"Converting all that organic material into human flesh is completely nuts," a physicist ("a theoretical physicist, therefore everyone else has to deal with my bullshit") announces to a room of filmmakers, journalists and members of British Sea Power at the CERN experiment, just outside Geneva.

As well as matter-of-factly explaining to us that simple equation of the imminent crisis of global overpopulation, he has also managed in this brief talk to explain how science fiction is hardly exciting compared to our own reality (when the chair is an anti-gravity device, why bother with the farcical machines concocted by cinema?), how scientists at CERN crash the Large Hadron Collider’s beam into special targets when they go "wild", and why, despite humanity’s parasitic reproduction rates, space colonization won’t save us.

As John Doran wrote in his MENK column for VICE, CERN is that sort of place. While the beam whizzes around 100 metres under the wine-growing topsoil of both France and Switzerland, thousands of scientists and their auxiliary staff work above them. Some, like the Japanese physicist with the crystal bracelet and odd hairs coming out of the underside of his arm, seem decidedly unhinged. All have clearly devoted a substantial proportion of their lives and an intellect that puts most to shame to try and discover these very minutest secrets of science…. though it’s interesting to note that they, more often and not, say not that they’re in quest of some concrete, scientific truth, but to better understand the workings of nature.

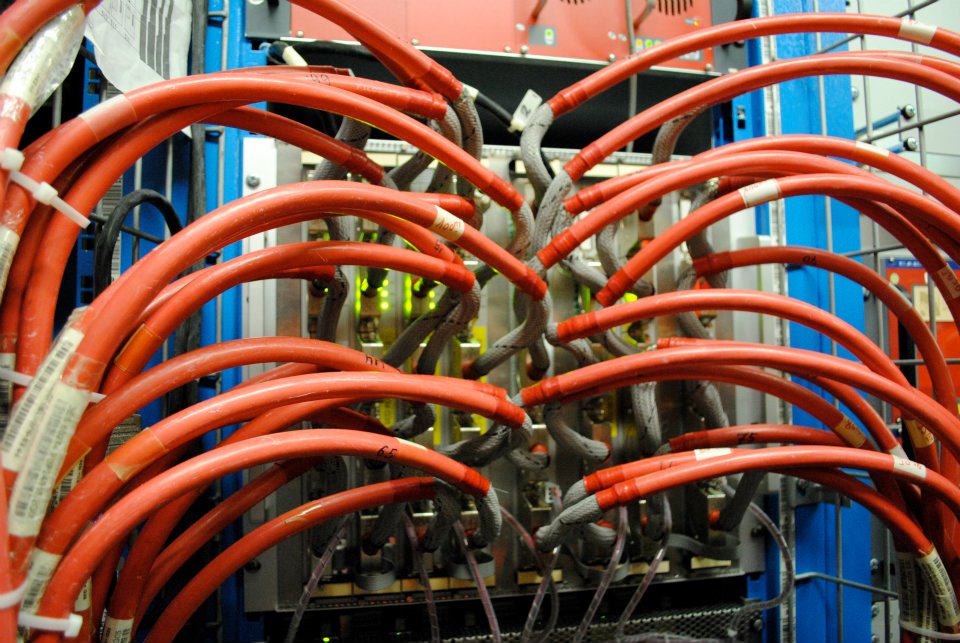

In the experiments themselves, situated like blips around the 27 kilometer circumference of the Collider, the scientists work isolated save for the visitors who come and gawp at them behind their monitors before disappearing into the cavern for a brief glimpse into their world.

Down there, we are told that there are magnetic fields more powerful than that of the earth. Entering the main experiment cavern (we’re just allowed in the service tunnel) would result in an instant, fatal dose of radiation. Opinions seem to differ as to the impact of being hit by the Hadron beam itself, but it generally seems to involve mosquitos with the kinetic energy of aircraft carriers moving at light speed. Still, apparently to fix electronics when they go wrong all that’s needed is a certain amount of pull it out and push it back in again to fix it.

