off, all triggered by the music. The sounds and sights are like a migraine, disorientating and intense, and yet it’s a fabulous experience. There’s a condition called synaesthesia, where the stimulation of one sense provokes a corresponding response in a different sense, and this is about as close as I’ve seen anyone come to replicating that with such stark simplicity. The fact that the music, for all its perfect sound and intensity, almost certainly won’t stand up without such visual accompaniment does nothing to reduce the impact of the performance. The two are meant to interact. Electronic Music and Art: 1. Indie Wyndy’s Cynicism: 0.

Crowds gather the following evening in USF Verftet, once the country’s largest sardine cannery. Here, Electronic Music and Art collide in a rather different fashion, with sound installations exhibited in the foyer. A wall filled with tiny speakers that emit a hissing static from a distance offer individual tones if one moves closer, ears deciphering notes depending upon where one stands. Small sculptures built out of circuitry respond to light and shadow with – inevitably – more electronic sounds, and people gather to wave their hands nearby, as though playing a Theremin of restricted abilities. Nearby, sheets of paper with graphite illustrations respond similarly to touch. Each piece is briefly fascinating, but I can’t help wondering whether I’d be equally riveted if I were to dismantle a beloved <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simon_(game)" target-"out">old Simon toy from the 1980s.

In the main hall, renowned guitar improviser Stian Westerhus and Jaga Jazzist keyboard player Øystein Moen have teamed up with Susanne Sundfør, a Norwegian singer songwriter of considerable reputation. Performing under the name White, they set up on a stage temporarily erected in the middle of the room beneath a white drape that hangs so low that it grazes Sundfør’s hair when she stands erect. Amidst a blinding fury of predictably white lights, they churn out a doom-laden clamour of analogue keyboard throbs and Sonic Youth guitars, though, in this light, with the collars of his black shirt turned up, Westerhus looks more like Blixa Bargeld. Sundfør meanwhile taps her feet awkwardly during the most aimless moments, or crouches down during extended instrumental sections as though she’s readying herself for a 100 metre sprint.

It’s hard to know why, but Sundfør and I have never got on musically: I’ve always found her po-faced, despite the protestations of many people around me, and tonight’s no different, though for some strange reason I always feel guilty about this response. But paper on her music stand condemns her with lines like, "All praise the crystal ball, all hail / Come now everyone, praise the crystal ball", and this portentous but ultimately empty language is reflected in most of the music that accompanies her. Towards the end, they stumble into a genuinely impressive jam where Sundfør’s vocals seem double tracked, and a pulsing rumble is transformed into what could be an exceptionally depressed Massive Attack during their Liz Fraser period, but then Sundfør reaches up with a Stanley knife to slice open the tarpaulin overhead, and the whole affair takes on the appearance of an over-sincere student drama experiment. The only sensation I’m experiencing as things grind to an end is that my legs are getting rather tired.

The claustrophobic sheet now gone, the stage is cleared away, and Put Your Hands Up For Neo-Tokyo appear in the more conventional setting at the end of the room. It’s a suitable place for their surprisingly unadventurous pop: despite banks of keyboards and a Korg keytar around the singer’s neck – though this also risks provoking another prejudice based on memories of Bros – it’s hard to grasp why they’re at this festival. Recorded material like ‘The Blood Of Brethren’ suggests a playful employment of electronic sounds in their work, I admit, but live they’re a disappointingly uncharismatic indie pop band with a penchant for mildly complicated arrangements and perplexing rhythms that together sound a little like Supertramp’s 1985 album, Brother Where You Bound. In itself that’s not a bad result, but it’s unlikely to have been their intention, and here the band stick out like nipples in winter.

If you’re going to make electronic pop, far better to be Casiokids, whose boundless enthusiasm and guests dressed as bananas whip a packed hometown crowd to a creamy peak. Their main singer, Ketil Kinden Endresen, perhaps still smarting from my recent review of their performance at Trondheim’s Pstereo Festival – in which I suggested he looked like he was "conducting a geography lesson" – now prances across the stage with far more energetic conviction. (Yeah, of course he reads The Quietus, and that’s the power we wield, man.) Around him, band members swap instruments and grin uncontrollably against a backdrop of cartoon clips and Eastern Bloc TV presenters. It’s Electronic Music, for sure, but – despite balloons thrown to the audience as big as Henke and Bauder’s – with squelching tunes like ‘Fot I Hose’, the only ‘art’ here is in ‘party’. This, I should add, is not a criticism.

120 Days round things off with a dramatic performance notable for another lavish lightshow. Their manager has tracked down The Knife’s star stage effect, and they perform amidst almost ceaseless strobes that fill the club with a near-death brilliance punctured by sci-fi laser beams. The Norwegian act, whose second album is finally readied for release, fling themselves around behind towers of technology like MC5, pumping out a savage stream-of-consciousness music: Primal Scream during their XTRMNTR period, or, more poetically, Underworld losing their shit. First album favourites like ‘I’ve Lost My Vision’ are given alloyed chrome on their motorik wheels, while the three part trilogy, ‘Lucid Dreams’, straps on Terminator armour. This is electronic music as rock ‘n’ roll, and yet there’s plenty of art to what they do.

