Perhaps the most important thing about Bruce Springsteen’s final show in Europe this summer lay in two songs that weren’t played, and one thing that was said. The two songs that weren’t played were ‘No Surrender’, from Born In The USA, and ‘Ghosts’, from 2020’s Letter to You. One or the other of those songs had been played at nearly every show since Springsteen and the E Street Band began this current run of touring last year, frequently as a pairing to open the show.

Last summer, the choice of songs felt very deliberate, both pieces of nostalgia for bandmates and companionship and a romantic dream of what rock music might represent. But the former, written when Springsteen was a young man, carries with it defiance, a sense of having been proved right when everyone else thought he was wrong. Its famous opening lines set its tone: “We busted out of class, had to get away from those fools / We learned more from a three-minute record than we ever learned in school.” Having achieved all he dreamed of, there could be no retreat, no surrender.

‘Ghosts’, though, was released as a single the day before Springsteen turned 71. In this song, too, Springsteen remembers a companion in guitars, but this time the friend is gone, and he is struck by the knowledge that “I’m alive, and I’m out here on my own.” He makes his vows to continue, for himself, out of loyalty to the ghosts that walk by his side. Put the one after the other and the message seemed inescapable: this is what we were, and this is our fate.

Last summer, after seeing three shows – Villa Park, and two in London – I was convinced it was the last time I would see the E Street Band. It wasn’t just that pairing of songs, it was the whole construction of the set. For the first time, the E Street Band weren’t playing a seemingly freewheeling selection from down the years, but a rigid core setlist with the occasional substitution. The setlist was telling a story, and the story was: We are not long for this earth, as people, or as a band. It kept popping up: in the coupling of ‘Last Man Standing’ and ‘Backstreets’, the former a requiem for George Theiss, of his teenage garage band The Castiles, the latter given a monologue in honour of his old factotum and friend Terry Magovern; in the cover of The Commodores’ ‘Nightshift’, a lament for Marvin Gaye and Jackie Wilson. As if to hammer the point home, the final encore has always been I’ll See You in My Dreams: “For death is not the end / I’ll see you in my dreams.”

I still think the original show was conceived as a goodbye. But it has evidently ceased to be that. Introducing ‘Last Man Standing’ at Wembley on Saturday night, Springsteen told his usual story, of how the Castiles lasted three years – pretty good for teenagers – but that the E Street Band had been together 50 years. Then he looked up and added a few extra words: “And we ain’t fucking going nowhere.”

There are bands I love but never need to see more than once on any tour. AC/DC, for example. I love to hear that set once, but given it’s more or less the same set they’ve been playing for 40 years, and I know every one of the songs back to front, I don’t need to hear it twice with an evening in front of the telly separating the shows. But there are also bands I will go to see night after night, knowing I will hear something different and feel something different. I’m no hardcore National fan, but I wished I had been last year, when they played completely different sets on consecutive nights. I go to see The Hold Steady every time I can, watching them over several nights at a time, feeling the mood and the pace change.

It’s not just a case of wanting to recapture the excitement of that greatest ever gig, the one we all hold in our minds as the perfect performance. Nor is it simple fandom, the need to be at every possible performance (though I’ve had that plenty of times in my life), though to go repeatedly, of course, you probably need to be a committed fan. Yet committed fans don’t always get the best end of the deal. The production arms race that is live music means fewer and fewer big shows dare to be unpredictable. When every moment is synchronised by computer – each visual, each lighting change, each pyro – everything has to happen at a precise moment in a precise place. It’s more like watching a musical than a gig. If you get the same thing every night, how do you parse something different from each show? So salutes to those big pop acts with young repeat audiences, who do try to make shows different. Salutes to Taylor Swift for playing her surprise songs every night, and to The 1975, who’ve rotated 70 songs in their current setlist, with only three played every night.

Why do people go to gig after gig? For me, in part, it is the unicorn hunt of the superfan, the desperate hope that you’ll get something special you seldom hear, which both Springsteen and The Hold Steady deliver with rewarding frequency. But more important than the fandom, the being part of something, is the internal: the emotional impact of the forces coming together at that moment in time as the band plays. They are the forces we generate ourselves, from whatever turmoil is within us, and the forces imposed on us by the words and the music we hear, and the forces of the crowd we are part of.

I feel these forces more keenly at Springsteen shows than at any other live performance, despite being – by Springsteen standards – nowhere near a superfan. I crave the emotions I am going to feel when he performs, the sense of joy and release. The euphoria, and the inexplicable tears, of something that might be joy, but might be its inverse. And how I will react, of course, depends on what emotions I bring to each show.

