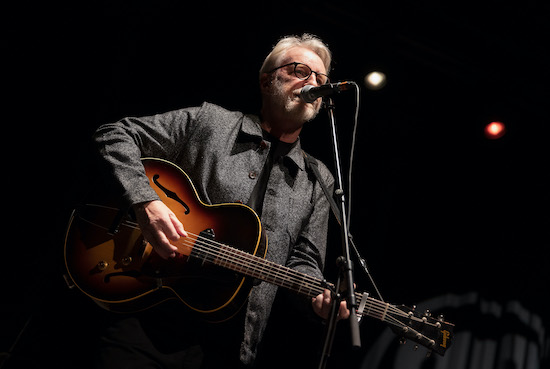

Billy Bragg live in Southend by John Keeble

A vaguely Dickensian setup. A Scrooge-like figure, a man tired of being cynical, is wearily hoping for another chance.

Me: Oh, Billy, is it too late?

Mr Bragg, the Bard of Barking, fixes his gaze at me, nonplussed at first, before cracking into a wide, welcoming grin.

Billy: Not on yer life, son. Not on yer life.

It hits me while walking into the Cliffs Pavilion in Southend, a 1960s venue overlooking the Thames Estuary, that I have no real expectations of this gig. Despite being a dabbler over the years, I have never counted myself as a massive Billy Bragg fan by any stretch. I have nothing against the bloke. I respect him, he’s always been there, and I always agreed with his politics, but, I don’t know, perhaps I have always found the frankness a bit much?

Bragg’s schtick is an easy target. He says what he means. Even quite complex leftist positions are explained in terms that are straight up, guv. I came of age as a teenage music fan in the last years of the 1990s, an era in which the Bard of Barking struggled to connect. As Morrissey enjoyed the status of critical darling through the noughties, before his racism became just that little bit too overt in the 2010s, Bragg seemed the preserve of something perhaps a bit too plain spoken, a bit too obvious, a bit too unreconstructed for the times. A heart-on-sleeve troubadour lost in the boom years of conspicuous consumption.

Bragg would soon be anointed a national treasure (British socialists are either vilified or celebrated to the point of abstraction), but that probably only exacerbated the problem. Commonality in the British popular sphere is often pilloried under the guise of having too little authenticity, a la Damon Albarn’s accentuation of his east London roots as Blur fine-tuned their Cockney swagger down Walthamstow Dogs in the 90s, or too much, as seen in the endless documentation of the Old East End beloved of BBC documentaries, the end point of which was The Last Whites Of The East End, a documentary that asked viewers to try and believe in the idea of ‘a native east Londoner’, despite the churn of diversity that has characterised that side of the city for centuries.

A lot has happened in the years since. The kind of leftism that Bragg has long been a proponent of became a force again in the UK in the years before the pandemic struck. Since the occurrence of this era-defining schism, our lives have become thin scrapings of what they once were. My usual fairly optimistic if admittedly anxiety ridden and cynicism-tinged countenance has been hampered by a life where my kicks come from ever decreasing means.

Tonight Bragg is backed by keyboard player, Thomas Collison; a situation that one heckler deems too fancy later in the gig ("JUST PLAY ON YOUR OWN LIKE YOU USED TO"). He is newly bespectacled and his hair has a kind of floppy sheen. He exudes an easily worn niceness, an amiability. Nothing to peel away, no layers of intrigue, no hidden depths, no secret agendas. This is, perhaps, what irks people about Bragg, of course, the fact that this guy can be so easily read, that his heart is not only on his sleeve but is pulsating in red neon for everyone to see while he delivers the line “Look here is my heart on my sleeve!” in his loudest Estuary delivery.

It’s probably why it’s taken me until I’m 37 years of age, with two kids, living back in Southend, to really, properly, absolutely warm to the geezer. Maybe it felt too obvious before. Perhaps this is what losing one’s edge feels like, and if so, I wish it had happened a bit fucking sooner.

