When asked, at the end of the 80s, what he thought of Billy Bragg, Ian McCulloch replied that he should stick to love songs and lay off (the state of) England. It is an offhand remark that superficially struck a cord: I sometimes half subscribed to it myself. Having lifted his head above the parapets from the outset, Bragg has always presented a big target (both to the far left, who think his Dorset home is too large, and to the far right who don’t think he should be allowed to live there at all), defining his career by his politics in a way few artists do, laying himself open to a more severe standard of judgement than his contemporaries. Could anyone blame McCulloch for wanting to be entertained and not lectured, or think it unreasonable to prefer ‘Greetings To The New Brunette’ to ‘A Miners Life’?

A reputation for sermonizing didacticism is hard to shake off, but the dichotomy, between politics and the personal was a false one even then. Bragg was adept, from Life’s A Riot With Spy Versus Spy onwards at conflating the two realms, approaching love songs as if they were political, and political lyrics with the ache and longing of romantic balladry. In both types of song his sincerity could be confused for an over literal clumsiness, his honesty for a lack of artistry and his humility for an affectation. Which would be a mistake; Billy Bragg is and was one of the good guys and every bit the equal of more feted songwriters, who hiding behind an apolitical mystique, use their position to say nothing.

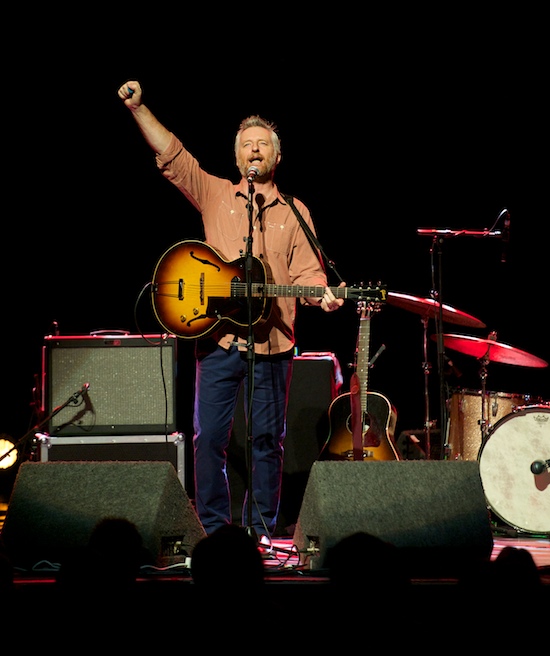

One of the first things his performance tonight dispels is the notion that he’s simply an everyman, or “William Bloke”, drearily reeling off twopenny observations. Watching him in the company of a couple of friends who aren’t fans drives home just how weird, uncommon, deliberate and particular his singing is, and that in many ways he is a genuine original. What “ordinary” singer could have held onto that voice, a lead block of ungiving rigidity, without eventually softening it a touch, or at least, beginning to sing a little more “properly” and polish up their technique? His unashamedly Essex vocal delivery remains musical Marmite, a permanent obstacle to Bragg ever achieving that level of appreciation that would relegate him to the taxidermists shop window that befalls other “national treasures”.

The opener ‘The Clashing of Ideologies’ sounds, with a full band, a closer cousin to ‘The Chimes of Freedom’ than usual, Bragg’s group displaying the same lazy, rickety authority of Dylan’s current outfit. The new album, Tooth And Nail, his strongest since 1991’s Don’t Try This At Home, has been praised for its country and western inflections (Bragg is dressed in a cowboy shirt) and though he laughs at this, claiming “Americana is country music for Johnny Marr fans”, the influence is self evident. ‘No One Knows Anything Any More’, the strongest song on the record, and his second of the evening, has the meditative solemnity of Johnny Cash’s last recordings, showcasing how well Bragg has grown into himself, its themes existential and contemplative. But no song sung by Bragg can remain indebted to the home of the brave for long, his accent doesn’t allow for it, and the new material, like the old, is best thought of as modern English folk; the mix of broken hearts, failing relationships and factory closures, sung from within the culture he belongs to, classic hallmarks of that genre. Politics is as central as ever, ‘There Will Be A Reckoning’ is a recriminative and rousing denouncement of those irresponsible purveyors of extremist propaganda, the Mail newspapers that enjoy a reach, influence and circulation the radical left have yet to match, far less supplant. The song at first sounds like a rallying cry but ends as more of a spooked apprehension.

Throughout the evening Bragg mocks his perceived weaknesses, making an unlikely (until he mentions it whereupon it makes perfect sense) connection to the late Lou Reed. Reed, Bragg rightly contends, gave those who had something to say, but couldn’t “sing”, the confidence to go ahead and try, however atonal the outcome. There the similarity ends, and Bragg cheerfully admits he could have never have written ‘Heroin’ (joking that it would have ended up as ‘Aspirin’), before taking a swig of tea and stating that the wilder shores of experimentation are not his hunting ground. In doing so he risks losing a certain kind of listener, while appealing to an excluded middle; outcasts from the rock & roll aesthetic who are as mystified by the appeal of Metal Machine Music as they are the top forty, but identified with Madness, The Housemartins, and still do with Bragg. Music is full of intrepid spirits prepared to report from the outer limits, but even Sun Ra had to clean his teeth in the morning; Bragg’s songs work precisely because they cover experiences and occupy subjectivities that remain beneath the concerns of many musicians, often sung from perspectives that pour cold water over high ambition, "I don’t want to change the world, I’m not looking for New England, I’m just looking for another girl," still his most famous line.

The glue is his power of empathy, as intense as any musician I’ve heard, the protagonist of ‘Levi Stubbs Tears’ a case in point. Performed tonight in a solo segment in the middle of the show, the song burns, the redemptive refrain so vivid that one believes Bragg witnessed these events, his guitar all edge. The empathy is just as absolute in ‘Between The Wars’, Bragg’s warm voice transforming what could be a singing history lesson into a believably lived experience. It is true that at such times his work can seem two dimensional, though I don’t know if in the context of these songs that is a criticism. Life, at its most intense, often lacks any sense of dimension, and powerful emotions, at their point of collision, feel black and white. If ambiguity has its poets, straightforwardness deserves one too; heartfelt simplicity making up in directness what it lacks in artistry.

Contra to Oscar Wilde’s argument that all art is quite useless, or Auden’s that poetry never made anything happen, Bragg encores with ‘Tank Park Salute’, written over twenty years ago to mark the death of his father. Listening to it then, and over the years, helped prepare me for an event in my own life that I dreaded the arrival of. As time went by, I tried to understand and preempt the bewilderment and incomprehension that lay ahead, to the extent that I felt neither of those things when I finally lost my father, earlier this year. I owe that, in small part, to this song. How a person can prepare for eternity, and the discrepancy between the small corner of the universe we occupy and the larger part we’ll be dispersed into, or not, takes Bragg into territory he is not often given credit for. The song’s tender attention to detail, and exploration of the bigger questions that hang, mostly in silence, over the routine mystery of death, “at the top of the stairs, darkness”, make it the great song of agnosticism, the hope that we can all learn from the loss of someone we love realistic, irrespective of what we think comes next.

There’s enough in-between song chat through the set to provide an evenings entertainment in its own right, and at times Bragg does resemble a politician at hustings, or comedian in a supper club, the cliché that he goes on a bit too much and keeps banging on about politics not far off the mark. But the crowd love it and so do I, his emotional generosity and transparent desire to make the world a better place leaving us with a clearer idea of what it might feel like to be Billy Bragg, a justification, if it was needed, for his three decade stint above the parapets.