"Why are you here?" asks the girl with piercing blue eyes, swaying slightly in the lights outside the lift that carries the audience five floors up to RAGU, a restaurant pressed into service as a nightclub for CTM Siberia. She presses us further, asking: "Is it exotic for you, to be here? I do not understand. This is a dark place."

Novosibirsk, founded at the point where the Trans Siberian railway crosses the Ob River, is hosting CTM’s first excursion outside of its Berlin base, where since 1999 it has provided a musical parallel to the annual transmediale arts festival. This two-leg event, the first half of which took place in the city of Krasnoyarsk, 800 kilometres to the west, was the brainchild of the Goethe-Institut, which since the early 1950s has sought to encourage cultural exchange between Germany and the rest of the world. Picking up on a local electronic music scene that seemed to be thriving without much infrastructure, the Goethe office in Novosibirsk worked with CTM to bring artists from Germany and elsewhere, such as Lorenzo Senni, Helena Hauff, Byetone and Rabih Beaini, to play alongside – and this is very much alongside – young Siberians. The majority of the festival production and booking has been done here, and there’s a relaxed feeling to it all, with a hope from the German side that people might see things are done and can be done. The locals (if ‘local’ is appropriate in such a vast country) hardly need much encouragement, with the likes of genial sound artist and composer Stanislav Sharifullin working themselves into the ground as they perform, organise, and lead us in a merry dance around the streets of Novosibirsk.

There is a huge weight of history between Germany and the empty spaces of Siberia. As one of the Germans here remarks, "There is a feeling in Germany that Siberia is a place where you go and never come back – most of our grandfathers were sent here as prisoners in the war." The vast expanse of Russia’s largest region could gobble people – or non-people – up with ease. As someone I speak to in Novosibirsk explains: "People were forced to walk hundreds of kilometres from their towns to the railway to take them to the Gulags. They were scattered like dust to the wind, and near the tracks in the forests you can find their bones, just under the leaves."

As I leave England, the argument about whether or not Jeremy Corbyn ought to sing the national anthem is still dominating the news. The ‘victories’ of three world wars, two very hot and one cold, has unfortunately given the British a myopic, nostalgic view of the 20th century, distilled now into jingoism, the horrors wiped away by a "Keep Calm & Carry On" tea towel. To us, Siberia is a place from spy novels, an abstract negative space of communism, a belief system ‘we’ defeated 25 years ago. In Novosibirsk however, the 20th century is ever present. Indeed, I think it could be argued that, along with the 1917 revolution, 1941 Nazi invasion and collapse of communism, Russia is experiencing a long 20th century, with former KGB man Vladimir Putin part of a continuum. It’s only a smug ignorance that leads us in the UK to believe that we are not a part of it.

One of the artistic projects I hear about in Novosibirsk is the idea of "talking about the weather": politics are not a safe subject for discussion, so coded descriptions about the human universal’s favourite subject for a quick chat are used instead. Discussing politics, or reading political meaning into the work of any of the artists playing, is therefore not only problematic – there are nuances to the way Russians approach political thought that are very difficult for a Western mind to latch onto – but also potentially dangerous.

In a forgotten corner of one of Novosibirsk’s parks stands a grey monument to the victims of Stalin’s purges. It was built during the 1990s after the fall of communism, but now looks neglected – some tiling on its four pillars is splitting, and there are a few tired flowers scattered about. People walk past without giving it a second glance. Just behind it, a huge new apartment block is rising on the site of the former NKVD prison, where unknown numbers of local people, including relatives of some I meet, were shot. In the early stages of construction, local journalists started demanding an excavation, but the police shut the site down and the flats went up on the bones of the dead. In Novosibirsk, 30 per cent of new apartments are unoccupied, bought as investment opportunities by Russians who made a fortune from oil and gas.