Four songs in Bragg plays the title track from the new LP, ‘The Million Things That Never Happened’, a lament about how the pandemic has stolen potentially life-defining moments. The song makes my wife, Hayley, and I tearful, following the death of her father earlier this year, a pain exacerbated by the lockdown conditions. It comes as a great surprise to both of us and leads to us to talking about her grief and our shared grief during the interval and after the gig, for the first time in months.

There is music and then there is song, a mix of rhythm, melody and narrative with its own rules of magic. Perhaps it’s the times, but more and more of late, I have come to embrace the skill of songwriting as a transformative device, to transport me to a place, to an emotion, to unfamiliar territory via empathetic bridges of melody. Bragg refers to himself as a “topical songwriter”, which is perhaps more meaningful to his own process than us as consumers of the results. A few years down the line some of the older numbers aren’t just harking back to a time. They’re alive. ‘The Milkman Of Human Kindness’ – who writes a song like that? An unabashed celebration of being nice. Or ‘A Lover Sings’, a song that directly describes the art of falling in love, the song he opens with. It’s easy, but not too easy. It’s all good.

With a few scratches of the guitar some in the audience join in with the first line:

"With the money from her accident she bought herself a mobile home."

‘Levi Stubbs’ Tears’ is a knockout. A song about a woman who soothes her trauma by listening to the Four Tops, which uses the loneliness of the imagined protagonist to teach us something about music. Something beautiful, about its transformative power, and the fact that this power is needed. A song stripped back as far as it could go, just him and his scratchy Telecaster; Young Marble Giants without the archness. Apparently one of Bragg’s great experiences was his discovery of the Four Tops early in adolescence. The protagonist patches up the wounds of her pain:

"Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong

Are here to make everything right that’s wrong

Holland and Holland and Lamont Dozier too

Are here to make it all okay with you"

What I’d never realised about Bragg until tonight is that he is a soul singer, really, and in the past soul music offered a means of self-expression to the British working class; a way of articulacy; a way of reaching out and up and over their obstacles, from Wigan Casino to the Goldmine on Canvey. There is something about soul music and R&B and Estuary Essex. The pirate radio stations transmitting from the mouth of the Thames, such as Radio Caroline, brought soul music to teenage bedrooms. The nightclubs and the karaoke. We have laughed about little bald men like Phil Collins doing Motown for other little bald men to groove to but the roots of the kinship between caucasian geezers in dormitory towns and the music of emancipation are filled with feeling and emotion and allyship.

My own first experience of music was being dragged around the bars and clubs of Essex with my dad as he set up for gigs while Mum worked her Saturday shift cleaning Southend hospital. Dad started a soul band with some teachers at his school, including the singer Everett, one of the first Black people I had ever met in White old Essex. Dad, the art teacher at a school in Basildon, played bass, a young English teacher called Stuart played lead guitar, a brickie mate of theirs Peter played sax and they toured local function rooms so the Saturday night glad-rag crowd could boogie. It was over the road from the Cliffs Pavilion, at Westcliff Hotel, where, during a soundcheck run through ‘Mustang Sally’, that I really started to think that music was worth something; a nine-year-old enchanted by Everett’s scratchy, impassioned impression of Wilson Pickett as disinterested bar staff stacked glasses.

Billy Bragg live in Southend by John Keeble

Bragg is fresh from playing Brighton, where the crowd was probably more safely in tune with his left-liberal, approachably socialist schtick – but back here in Essex, it feels like he might have work to do. He seems aware that mask-wearing is more of a contested thing here (he tells us that the venue in Brighton wanted a lateral flow test from each audience member, but tonight they realise that "nobody gives a fuck in Southend"). But what is evident from the equal amounts of cheering that greet the sentiments of "West Ham United" and "socialism", there are still a lot of people in Essex who don’t wake up every morning and sink prostrate in front of their Thatcher shrine before firing up Twitter to row with the wokes.

