It took a long time to work out what it is that I love about AC/DC but it was at the end of my estrangement with the band that it finally hit home. Highway To Hell may well have been the first album that I ever bought with saved up pocket money, and Back In Black was snapped up on the day of release for the princely sum of £3.49 in Our Price Records in Slough. We lost touch with each other during the 80s, a decade that showed little kindness to many of the bands and artists whose origins were rooted before that decade, but we’d occasionally pass nods of recognition to each other when the odd flash of brilliance such as ‘Heatseeker’ or ‘Thunderstruck’ would fire itself across the bows but it wasn’t until the mid-90s that our relationship was re-kindled.

Fast forward to 1995: I’m living in New York and as is customary on any given Saturday afternoon, I find myself perusing through the racks of the record stores that are located on St Mark’s Place at Second Avenue. Electronic music is floating my boat at that point and most weekends I can be found on the dancefloors of mixed clubs such as Twilo or revelling in the after-hours debauchery of Robots on Avenue B. I’m relying on friends from the UK to send me mix tapes and cassettes of albums that often won’t be released – if at all – until months after they’ve seen the light of day in Europe. Even so, there’s an almost Pavlovian response the moment those chopping and rhythmic chords come floating out of the store’s PA which are quickly followed by sustained notes on lead guitar and a pounding of the toms that gave way to a 4/4 beat. It starts with some inane grinning and within seconds my head is bobbing back and forth like a Saudi drilling pump and the words, "Riding on the highway, going to a show…" tumble involuntarily from my lips. And for the first time in a long time, it feels good. It felt like home. So much so that by the time the bagpipes appear I’m at the counter paying for everything from High Voltage to For Those About To Rock.

And it’s at that point that it hits me about what I love about AC/DC: the rhythm, for here is a band that rolls as much as it rocks.

In Malcolm Young, Cliff Williams and Phil Rudd, AC/DC possessed the tightest rock rhythm section that’s ever locked into a groove. It’s probably why 1978’s criminally under-rated Powerage album remains this writer’s favourite AC/DC album. This is a record fuelled by hunger, a hunger for something better that’s reflected in the best lyrics that their late singer Bon Scott committed to posterity: the frustration of poverty in ‘Down Payment Blues’ (“Get my self a steady job / Some responsibility / Can’t even feed my cat / On social security”), the horror of drug addiction (“I stirred my coffee with the same spoon”) and the aspiration of fast money at the heart of ‘Sin City’ ("I got a burnin’ feelin’ / Deep inside of me”). Yet despite the almost bleak yearning of Scott’s gutter poetry, the album is driven by the murderous rhythm section that’s aimed squarely at the feet while freeing up Angus Young to deliver some of his finest lead guitar playing.

And like Powerage, the rhythmic qualities of AC/DC are frequently overlooked. The playing of the engine room has always been simple, direct and economic. It may well be easy to imitate, but their ability to innovate marks them down as one of the greats. Crucially, this is music you can dance to. For sure, the headbangers have had their way for decades but the indisputable fact is that, like all the best rock & roll, this music aimed for the neck down. In some respects, the music of AC/DC operates in the same way as the best Northern Soul records: just check the 4/4 beats, the bass guitar holding down the root note and the rhythm guitar keeping its foot on the gas. You’d do well to talc the floor when playing this stuff.

Yet this begs an important question: with Malcolm Young out of the frame suffering from dementia and drummer Phil Rudd facing sentencing for drug possession and, more seriously, threatening to kill someone, what will this juggernaut sound like with two thirds of its powerhouse out of commission?

The solution for the AC/DC machine has been relatively simple. Never the most sentimental of people, they are nonetheless canny. Chris Slade, who served five years with band in the early 90s and played on ‘The Razor’s Edge’ album finds himself behind the traps once more while Angus Young’s nephew, Stevie, steps into the breach once more, having deputised for an indisposed Malcolm back in the 1980s. It’s a move worthy of Kraftwerk – machines serving the music – but it also means that the responsibility of leading the band falls more on Angus Young’s shoulders. You always got the feeling that Malcolm Young led from the back. His steely glare throughout shows always meant that the band was performing to his exact specifications as much as they were for the audience.