Memories – real, imagined and falsified – shape Novosibirsk. The giant opera house in the city centre was originally designed in the constructivist style during the late 1930s. Delayed by the Second World War, it ended up a hulking mass of neo-classical pomp, with gigantic wings extending the backstage into the streets either side to allow cavalry or armoured cars to pour across the back of the set in particularly dramatic scenes. Just behind the opera house is a park, quiet in the early evening and full of decaying children’s rides – water rafts, swing boats, a couple of trains, a shooting gallery. A maintenance yard built of shipping containers ("Property Of Tiphook Container Rental Bromley, Kent") sits in a corner, a radio blaring inside, and the only words I hear in English from it come from Tilda Swinton. This was once called Stalin’s Garden, and was built on the site of a former cemetery. Workmen arrived overnight to remove the memorials and the next morning members of the local Jewish community wept as their neighbours danced the foxtrot where the graves of their ancestors had been.

When I learn this, I feel uncomfortable about the the touristy photographs I’ve taken of the decaying rides, Soviet-era apartment blocks and iconography, feeling somehow complicit in shoring up these secrets and forgotten histories. A teacher I speak to tells me that none of his pupils have any idea about Stalin’s purges. Under the contemporary regime, which thrives on a potent mixture of nationalism, capitalism, cult of strength and the resurgent Orthodox church, some histories seem best forgotten.

Trying to review and make judgements on music feels difficult in that context. I am also wary that my political take on the place and situation could put Russian artists alongside views that they don’t subscribe to, which is partly why I’ve included my musical highlights of the Festival below.

In a talk on the festival’s opening night, Robert Henke remarked that "the beauty of globalisation is that our generation, and the ones to come, have access to the world of sound". This might read like a rather naive statement, yet after four bewildering, stimulating nights, it reflects the optimism of this strange festival in the back of beyond. This is why CTM Siberia is an inspiring and hopeful experience, where a new generation of Russian artists, internationally connected, are creating their own futures and narratives in a way that’s at once very familiar and unlike anything I’ve seen in the UK or wider ‘West’. Credit should be given to the Goethe-Institut for such a hands-off approach (one that contrasts with the aggressive commercialism of most European music ‘export’ bodies) that seems to have blown oxygen onto already glowing sparks of what might well become one of Europe’s most exciting electronic music scenes.

On the Sunday night, there’s a closing party in Novosibirsk’s first nightclub, a square box of a room plonked as if from above in the middle of a courtyard, surrounded by offices. Sharifullin organises a whip-round, with everyone asked to contribute 500 roubles towards a fund to purchase a synth for one of the Siberians, struggling to afford to buy the equipment he needs to move his music forward. Just before Helena Hauff plays, the venue empties and we all gather in the courtyard under the gathering dusk for a presentation, a speech, cheering that buoys everyone through until the very small hours of Monday morning. Yes, this might be a dark place with tensions and issues that are difficult for the Western European mind to unpick. But the spirit here is not exotic at all – it’s honest, very real. What’s more, everyone emerges steeped in a conscious internationalism that feels more and more needed in these strange times.

Selected Highlights Of CTM Siberia

Kathy Alberici & Federico Nitti

Drum Eyes member Kathy Alberici loops and manipulates violin to create an uncomfortable, mournful and sickenly woozy air in the foyer of the Novosibirsk State Philharmony. Federico Nitti’s visuals cleverly accentuate the disorientation, dissolving live footage of Alberici into grey pixellated blur that stretches my eyes, exhausted from an overnight flight. It sends me off into a bit of a daydream, and without noticing the set gracefully drifts from classical lament to cosmic sci-fi whirr and drone yet with its essential, elegiac core intact.