Before the gig, Bragg had caused a mild ripple in the great Culture War pool by changing a line his thrilling late 80s hit ‘Sexuality’, from from “Just because you’re gay, I won’t turn you away. If you stick around, I’m sure that we can find some common ground” to “Just because you’re they, I won’t turn you away. If you stick around, I’m sure that we can find the right pronoun.” He explains on stage in Southend with a plain logic that the front line for allyship has shifted from gay people to trans since the 90s. There is some annoyance from a woman who has become Chief Heckler, urging him to "GET ON WITH IT!" Bragg acknowledges that some feminists who fought hard for women’s rights in decades past might find it hard, but explains the plight of trans women with a plain logic that wins most over. When the same woman heckles again during a Bragg oratory on the idea of ’empathy’ in the age of polarisation and echo chambers, he was incredulous: "How do you try and shutdown a rap about empathy? Have you been to a Billy Bragg show?" But by this point the rest of the hall is onside.

The gig is quite revealing in terms of how the modern polarised landscape can be dealt with. Judging by the trajectory from 80s leftism to the current ‘question everything’ trend of scattergun scepticism, a portion of his fans are in a different political camp to him these days, and he knows it. His attempts to win some of them over between songs don’t involve shouting them down. Instead he implores them to think again, promoting a renewed urgency over climate and foregrounding fellowship without ever preaching or seeking to create a sort of toxic at-all-costs solidarity. He just asks people to think a bit harder while they enjoy themselves. He opens up the thinness of the current moment, and seeks to explore subjects such as online obsession and reintroduce notions of kindness and communion into a discourse that has swapped them for divisive sloganeering. And the man’s wit is whip smart. When a bloke who’s had one too many proclaims "I love you Billy!" the singer-songwriter quickly replies: “I thought I told you to wait in the car.”

Towards the end of the set, there is a hankering after a song that most round here identify as their own. The gig’s subtext is a quasi ‘homecoming gig’, as Bragg is the writer of Essex Anthem, ‘A13 Trunk Road To The Sea’.

"If you ever have to go to Shoeburyness

Take the A road, the okay road that’s the best

Go motorin’ on the A13"

Bragg wrote it in 1977, when he was singing in his old punk act, Riff Raff. "I just objected to singing about these places that I didn’t know," he said in 2006. "I wanted to put the A13 on level pegging with Route 66, as there’s a tradition of driving down the A13 to the glory of Southend. Growing up in Barking, that was the promised land, in quite a Springsteenish way. Later, when I saw where Springsteen is from, the New Jersey Turnpike, it did look a lot like Essex."

The A13 is fringed by the sublime violence of modern life. Docks, shipbuilding, brickworks, demolition companies, waste disposal. When Bragg was a kid his connection to the river was total, but power was soon transferred to the ever-widening road. The East End erupted and spewed out housing across Essex. The area of south Essex from Bragg’s Barking to my Southend, at ‘the end’ of the A13, was built in a flash of aspiration and need, emanating from the industrialised slums of the East End and out. Implicit in the boom of plotland bungalows and terraced houses was the rise of socialism in the Labour party, and the desire for ‘Land Nationalisation’, a late 19th century cause that sought to lift working classes out of a life lived under the whim of their landlords, with almost all UK residents renting their dwellings at the turn of the 20th Century. That this fit of socialist thinking ends up with Thatcherite home ownership and Right to Buy is one of the great ironies of south Essex. In this big mid-century hall in Southend, Bragg’s kinship with a swath of mortgaged Essex reminds us that we don’t live in a land solely of atomised gammons hellbent on voting Tory blindly until the country is a burned out husk.

The last couple of years have turned some aspects of life into remnants. We need a route out from the narrowness of our times and in a venue overlooking a chilly Thames Estuary, its fairgrounds and casinos, it feels like Bragg is offering it.