That is why Springsteen has such an effect on me. Because the ambiguity and emotional complexity in his best songs sounds like real life.

It doesn’t matter how much of it is bullshit, and there have always been people who’ve called Springsteen out as a bullshitter. Way back when, John Sinclair, the Detroit countercultural figure, wrote: “Springsteen’s songs are not songs of direct experience compellingly told as acts of cathartic artistic release. They are tales of a mythic urban grease song which, taken together, form a script for a third-rate television treatment of delinquent white youngsters of the slums.” Springsteen himself admits he’s never done a day’s work in his life. All those songs about working? Just made up off the top of his head – but that is the power of art and imagination.

I have no idea if his portrayals of New Jersey working class life are true, but his portrayals of shattered hope and tattered dreams, of self-doubt and self-loathing, of trying to find a spark to light the darkness – those are all true. Those are emotions everyone feels. That’s what Springsteen understands and tries to draw out.

Eight years ago, I interviewed Springsteen and asked about live performance, specifically about what he meant when he referred to the “covenant” between him and his audience depending on honesty. His answer was a marvel, the kind that makes you realise quite how important the act of performing songs to an audience that needs to hear them can be.

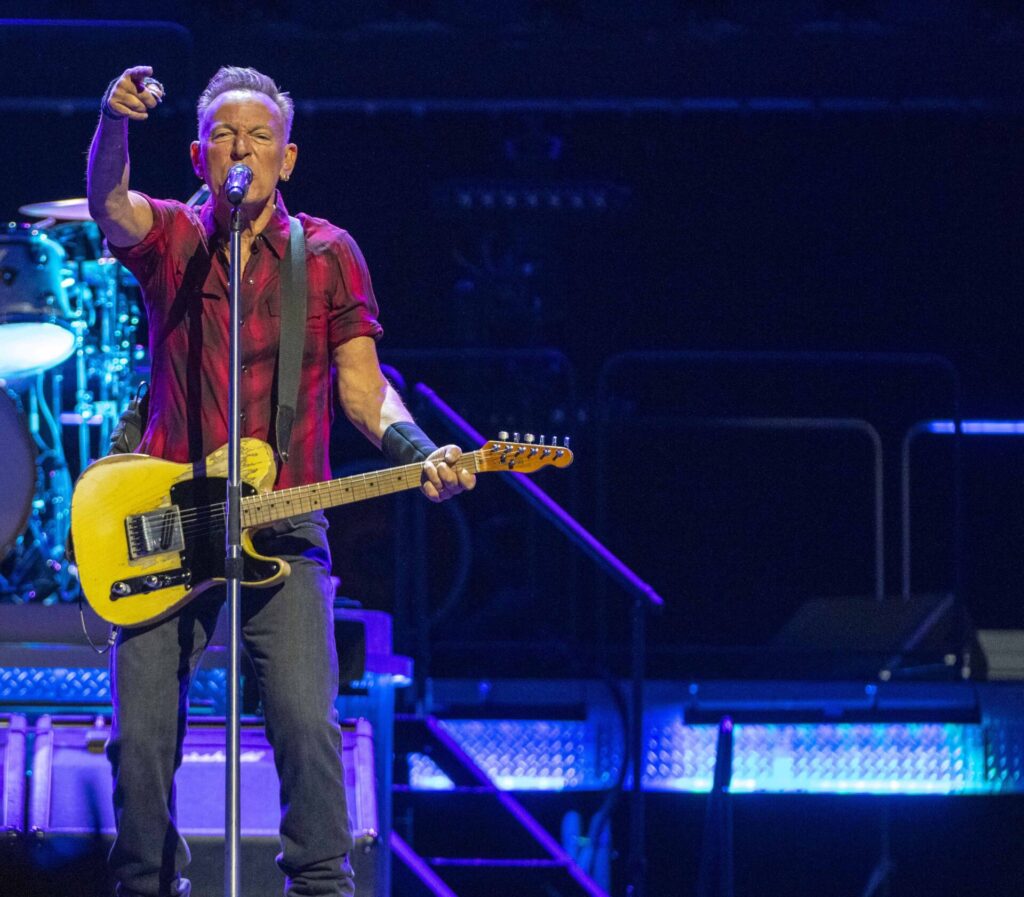

“I guess we come out and deliver the straight dope to our crowd as best we can,’ he said. ‘It’s coming on stage with the idea: OK, well the stakes that are involved this evening are quite high. I don’t know exactly who’s in the crowd. But I know that my life was changed in an instant by something that people thought was purely junk – pop music records. And you can change someone’s life in three minutes with the right song. I still believe that to this day. You can bend the course of their development, what they think is important, of how vital and alive they feel. You can contextualise very, very difficult experiences. Songs are pretty good at that. So all these are the stakes that are laid out on the table when you come out at night. And I still take those stakes seriously after all that time, if not more so now, as the light grows slightly dimmer. I come out believing there’s no tomorrow night, there wasn’t last night, there’s just tonight. And I have built up the skills to be able to provide, under the right conditions, a certain transcendent evening, hopefully an evening