We’re back to Studio Bergen on our final night, this time for Pierre Henry, where we find a collection of around fifty speaker cabinets arranged in front of us, lined up on plinths of various heights or hanging from the ceiling. We crane our necks, mystified, towards the crumpled figure with the aging poet’s hair sat behind a mixing desk buried within the crowd. He’d cracked his knuckles like a conductor when he sat down, waiting for a minute in silence before he started sliding faders slowly up and down, ostentatiously lifting a liver spotted hand each time one reached its goal as though he’d just majestically struck a piano key. But any relationship between his actions and what we are hearing is proving hard to fathom, even more so when it starts to seem that the experimental sound collage is actually coming from a CD player.

My own response is initially sceptical: I may have a beard, but it doesn’t mean I have to stroke it. I’ve been informed that Henry is phasing the sounds we’re hearing – birdsong, Hare Krishna chants, church organ toccatas, pan pipes, gunshots, brass and drums, bells, and much, much more – so that every individual in the audience is hearing a different performance, depending upon their proximity to each speaker. But I wonder whether his presence is entirely necessary because, try as I might, the only effect I’m noticing is the occasional, mild panning of sound between speakers. There’s also no apparent sense to his material – these cut and paste sound collages seem entirely random. But with mobile phones switched off, photography barred and no performance to watch of any sort, I’m forced to focus entirely upon what I’m hearing, and slowly, strangely, I find myself increasingly caught up in the aesthetic.

It’s an enormous surprise to realise that I’m starting to acknowledge a craft in his work, whether or not he’s participating in it tonight. For the most part, although I’m not recognising in these lengthy pieces any conventional form or melody, I’m creating some kind of narrative framework in my mind, and the extraordinary variety of source material is also conjuring up mental images. There are no balloons here to do the work for me, and yet I’m experiencing some kind of synaesthetic response. Normally, when faced with this kind of tunelessness, I would simply switch off the CD, as I did when I listened to Variations pour une porte et un soupir in preparation for the show: it’s essentially the sound of two balloons – yes, more balloons – being rubbed together. But tonight something very odd happens when he finally ‘performs’ his encore, ‘Psyché Rock’, known best in its Fatboy Slim-remixed form or as the theme tune to Futurama: I find its ‘Get Off My Cloud’ chord structure rather dull in comparison to what’s preceded it.

Clearly I’m not the only person in the room who clings to melody and rhythm as the basis of their musical tastes – my chair starts to vibrate as the beat kicks in with feet tapping the wooden floors around me, and heads start to nod eagerly in recognition of something at last approaching a real tune. This, however, makes me think of artists like DJ Shadow, which in turn reminds me just how many people have built musical careers around the aesthetics that Henry is employing, and I wake up at last to the extraordinary debt we owe him. Even though Henry’s ideas seem, by today’s standards, a little tired, the leap of imagination that he and his contemporaries took at the end of the 1940s opened new avenues in a fashion that must have been a shocking as the first sight of Elvis Presley’s hips a little less than a decade later. As with Henke and Bauder, it’s perhaps been more about the experience than the music itself, but the memory of both their shows lingers with me long after I’ve returned home. I’ve come face to face with one of the earliest, purest forms of Electronic Music and Art, entirely focused on breaking (formerly) established rules yet still disciplined and intelligent, and, against the odds, I’ve been won over.

After this, it’s something of an anticlimax to wind up the weekend in Landmark, a café-cum-gallery by day, quasi-club by night. There’s a DJ playing as I arrive, but he’s not what one might call a craftsman, and he’s followed by Swedish blisspop act Sail A Whale, presumably named after a misheard Enya tune. They perform silhouetted behind a white sheet on a ledge above the entrance, and the initial confusion this causes is furthered by the news – spelt out in letters projected onto the sheet – that the first tune we are hearing is not actually Sail A Whale at all. Ah, those pranksters. When they actually begin their performance it offers a brief sense of pleasant nostalgia, but it doesn’t take long to realise that this has more to do with their sun-bleached footage of 1970s Eastern European street riots than the emaciated manner their music comes across as they perform, which sounds like M83 after a couple of melatonin and a mug of creamy hot chocolate.

No one minds much. It’s Saturday night, after all, and Optimo are now on the decks. Sadly, while it’s not going to be hard to persuade me EKKO’s been worth the journey, you’re not going to persuade me to join you on the floor. This hasn’t been a 24 hour party under the midnight sun. There’s little danger of me accidentally going home with a fat, drunk, racist prostitute, as happened just the other day. This has instead been a weekend of contemplation about simple things I’ve taken for granted: the manner in which electronic music has become commonplace, and the seemingly infinite possibilities it still offers. I’m grateful for the reminder. I shouldn’t have needed it, but I did.

"Do you like Electronic Music and Art?"

"Oui, Monsieur Henry. Rather more than I realised. Fuck it, do you want to dance? There’s a blender behind the bar, and perhaps a scourer we can use for sandpaper…"