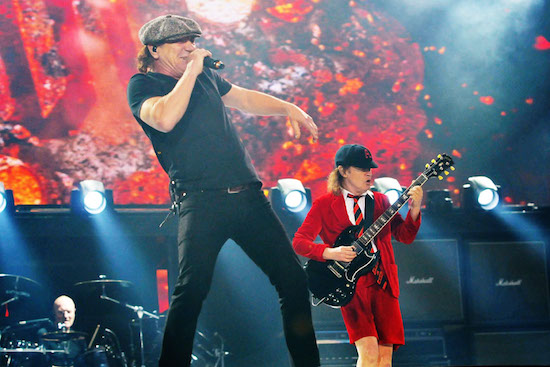

The love for AC/DC is palpable throughout the stadium and the moment the band hit the stage among a series of detonations in front of the monitors, the crowd erupts in a frenzy of delirium that sees pint pots flying through the air, two-finger devil horn signs reaching out and air guitars being played as they leap up and down in unison. It’s a gloriously absurd moment and one that sees much laughter, cheers and whoops being emitted almost involuntarily. And all this for ‘Rock Or Bust’, no less, the opening track of their latest album with the same name. Nonetheless, it becomes rapidly apparent that Angus Young, now 60-years-old, is playing and performing harder than he’s ever done before. He’s never been one to stand still but tonight Young covers every inch of available space in twice the time he used to.

And he’s not the only schoolboy in the stadium. All around, crafty fags are being puffed at a furious rate by smokers keen not to get caught and told off by security. Perhaps it’s that same habit that’s now wreaking havoc on Brian Johnson’s high-pitched rasp. At times it feels as if the singer is genuinely struggling to hit some of those higher notes and such is the effort to achieve them that you can picture him sucking his black jeans up his arse making the effort. Amazingly, he fluffs his cue for ‘Shoot To Thrill’ as he comes in too early and reaches the chorus before the rest of the band does. One suspects that Malcolm’s absence must’ve elicited a sigh of relief from the frontman. Still, what with this being only the second song and the soundman still struggling to make some sense of the stadium’s horrendous acoustics, all is quickly forgiven.

And what of the new rhythm section? Though Stevie Young lacks his uncle’s commanding presence, and Chris Slade’s tendency to speed up, the pair connect with Williams well enough and it’s difficult to shake the feeling that the bassist is driving things along. And why not? He’s been keeping the low-end rumbling for long enough now and by the time the band arrives at ‘Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap’, the sound is under control and the band in full flow.

Of course, half of the set is made up of the Bon Scott era and the band dips into Back In Black five times but ‘Thunderstruck’ is one of those latter day moments that stands proudly with the best of their material.

For a band rooted in blue collar heterosexuality, there’s always been a sense of camp about AC/DC that no one really talks about – just check the way Brian Johnson minces across the stage like an ageing drag queen with Angus Young now resembling a headmaster dressing up as one of his pupils in his spare time behind firmly closed doors. And this is no bad thing; this is simply another component of what makes AC/DC such good fun, albeit one created by accident rather than design. Another joyful aspect is Young’s endless reserves of energy. At times, his feet patter ever faster on the spot as if he’s drawing energy from the national grid and the vibrations move up his legs, through his torso and to the ends of fingers that play one explosive riff after another before revving off on another series of duck walks from one end of the stage to the other. Though they drop a major bollock in the form of the instantly forgettable ‘Baptism By Fire’, they soon redeem themselves in the deep cut one-two of ‘Sin City’ and ‘Shot Down In Flames’.

AC/DC has never been a maudlin band. Not for them any celebrations or acknowledgements of 2015 being the 35th anniversary of Back In Black and the passing of Bon Scott but the feeling remains that AC/DC is tacitly saying goodbye. The video on the screens that accompanies a truly epic – perhaps too epic – reading of ‘Let There Be Rock’ sees computer generated band milestones – the Bon Scott statue located in Fremantle, Hell’s bell, Rosie and so on – and it acts as a summation of all they’ve done and achieved. And none of them are getting any younger, which probably explains why Johnson no longer swings on the bell that’s lowered down for the ever-magnificent ‘Hell’s Bells’.

As the cannons roar their 21-gun salute at the climax of customary encore ‘For Those About To Rock (We Salute You)’, there are some sad smiles among the wide-eyed faces roaring their approval at the end of this two-hour, few-frills-all-thrills extravaganza. This is the same feeling that you find at the end of late night lock-in down your local; a terrific evening spent in the company of close friends despite a few bumps and disagreements, but the call of the world and its unavoidable realities will always prove impossible to ignore. But hey, we’ll always have tonight and all those other nights.

Rock or bust? Still rocking, but probably for the last time. Cheers, lads – have a drink on me.