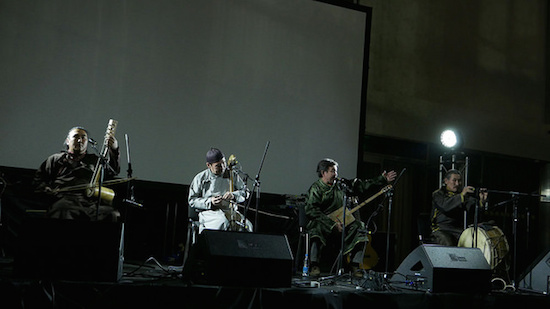

Huun-Huur-Tu

Such whirling magic sounds wonderful done via electronics of course, but to hear Tuvan throat singer do the same within one set of vocal chords is a rewiring of the auditory senses concept of what music can be. One of the four musicians, all dressed in robes of varying colours, picks out a line on one of their stringed instruments worthy of Michael Rother at his most hypnotic and then… It’s one of the most unusual vocal noises I’ve ever really heard, more liquid than anything else, flooding into and filling this room with ancient sound. It’s incredible to witness, one person’s voice generating a bass note drone and a higher tone like a Celtic whistle. When the full ensemble join in with bowed instruments, drums and other percussion, it’s all rather jolly. There are so many things in the globalised world that connect us across the continents, like those shipping containers in the nearby park, and some of Huun-Huur-Tu’s music reaches beyond the borders of the Republic Of Tuva to hint at sounds from further afield. I pick up on African desert blues, and even some of our own folk traditions – perhaps throat singers once wandered to ancient trackways of England.

Rabih Beaini & Daniele De Santis

The horror of the lone hippy drum player is a potent one. But Daniele De Santis shows how it can be done creatively, even if some of the more intense moments undoubtedly reveal a glimpse of his sex face. Hands dart and flutter and fingertips scratch over the skins, a rattling that becomes a rhythm you could imagine transposed from animal hide and recast in steel and concrete techno. As was the case with the Tuvans, it’s rather difficult to connect what’s being seen with the complexity of what the ears are hearing, especially when Rabih Beaini messes with the stabbing clarity of the rhythm by adding drones, Wurlitzer madness, squealing garrulous discord, high frequencies and some ethno forgery Clangers "whee woo".

KP Transmission

A rolling rumble, machinery heard underwater. Melodies submerged in a sump of thick engine oil. On the screen behind Karina Kazaryan, who hails from "the darkest suburbs of Siberia’s Omsk" footage from Dr Pavlov’s experiments are broadcast in gruesome detail, interstitials explaining why a dismembered frog is still twitching on its laboratory gibbet: "if the brain is destroyed then stimulus still provokes contraction". A track starts banging around like TG’s ‘Discipline’ as Pavlov’s dog is given an electric shock. It’s unnerving and rather excellent with it.

Foresteppe

Another local, resident of a small town just outside Novosibirsk, Egor Klochikhin explores traditional concepts of Russian historical identity. Playing in front of projections of illustrations from what must be a Russian folk tale – there’s a man in a bear costume and some sheep – he lulls the concrete of the Globus theatre with wonderfully executed folk and electronica. Yes, wait, come back! It is folktronica, but not crap! Klochikhin plays wistfully lilting music with acoustic guitar and, another track, looping bells, clicks, rattles and one of those toys that you invert to make it go "baaaa".

Dasha Rush

Dasha Rush starts off with Eno-esque ambience, (Music For Steppes, before a spoken word passage, scratching like quills over rough paper and glitchy electronic squits and pops. Then there’s aviation roar, bird song, vocals that have her sounding like a French Tricky. The everything and the kitchen sink chaos eventually subsides as a voice intones "No credit card no health insurance no passport no driving licence no credit card no visa no work permit just dust", which can’t help but have a powerful echo as Europe’s borders collapse in the face of the Middle Eastern refugee crisis.

Raving At RAGU

RAGU, a glass venue that bulges in the middle of its eight stories like a vertical slice of London’s Gherkin, is a curious place to host a nightclub. Usually it’s a dinner party place, and at one point I notice I’m dancing next to a stack of thick menus bearing the slogan "Racy & Glorious Union Since 2013". The windows looks down on the St Nicholas Chapel, which had a gold dome, and once conveniently marked the centre of the Russian Empire. Most of the crowd here are incredibly young. There’s a kid with a Confederate flag wrapped round his head and a flat cap on losing his shit. And to what? This is a night rather startling in its sonic diversity. Appleyard, from the remote village of Lesosibirsk, plays rattling misanthropy that when it gets going has people moving like Pavlov’s frazzled frogs. (It’s worth a trip to his Soundcloud to listen to both Appleyard compositions and a series of excellent remixes of many of the other artists playing CTM Siberia). It seems to be the politer, housey sounds of Mujuice that many of the crowd are here for, however, and the Moscow-based artists provokes frenzied and unhinged simultaneous pogoing and rather folkish in-time hand claps – except for one couple at the back having a school disco slow dance. Self-conscious Boiler Room shoulder shuffle this ain’t. Best of all, and a highlight of the Festival, are the duo of Love Cult, who seem to be at the hard of what’s going on in left-of-centre electronic music in Russia at the moment. Indeed, Appleyard has recorded an excellently brutal track called ‘Morphosauna – Love Cult Tribute’ that can be listened to here. Though they struggle with the sound (it is difficult to hear Anya’s vocals) the pair have a magnificent energy, blasting whip crack and rattling high treble out across the weird restaurant light fittings that look like onions. There’s a great kinship here with Berlin-based Oake in the initial, more abstract vocal parts that fit with Love Cult’s excellent self-description as "fuck ambient noise pop" before building through murky snare and hi-hat in tattoo above earthy drones. Everything is at odds with everything else, suddenly exploding into goth jungle over a noise that sounds like Satan’s hair drier, which is enough for me and ought to be for you too. Do check out their Bandcamp, though, as Love Cult’s recorded output is a lot more… sensuous than that live description suggests.