Up on top, 60s buildings contain warrens of corridors lined with uniform brown doors. Behind some of them are terrifying equations scrawled all over blackboards. Some scientists keep their offices entirely minimal. Others are piled with papers, periodicals, ephemera. Oddly they all seem to be pretty clear of technology, as if what goes on in the caverns is quite enough, thank you very much.

Yet the dome-shaped space where British Sea Power perform their soundtrack to 1999 documentary Out Of The Present is a very different place. Sustainably constructed out of wood, massive beams curve up to a circle of blue light at the very top. It feels for all the world like a very contemporary, sacred space.

Out Of The Present tells the story of the crew of the MIR space station over a few monumental months in the early 1990s. The Cosmonauts went into space and to their duties as Soviets… but while they were up there, tanks rolled out onto the streets of Moscow, and they returned to earth as Russians.

British Sea Power, tonight represented by guitarist Martin Noble and Yan Scott Wilkinson, have put together a soundtrack that’s quite a departure from their previous work creating new music to accompany Man Of Aran, the 1934 film that told the story of families living on the wild coastline of Western Ireland. Where that dealt in tumults of guitars and brass to match the rising waves, this deals in sparser, more electronic sounds, with the band happily resisting the temptation to go all-out space rock or Vangelis cliché.

Three people setting off to space in a Soyuz rocket and men heading into the wilds of the Atlantic to spear the basking shark for its valuable oil are of course not as different as might first appear. Humans on a quest, obviously, but both also deal with worlds coming to an end, the fishing traditions that had sustained the western Irish for hundreds of years on one hand, the Soviet system that was about to end after less than a century on the other. And just as performances of Man Of Aran had such huge resonance with the people of the fishing communities of Traena in Norway or St Helier on the Isle Of Jersey, this tale men and women who live and work in narrow tubes filled with wires does seem to connect with this room of women and men of science, even as the scream shows British astronaut Helen Sharman (a post Cold War guest on MIR) floating toward the camera in a pink nightie.

As sweets and letters from their families arrive, so do darker tidings kilometres below. Back on earth, footage of tanks in Moscow streets is accompanied by pensive strings and a beat that suggests imminent action "those are tanks! We are trapped!" the subtitles of a news report read.

Up in space, the human and the humdrum continues. One cosmonaut drinks bubbles of American Coca Cola in front of a poster of a poky little Soviet car. Another uses a ground link to discuss the new furniture (style ‘Julia’) his family has purchased for his home. The astronauts cut each other’s hair, badly, or ride around laughing in zero gravity on large bits of equipment. During one space walk, the cooling system on a survival suit fails prompting a rush back into the airlock. In the most stunning sequence of the film, an experiment to fill a giant back with air fails, leaving a huge expanse of metal flapping in the vacuum, like kitchen foil in a fan oven.

Upon landing, a returning cosmonaut is asked "did you fail to complete any part of the programme?" The response, "of course!"

"Would you like to do another flight?" "I’d love to". such is the spirit of human endeavour. There’s something very right about watching this film, and being at this odd place in Europe, exactly 100 years to the day since the death of Captain Scott in the Antarctic that defeated him.

An acoustic guitar rolls gently, a whistle, a bass pulse as the screen shows an icy landscape passing below.

Never mind Higgs Boson and tiny particles that do things even those who know about them barely even comprehend. What 24 hours at CERN, Out Of The Present and British Sea Power’s soundtrack all bring home is that all-too-often forgotten fact that it is us humans who really are so very small. And yet, whether it’s digging enormous tunnels under Switzerland and France, flying up into space to sit watching as those little things that are our countries come and go, or making amplified rock music, for some reason, we keep buggering on.

"When you took off, the USSR still existed. Your place of birth was called Leningrad, now it is St Petersburg. Which change surprised you most of all?"

The cosmonauts are in front of a flag, not the red banner with its hammer and sickle which they dutifully unfurled upon their arrival, but the Russian red white and blue horizontal tricolor.

"It’s hard to say, so much has happened. Most of all, it was night and now it is light. The seasons pass. That is what impresses me most of all."

The Quietus thanks CERN, the CineGlobe Film Festival, Paul Laycock, Philip Ilson, David Taylor & British Sea Power