Pictures courtesy of Francesca Sara Cauli

It’s three o’clock on the beach at Hana Bi and the customary Italian riposo explains, I think, why Kat Bjelland is unavailable for interview. It’s nearly thirty degrees. At home in Minneapolis it’s eight in the morning. She’ll pick up on things after a sandy soundcheck but in the meantime Maureen Herman and Lori Barbero are handling Italian press outside their hotel in Ravenna. They’re dodging mosquitoes and submitting to enquiries that seem to boil down to one question, the one so frequently-asked it became the title of Kim Gordon’s tremendous memoir: "What’s it like to be a girl in a band?"

“Man,” says Barbero, happily exasperated. “I really prefer personal instead of generic. ‘How did you get your name?’ They don’t ask that any more but Jesus Christ… that’s shit that you can fucking look up. It’s already been said and done forever.”

“We’ve had some good interviews,” says Herman, settling down to a table indoors. “But one guy from overseas hung up on me! He wanted a specific answer he wasn’t getting, about ‘girl bands’. When somebody’s already written something in their head they only want quotes to prove their points. The reader doesn’t want to see the same thing over and over again.”

Herman’s appreciation for the reader comes as much from her years spent working in journalism as it does from an allergy to seeing bands categorized according to genitalia. Since last playing with Babes In Toyland in 1996 her energy has been devoted to writing, working in music technology and raising her twelve-year-old daughter who was conceived – to write as candidly as Herman has – in the midst of alcoholism, crack addiction and near-homelessness following a robbery and gang rape.

That’s a story for another time, specifically July 2016 when her first book It’s a Memoir, Motherfucker is published by MacMillan.

In the meantime the reunion that brings Babes In Toyland to the Italian coast is part of an ongoing process of renewal and mending for all three members. A fluctuating assortment of drink, drug and dependency issues went madly untreated during the big alternative rock boom of the 1990s, and they’ve had to get to know one another again. Barbero and Herman have always had a good rapport. They started talking again shortly before Barbero moved back to Minneapolis after working for South By Southwest in Austin, Texas.

“I had my daughter by then,” says Herman. “We were talking about that, just kind of catching up. There wasn’t all this baggage. For me, anyway. But I was a big drunk back then. With Kat, she and I actually got closer. We shared stuff that brought us into a similar mindset. It’s a good combination. It was easy.”

“It really was,” says Barbero. “Even after twelve or fourteen years of not being with each other and living in different cities. We’re just more mature. And that’s the great thing about maturing: we’re mentally healthier. I mean, we’ve been through a lot.”

They say that speaking clearly and being direct helps, though when I use the word ‘huffing’ I have to clarify that it means sulking and not sniffing glue or gas. “In the past there’d be resentment and hiding, yeah,” says Herman. “Now we have the communication skills. If something comes up, just talk about it. Which doesn’t mean it’s easy, but there are ways through.”

“When I was younger I thought I was healthy,” says Barbero. “But I look back and see that I really wasn’t. My dad always told me to shut up. So that’s what I always did. And I built up a lot of animosity and anger. Now I’ve learned how to not shut up and I’ve learned how to take care of myself and take care of my relationships. I’ve learned how to communicate. I’ve learned to speak up. That’s for everything, not just Babes In Toyland. My family, my boyfriend – it takes a lot of work to make things work!”

When things worked for Babes In Toyland they worked very well. Barbero remembers that gigs at The Pyramid in New York which resulted in two great opportunities: being spotted by their fondly-remembered A&R man Tim Carr, and being asked by Thurston Moore to go to Europe on the tour filmed for 1991: The Year Punk Broke. “Those two things are the biggest things that happened to Babes,” she says. They were also careful to work within their means. When they began appearing on MTV the economics and culture of the channel had been altered radically by the video for Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’, a flaming arrow from the American underground that burned up the six-figure budgets and stylized pomp of videos by Poison or MC Hammer. At £25,000 the video for ‘Teen Spirit’ was considered inexpensive but finished with director Sam Bayer, selected by Geffen, being kicked off his own edit. Babes In Toyland insisted on working with people they knew, enabled by the 100% artistic control clause they stipulated before signing to Reprise. In 1995 the video for ‘Sweet ’69’, directed by Barbero’s one-time roommate Phil Harder, was delivered to MTV for $5,000 becoming one of the least expensive clips ever broadcast on the channel.

At Beaches Brew many Babes In Toyland fans are amazed that they can see the band in such close quarters and that they’re so accessible. Overall the scale of the line-up exceeds the scale of the event in the best way. More than a dozen bands come straight from Primavera in Barcelona – Shabazz Palaces, Mdou Moctar, Viet Cong – and perform completely free of charge by the ocean or up at Ravenna’s marina. The industrial techno of Stromboli and the searing guitars of His Electro Blue Voice, both from Bologna label Maple Death, are worth the price of free admission alone.

If there’s a cost it’s the mosquitoes that seem to have mistaken the music festival for a culinary festival, emerging at sundown to siphon blood and spread poison without any regard for the musicians. When Ex Hex play, Mary Timony has to squint against bugs darting round her eyes. But if there’s an upshot it’s visual: fans clapping and slapping themselves like they’re in the latter half of an Arkansas barn dance.

After Babes In Toyland soundcheck a DJ plays the Space Lady while Kat Bjelland marches across the sand in tall black boots, stopping for chats, standing shoulder to shoulder with fans for smartphone photographs. People have come from across Italy to see them play. There are a smattering of fans from the UK and even a couple from Bulgaria who asked Barbero to recommend bands from Minneapolis.

