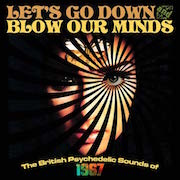

I had to admit, I almost wanted to hope for more given the title of this box set, since the opening song ‘Toyland’ by the Alan Bown! starts off with just that lyric. Except then said line concludes “in Toyland,” having already been preceded by a tape of children playing, and the following line is “Things down there aren’t quite so square,” and have I mentioned the slightly goony flute yet? But that’s what makes Let’s Go Down And Blow Our Minds: The British Psychedelic Sounds of 1967 exactly what it is — it’s not a dreamed-of vision of acid-melting moments front to back, it’s all the possible variations instead.

It’s important to realise where this set fits in in wider contexts. Beyond its contents, it’s the latest example of both Cherry Red’s now near-jawdropping series of multidisc sets focused in on particular scenes and times in pop/rock history. But that itself is a further reflection of the transformation of the industry overall, where extensive box sets packaging a slew of albums by an artist for cheap is now increasingly a rule versus an exception — whether it’s rock and roll, metal, funk, jazz or much more besides, they’re out there in almost infinite numbers. (Speaking for myself, for instance, I hadn’t realised that Siouxsie and the Banshees’ back catalog had gone that route until I saw said sets earlier in a record store on the day I wrote this review.)

Further, this is at least the third Cherry Red-related set in recent years — if not more — that concentrates on the British psych scene in the late sixties. There was the Love, Poetry and Revolution set from a couple of years back that I reviewed for the Quietus, then there was the I’m A Freak, Baby… set from earlier this year. There’s band overlap more than song overlap all over the place, so the net effect is almost to feel like you’re building up a series of intertwined band overviews without realising it — no bad thing, really, but sometimes the individual focus of each set can get lost as a result.

Yet with these caveats in mind, the specific focus of this set — British psych or psychedelic-tinged efforts from 1967, from the start of the year to the end — provides a structure, artificial but useful, for the affair. At the same time, as David Wells readily talks about in his once-again extensive and enjoyable liner notes for such a comp, the big smash acts of the time are either left out or represented by less well-known numbers — my own favorite being the Crazy World of Arthur Brown’s pretty barmy and none more London hippie goof ‘Give Him a Flower’, because “Fire” it ain’t. It’s not a new issue for these kind of boxes, though it is always odd to think of a set like this without anything from Pink Floyd, the Beatles, Cream and, thanks to his relocation, Jimi Hendrix, to name just four. In many ways this is a box set of chancers, most of which would happily own up to the description — bands and performers who had already been around one way or another, trying to figure out just exactly where to go next as sounds and styles shifted around them.

All of which sounds like I’m here to trash this set — but that’s not the case: it’s really lovely with many standout moments, a number of which have long been famous among collectors of the era and which get some new and well-deserved shine here. It’s almost something you need to take a little at a time to appreciate to the full, though — at plenty of points there’s a flattening effect where, even while everyone’s trying to do something to be just that little more weird or unusual, it all ends up sounding at points like the same band doing slightly different things one after another. The uniformity is partially driven by lyric and vocal approaches that often aim towards a general midrange of sweetly hazy trippiness and sometimes by the music balancing out polite r’n’b moves with trying to just stretch out a little more here and there.

So this makes the moments that do break the mold all the more enticing, and gives a sense of what exactly could be done in those moments of inspiration. Hearing the Pretty Things’ initial moment of late sixties transformation with the full-length ‘Deflecting Grey’ in all its crazed tempo-shifting glory is always a treat, while Don Craine’s New Downliners Sect kept up his garagey ways with a cover of the Remains’ ‘I Can’t Get Away From You’. Dantalian’s Chariot, the work of Zoot Money reinventing himself following his earlier r’n’b days, combined his rougher voiced grit with some sharp musical and production moves on ‘The Madman Running Through the Fields’, which is almost too perfect a title. The Mickey Finn’s rampaging ‘Time To Start Loving You’ is an even more swaggering stomp in comparison — the bridge from verse to chorus each time couldn’t sound better — while One In a Million’s ‘Double Sight’ and Jade Hexagram’s ‘Great Shadowy Strange’ also kick up the energy levels just right. One of the more engaging surprises is the snarling guitar kick of Hat & Tie’s ‘Finding It Rough’, which sounds like it could have been from a later era, and not only features a compelling vocal from Patrick Campbell-Lyons, later of Nirvana (not that one, the late 1960s one) but engaging bass work from Chris Thomas, a year out from helping George Martin on The White Album and looking ahead to his own high profile production career. Meantime, hearing Big Jim Sullivan test out his newly learned sitar skills on a song called ‘Flower Power’ — well, what else to add?

