The bartender at my local is covered with tattoos, and when he tells friends good-bye, he says, “See ya later, motherfucker.” Randy is also an abstract painter, though he admits he hasn’t figured it out yet. He insists that his pictures aren’t finished until whoever is buying the painting has drawn some lines on the canvas themselves.

Meanwhile, I’ve seen two unrelated punk bands recently—one Viennese and one American—who routinely send their singers out into the audience to confront, flirt with or provoke the onlookers. This isn’t anything new: renegotiating the line between artists and their audience has just become established as part of the job description for many underground creative types.

The youth might call this interactivity, but the idea has bookended my creative life. As a teenage punk in Austin, Texas, I loved a local band called the Big Boys, who invited the audience to join them onstage at every show. Now, nearly forty years later, I am editing a book of my photographs of that Texas punk scene. For me, the most successful pictures are the ones which capture an interaction between audience and performer.

So my ears pricked up when I began to see posters around Vienna which featured photos of what looked like DIY punk bands and the words New Society. The organisers of this year’s Donau Festival in Krems have built a program around the theme of cultural cohesion; festival director Thomas Edlinger has wondered out loud and in print about the distinction between society and community. Is this a zeitgeist thing? Is there a change in the wind? Or is this just hot air? I decided to go to Krems for an answer. I discovered a lot of different definitions of “community,” and more than a few ways to break through the fourth wall.

Only a handful of the performers at Donau played with the audience in a physical way, although several of them have tried that before and discarded the method. The American provocateur Eartheater, a.k.a. Alexandra Drewchin, admits that when she has stalked into her audience, she has sometimes gotten into “hairy” situations.

On the other hand, the Alien Parade used one of the most ancient, and possibly silliest, forms of audience participation to turn the festival’s opening night into a street party. The Parade is the brainchild of Markus and Micha Acher, who also lead the Notwist, and in Krems, this bohemian march of horn players and audience members toodled across town, stopping traffic and waking the neighbours. One of their numbers sounded like the theme from the blaxsploitation classic Shaft, but the Aliens were singing,”Wir bauen eine neue Stadt!” As we passed under the Linden trees of the town park, people began using the trash cans as hi-hats.

A bit later, I pulled up next to Markus Acher to say it felt like a demo.

“We started doing these parades in Munich, in a part of town that’s quite rich,” he explained. “It was a way to take back that space. Munich is becoming very clean. A parade is a very old thing, but it’s new… new to us.”

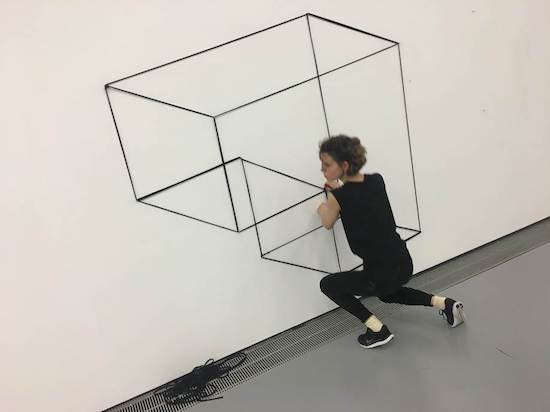

The next night, the transgender electronic performer N-Prolenta did indeed hop off the stage in the Minoritenkirche and plunge into the audience. But the most provocative audience intervention of the festival happened across the hall, during a performance by Karin Pauer and Aldo Giannotti. In this is where we draw the line, Pauer and partner Arttu Palmio use stuttering dances and what look like long black shoelaces to work the audience like a sculptor works clay. At what Giannotti calls the “soft spot” of the performance, Pauer and Palmio transform the audience into a swaying, bobbing disco crowd. What had previously felt like an episode of Black Mirror now felt like Studio 54.

When we spoke afterwards, Pauer offered a graceful distinction between community and society. She said, “Community is something you choose.”

Nevertheless, choice itself may be overrated at a festival such as this. At one point, I bumped into Thomas Edlinger in a hallway, and we chatted for a moment about the danger of giving people too many performances to choose from—no matter what, you may feel like you missed something. In How Music Works, David Byrne writes about the way musical scenes or communities develop through chance encounters and the intermingling between musicians and fans. In this regard, the Donau is very successful. In the past and again this year, performers get offstage, then go see other bands. It’s easy to walk right up to a choreographer, filmmaker or drummer and tell them, ‘I loved your show.’

Over the second weekend of the festival, the British experimental rock duo Guttersnipe became ubiquitous in these spaces: they saw everything they could, from Columbian experimental songwriter Lucrecia Dalt to the gender-role horrorshow that is choreographer Ligia Lewis’ eerie Water Will (In Melody). Perhaps they were taking notes. I also saw a charismatic dancer in Lewis’ show, Titilayo Adebayo, shaking her groove thing to at least three very different bands.