you’ll remember when you go home. Not that you’ll just remember it was a good concert, but you’ll remember the possibilities the evening laid out in front of you, as far as where you could take your life, or how you’re thinking about your friends, or your wife or your girlfriend, or your best pal, or your job, your work, what you want to do with your life. These are all things, I believe, that music can accommodate and can provide service in. That’s what we try to deliver.”

Two summers ago, my world exploded. All my own doing. No one else’s fault. And I spent a year trying to rebuild. By last summer, things were good – I was feeling happier than I had for decades. So the three Springsteen shows I saw, with those themes of death and decay, didn’t have the impact I expected. I went in hoping for a reflection of my own joy – joy being the prevailing emotion of an E Street Band show – and while the joy was present, the melancholic tone of the setlist outweighed it. Of course they were wonderful shows, but it was not the precise emotional hit I needed at that time. I needed to think of possibility, not the past.

This year was very different. The first of my three shows was Sunderland, back in May. Six hours of driving with the wipers on full, my 20-year-old son asleep in the front beside me. Long queues to get in, which meant even the people under cover were soaked by the time they took their seats, while the people on the pitch looked dressed for a winter expedition to the Himalayas. The band took to the stage late, all bar Springsteen dressed in as many layers as possible. Springsteen himself was in rough voice, coughing between songs, struggling with high notes.

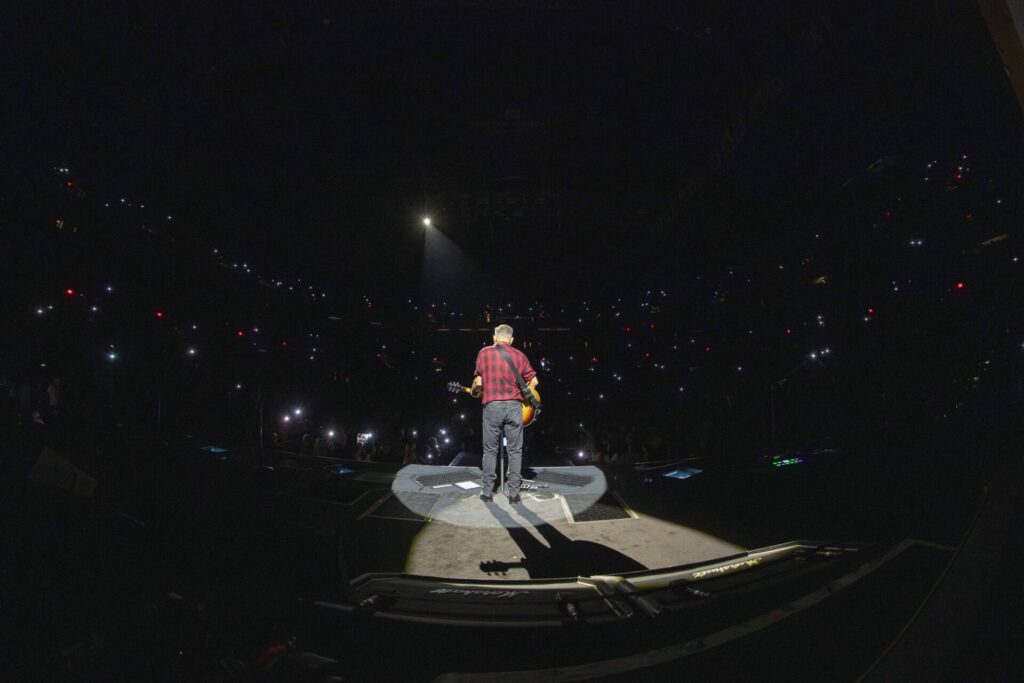

I wonder, had this show been in one of Europe’s sunnier capitals, with pavement cafes and bars and street culture, he might have pulled out. But it was in Sunderland, on a dismal night. And perhaps he thought he couldn’t send 40,000 people who had come for him back out to choose between McDonald’s, a kebab, or quiz night in the pub. He had to work hard that night, and he did, spending large chunks of it prowling the barrier, making sure the crowd were constantly on the big screen, conveying to us that we were all part of this, in the rain and the cold and the wind. That we would find something in this night together. And we did. (The big screens are an important part of a Springsteen show. There are no accompanying visuals, very few wide shots. When Springsteen sings, the camera is close up on his face, always: the purpose is to aid communication, not boost the spectacle.)