Meanwhile, the moments of goofy sunshine pop and/or ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’-inspired freakouts and novelty songs and odd bits and the like that became a part and parcel of what psychedelia was seen to be, at least at the time, play out throughout the set. (Favorite song title, about a breakup: the Secrets’ ‘I Think I Need the Cash’.) Songs like Sweet Feeling’s ‘All So Long Ago’ and the Honeybus’s ‘Delighted to See You’ seem to exist to soundtrack film clips of people swinging along in the streets without a care in the world, presumably dressed to the 1967 nines. (Then there’s the Marmalade’s jangle-on-top-of-jangle ‘Laughing Man’ — which goes a bit laughing gnome towards the end — and the massed harmonies of the Flower Pot Men, whose ‘A Walk In the Sky’ has a line about how the trees have chocolate bars, why because of course.) One early entry, ‘Lazy Man’ by the Mirage, doesn’t even bother to hide how obviously it wants to be ‘Rain’ — the type of work that makes you wonder why they just didn’t bother with a straight-up cover. Perhaps the most out-there moment comes with a bit of minimal murkiness that could almost be something from 1981 on Rough Trade, called ‘Nice’. That the band was called Crocheted Doughnut Ring just makes a certain sort of sense.

Then there’s some honest to goodness rarities here, nothing absolutely groundbreaking or a lost treasure, but things that could appeal to the scholar of the era. Thus, there’s George Alexander’s original demo for ‘Dear Delilah’, which took to the charts the following year as part of the group Grapefruit. Meanwhile, the story of the Brood’s ‘Village Green’ involves the Kinks, The Who and a car dealership, but the demo itself is a enjoyable little fillip that might as well have been a formally released track. Other demos and one-offs from other acts crop up throughout, though when it comes to a random number showing how ‘psychedelia’ as such had sunk into wider consciousness, it has to be the flipside of a Queens Park Rangers fan group’s football single, ‘Supporters — Support Us’, where a bog-standard enough chant slowly turns into a slightly lo-fi but still engaging rumble with heavily-reverbed vocals mixing grunts and yelps with praise for Rodney Marsh. Not quite prototypical acid casuals, I’d guess, but still.

Not everything works and not everything could, and more than once you’re all too easily reminded that these are a bunch of young and not always fully aware white English dudes who can try but not always succeed at whatever they’re aiming for. Some of it is sex goof level, like the Fresh Windows’ ‘Fashion Conscious’ or the Uglys’ ‘And the Squire Blew His Horn’, which perhaps half invents Prince Charming-era Adam Ant. But there’s more than a few songs about girls doing things they shouldn’t (ie, not with the singer), the previously mentioned Honeybus song is mostly about how a guy seems to be doing a “little child” a favor by sleeping with her, and if there is a female vocalist, much less a performer, at any point throughout the collection, you could have fooled me. If there’s a standout ‘uh’ moment, Tintern Abbey’s demo of ‘Tanya’ is it. It’s musically lovely, a gentle bit of semi-acid folkishness, but the lyric about an East Asian woman who “has left her cherry blossom land/for her noble Englishman”…well, maybe just stick to a song from The Mikado if you must. (Separately, I’ll let Skip Bifferty’s ‘Schizoid Revolution’ slide because the liner notes indicate its writer had worked as a psychiatric nurse.)

To conclude and return to an initial point, there’s a great sense throughout, whether talking about performers like about half of Deep Purple, producers like Tony Visconti, already struggling bands like the Searchers and more, of the chancers, the strugglers, song-pluggers and try-anything-that-works brigade, perhaps underscored by the appearance — once as songwriter, once as part of a larger group — of the ultimate chancer, David Bowie. (His 60s into 70s companion in that regard, Marc Bolan, also takes a bow with an inevitable choice, his standout from a short stint in John’s Children, ‘Desdemona’.) The first CD features Bowie’s ‘Silver Tree Top School for Boys’ given a merry enough reading by the Slender Plenty, while the second features the man himself in one of his more shadowy musical moments, appearing as part of the collective the Riot Squad with his utterly obvious and absolutely hilarious (intentionally…one hopes) reworking of the Velvet Underground’s ‘Venus In Furs’, ‘Toy Soldier’. In a year where we’re still taking in the loss of Bowie and so many others, it’s strangely relieving and inspiring to go back almost fifty years to a point where he was just trying to ride the groovy, hazy and trippy waves as much as everyone else seemingly was. And points for trying.