Unfortunately, while all of this was happening, I really did miss something important. My favorite punk band in Vienna, anarcho-primitivists Lime Crush, played a surprise show in the cantina of the football stadium next door. I missed it because I was eating french fries with Guttersnipe.

“Oh, we just did what we always do,” said singer Veronika Eberhart when I met the band later. Which means that Eberhart marched through the crowd, cheering them on, whooping and sweetly singing about squatters, police violence and pizza.

Eberhart is also a visual artist, and is presently writing a book essay about the stage. That makes sense, because as a performer, she tries to get away from the stage as much as possible. After speaking with her at Donaufestival, I realised I had missed another thing: some performers here and elsewhere in 2019 aren’t merely trying to forge more intimate connections with their audience. They’re also trying to sever their connection to the performance space. Or at least re-invent it.

During their performance, Planningtorock sang from a riser—in other words, a stage on a stage—danced along with a video of themselves, showed a home movie, and told the audience, “I could never have come out as a queer, non-binary person without music. I love music and I know you love music.”

Some might say this was Too Much Information, but for me, it was a sweet, smart way of erasing a barrier.

Two electronic performers attacked the same problem with opposing methods. The Turkish-German artist Hüma Utku redefined DJ performance: as she unleashed a wall of dread and monster basstones, she threw her head back, flipped her shawl out like a cloak, and fluttered her hands in front of her, as if she were making an invocation to forgotten gods.

Giant Swan, an English duo, made a sound that was nearly as bottom-heavy and funky as Utku’s, but instead of dramatising themselves, they tried to disappear from the stage by becoming their own audience. They flailed around like the dancers in the front row. For a moment at least, it looked like the crowd had colonised the stage, and even the limbs and stomping feet of the people making the music.

A week later, the audience fell deliriously back down where it belonged. During Yves Tumor’s performance, everyone knew who was the Star. In a marvelous inversion of expectations, Tumor worked the stage like the first real 21st century rock star, but the lighting barely illuminated his face. The music sounded to me like an insane fusion of Prince and My Bloody Valentine, but the classic shapes Tumor was throwing suggested that Mick Jagger and Tina Turner were together again in the same body at last.

The crowd was grinning brainlessly. At one point, the swooping, tweaked funk of Tumor’s samples ceased, and he crossed back to his machines. “How is it out there?” he asked as he twiddled. “Is it loud enough?”

“Louder!” screamed the people around me.

“Aaighht,” Tumor said from the side of his mouth. He returned to center stage, stared out at the sound man, and said, “This right here, these mains. Turn them up. Turn them all up.”

Is that any different from classic rock hijinks of days gone by, when someone like Bono would ask, “How you doing, Berlin?”

No and yes. Tumor was clearly playing with pop history, but this transmission of instructions from fans into performance and back to fans is operational in a way that Mick Jagger may have never been.

Back when Jagger mattered, bands played concerts and tours to promote their records. These days, musical groups tour to make money so that they can record themselves. Perhaps performing live has become a form of R & D: research and experience and dialogue with an audience, all of which will inform their next album or stage production. Artists travel to learn where they are going.

Two young Brazilian bands, Rakta and Deafkids, play, and both sounded like scientists when they talked about touring. Deafkids, who play punishing outer space punk, described their shows as attempts to manipulate the bodies in the audience. Rakta make dark, gothic electronica, but bassist Carla Boregas sometimes allows herself a nearly imperceptible smile. When I ask them what they learn when they tour, Boregas said, “We learn about people.”

Given all of this, maybe Donaufestival should be described as a workshop. This year’s star pupils were Guttersnipe. Before and after their Saturday night performance, the band paid attention to everything else, and barely spent a minute in their dressing room.

Their stage names are Uroceras Gigas and Tipula Confusa. Their show was a free-form freakout: Tipula rolling his eyes into the back of his head as he beat Godzilla sounds out of his drums, and Uroceras’ guitar like sheets of acid rain and Bugs Bunny cartoons. As these car crash heart attack sounds washed over them, the audience responded with interpretive dancing and goofy grins.

At the edge of the stage, Guttersnipe had set down one of their suitcases–perhaps they hadn’t had time to unpack. I asked them about it later, and Gretchen summed up the Guttersnipe theory of audience participation with the most punk rock thing I heard at Donau.

“I always thought it was funny when a sound crew set up the equipment, and then the band just appeared. When they finished, they just disappeared again. I like for the band to set up their own gear and then the audience sees it and thinks, ‘Oh, that’s how they do that. That’s how I could do that. I could do that.’“