Mårble

Anton Glebov is at the heart of Novosibirsk’s nascent electronic music scene, running a cassette label and making music under a variety of names. In the second theatre at Globus One on the Saturday afternoon, he and a second musician make a watery, eddying set withwind chimes, synthesisers, recorder, Sigur Ros "ooooeeooo" vocals, psychedelic guitar, loops, sometimes at cross purposes in a blurry haze. It’s good to hear the sound of people finding their feet in front of you, pushing themselves while doing it, something that can be lacking in experimental music back home, where the "experiment" bit has already been done, leaving just the polished, production model. On the Sunday evening, Glebov plays a brilliant, warping set that reminds me of Underworld under the name Space Holiday Rocks, wearing a black cape and playing machines sat on tin foil. He has no trouble holding his own alongside a fizzing Lorenzo Senni set and Helena Hauff being as wonderfully stern yet funky as she always is.

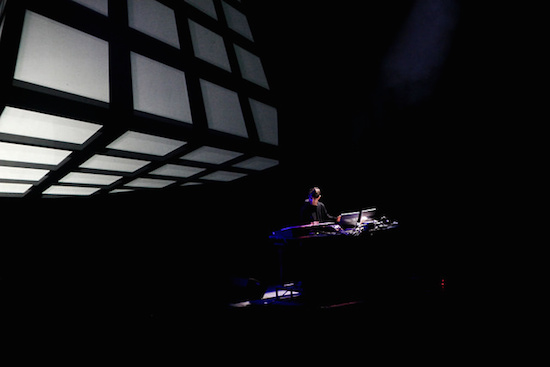

Byetone

One day I will get to see Byetone play at a rave, but for now these seated performances will have to do. Needless to say, I troubled the stability of my seat in the Globus auditorium. The first track, exploded headlights flashing white and grey across the screen, is like an even more austere take on Juan Mendes’ Silent Servant, mechanical and unstoppable, but coldly sensual with it. Yet for all one might like to joke about Raster-Noton music sounding like precision engineered electrical salt mills for a bijou kitchen (the silver tape cover the apple logos on Olaf Bender’s two laptops is just so), the set is all quickly uncoiling groove, and fun with a weird rock & roll element – ‘Black Peace’, from brilliant 2011 LP SyMeta does sound like a techno ‘Hey Mickey’, after all. This is pop brutalism that takes an angle grinder to Daft Punk’s silly helmets, and as giant numbers count upwards on the back of the stage ‘Plastic Star’, completely retooled with a massive bass riff underneath it, thunders forth like digital heavy metal.

Rabih Beaini

This is an absolute collision of music, liquid rumblings, as if the skein of wires that connect all Novosibirsk’s buildings at various heights (I keep tripping over one cable that someone is using to leech a phone connection) had picked up short wave transmissions from across the globe. Uncountable voices, all discussing the weather. He plays what I am imagining must be a field recording of a folk song, the language of which I can’t catch over a hulking bastard of a track, a rhythm by a thousand drums, like the weird chaps on that Mad Max: Fury Road music rig. He keeps pulling that in and out of the mix, then flies into some mind melting jazz drowning in shards of drums, something else that sort of might be The Ex. This is true freak-out music, God’s own record collection falling on your head, and the sounds we’ll be broadcasting to aliens should the peoples of the earth ever decide that they can get along.