After the show, the rain quieted, my son and I sat on a bench on the Sunderland seafront, watching the lighthouse blinking, and a trawler headed out to the North Sea. He shared a joint, and we talked about the world, and went from being fans who’d watched a rock show to a father and son who had shared an experience together.

By the time the first Wembley show rolled around, though, my life felt in ruins again. And never was the truism that what you bring to a show affects your reactions more proven. I’ve written a lot down the years, including for tQ, about the despair that inhabits so many Springsteen songs, and last Thursday night, I felt every line hitting me like a hammer. Looking down the setlist, I see seven songs that had me in floods of tears, and even songs I seldom give thought to were cutting me off at the knees.

‘Reason To Believe’, a sparse, sparse rockabilly from Nebraska, was recast as John Lee Hooker-style blues, backed by a massive R&B band. Its lyric, to me at least, on Thursday at least, was about futility. About people who appear cursed by the hope for something different. “Struck me kinda funny / Seemed kinda funny, sir, to me / How at the end of every hard-earned day people find some reason to believe.| Believe in what? Is faith itself hopeless?

Springsteen was a kid when he wrote ‘Thunder Road’, and marvellous song though it is, he probably didn’t have middle age in mind when he wrote it, but the simple truth of “So you’re scared and you’re thinking that maybe we ain’t that young anymore,” was devastating. I am scared, I am not young anymore. But I can’t get in the car and hit the open road and drive away from it all. At least, not without sitting in traffic on the A1 out of London for hours.

I’ve never felt so completely devastated by a show before. Yes, I could find my joy in it too, but it was a very tempered joy. Time and time again, I had to sit down, my face in my hands, feeling the pain wash out of me. It was not my favourite Springsteen show. It was, entirely unexpectedly, the one I needed. “Lolz at your crying,” said my 24-year-old daughter on the Jubilee line after.

And then Saturday, and the other show I needed. I went into Wembley in a state of mild terror. Would I be in the same state as Thursday? That evening, I had been wretchedly grateful for the songs that weren’t played that would have devastated me – no ‘Tougher Than The Rest’, ‘Darkness On The Edge of Town’ or ‘The River’, thankfully. They all appeared on Saturday’s setlist, but this time I was ready for joy. I was ready to hear those songs not as commentaries on my own failures and frailties but as moments in a much broader, longer and richer life.

I’m not one for comparing show x and show y and deciding which one was better, by any artists. Most bands play stinkers once in a while, most bands play blinders once in a while. But maybe Saturday’s show wasn’t just the one I needed, but a remarkable one: certainly, looking at social media afterwards, there were a lot of long-time Springsteen fans saying it was the best they had seen. There was sense of controlled manic propulsion about it, a markedly different setlist than before, and the sense of death and decay was markedly reduced by the removal of ‘No Surrender’/’Ghosts’.

It’s not that I love every single thing in a Springsteen show. I could cheerfully live without his excursions into the Irish folk-punk idiom. I wish, sometimes, that he might dispense with most of the musicians on stage and take some of the songs as a garage rock band might. I especially think that rockabilly and R&B rave-ups rarely require six different people to take a solo. But, you know, stadium rock and all that.

But no one else and nothing else wrenches these feelings from me. Come the encores, the house lights always come on, and the whole, vast crowd is always bathed in light. Here it is, Springsteen is saying, this show is you and it is me and it is the band, and we are all together under these lights tonight, and we can build something spectacular. As the band went into ‘Dancing In The Dark’, a young woman a little in front of me in the front standing climbed on to her companion’s shoulders, and began going wild. I barely looked at the band, watching her frenzy as she tried to simultaneously dance, act out the lyric with her arms, and balance. I cried watching her, not for grief or fear, but for her embrace of the moment. I cried tears of happiness for her. And as we left, my friend Laura laughed as I danced up the steps from the pitch high-fiving every security guard. My problems had not been cured, but I had been given the sense that hope was not necessarily futile.

None of that would have happened had I gone to only one show. God bless the artists who want us all to feel every emotion.