“I made a diverse little list,” she says. “Noise guitar bands, pop bands, indie rock bands. I love Gay Witch Abortion. They’re really great.”

Minneapolis is relatively supportive of musicians, writers and artists, a place where creative effort is taken seriously. The innocence of the 1980s music scene became tainted by heroin but it’s still the city that gave The Replacements their start and the city where Hüsker Dü independently produced their first single ‘Status’. Barbero speaks fondly of Prince and Soul Asylum, remembering that she once met Mo Tucker, one of her own musical heroes, on the west bank by the University of Minnesota. “There’s one female drummer older than me! I met her at the 400 Bar, which is now closed. In the 60s and 70s a lot of the hippies would have hung out in the area. That’s where Bob Dylan started his career.”

While Toyland’s career hasn’t been subject to the kind of corporate meddling that saw other bands being told where to go and what to wear, it wasn’t as lucrative as you might suppose and led to the predictable difficulties with classification experienced by any group that sets off on their own path. They weren’t part of the Seattle scene or the post-Nirvana feeding frenzy although an early Sub Pop poster had them billed, perhaps distastefully, as ‘Premenstrual Grunge From Minneapolis’. When the New York Times took notice they went with ‘ugly, crunching post-punk’.

They remain unaffiliated to the ‘Riot Grrrl’ bands that began in Washington, although even today fans bracket them alongside Sleater-Kinney and Bikini Kill who formed after them. Some Italian fans muse that with L7 also on tour there’s a ‘90s girl band’ comeback or that we’re in the midst of a grunge revival. In London, Babes In Toyland played on the same night as Kathleen Hanna’s latest band The Julie Ruin. In Glasgow, the same night as Mudhoney. Herman and Barbero dismiss this as simple coincidence. Good bands are always going to want to play. And, as Bjelland has been saying since 1989, “Girls have been doing things for quite a long time.”

Herman says that by focusing on the band’s style and gender, journalists overlook the fact that Bjelland is simply a great writer and player. “I read mail and messages from people who are talking about how the songs affect them emotionally,” she says. “They’re connecting with Kat as an artist first. Same with Patti Smith: it’s talent, not gender.”

This is certainly the case for a fan named James from Croydon, who’s now seven shows into the tour. His buddy Mo had to abandon the pilgrimage after going to concerts in Bristol, Southampton, Manchester, London and Glasgow.

“For me it’s just nice to listen to something that’s genuine,” he says. “The emotions are real. I love the metaphors as well, which are kind of mixed-up and surreal. I find it quite fascinating. Obviously they’re going to be pigeonholed, but they just do their thing.”

His favourite song is ‘Catatonic’, recorded with John Loder of Southern Records for the 1991 EP To Mother. They haven’t played it yet and his money’s running out but his in-for-a-penny attitude means he’s considering taking the train from Bologna for the Milan show the next day, and then perhaps even to Primavera in Portugal.

“I’m trying to figure out whether I can afford it,” he says. “But for me it’s a lot deeper than the music. Kat made me pick up a guitar 23 years ago. She showed me that anyone could do it. She’s my favourite musician in the world. That’s the inspiration: making me want to go down my own path as well. I’ve never actually mentioned that.”

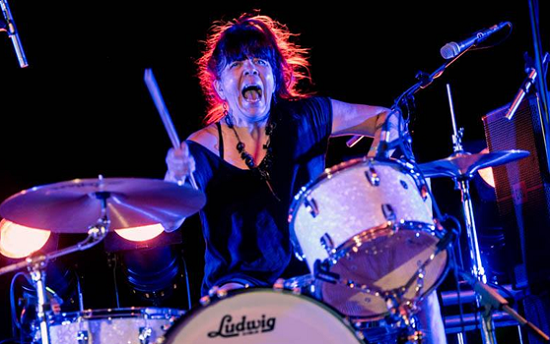

The band don’t play ‘Catatonic’ but Herman and Barbero say the old favourites have retained their resonance. They’re right. From the stage they see a crowd waiting under a full moon above the Adriatic Sea, a crowd jubilant with applause after opening song ‘Right Now’, which twists a bedtime prayer into a defiant screech against death. ‘Bruise Violet’ is still thrilling and dissident, while ‘He’s My Thing’ shows Bjelland’s wild vocal range and Barbero’s tumbling, thrashing drums. She plays with the thick end of the sticks, throwing herself into the kit every four bars like a jockey willing a horse ahead of the pack. ‘Sweet ’69’ sends groups of guys into hypnotic rock trances, girls shimmying and raising their arms in a cross between doo-wop dancing and a Mexican Wave.

Their last song is their first 7” single ‘Dust Cake Boy’, a frantic depiction of a relationship between a boy and a girl ‘with a crystalline cunt made of mint julep tea’. After the finale the people on the beach shout for more but others have run around to the back to meet the band between the stage and small sand dunes. For a quarter of an hour they sign old photos, spiral-bound notebooks, pose for pictures. People trade stories and couples sing lines like, "He is a stupid man – I love him all I can." Bjelland’s lyrics are rarely – if ever – written from a victim’s point of view. She stands tall on a sandy ledge surrounded by a dozen people. I clamber up to interrupt for quote, but stop and just watch until the stage lights are switched off.

Babes in Toyland played at the Beaches Brew festival in Ravenna, Italy. Their tour continues across America and Canada in August, September, October and November