In 2006, while in recovery from cancer, Kylie Minogue talked to Another Magazine about her love of Grey Gardens. A 1976 documentary by the Maysles Brothers, the directors who made The Rolling Stones’ Gimme Shelter, it traces the eccentric lives of Big Edie and Little Edie, a socialite mother-and-daughter living in a run-down mansion in America, teeming with rubbish, raccoons and fleas.

Minogue watched it obsessively with her mother in Paris as she slowly got better. She said to Another: "There is a singular and extraordinary love between a mother and daughter – between my mother and I… we waded through trials, tribulations and tears, but we also laughed, a lot, like Big and Little Edie in Grey Gardens, spinning in a world of their own." The love between a daughter and her mum was love at its most obvious and mysterious, Kylie added, where "necessity and limitation gave way to delightful surprises." Then came an even more existential, un-Kylie line: "The ability to simply be."

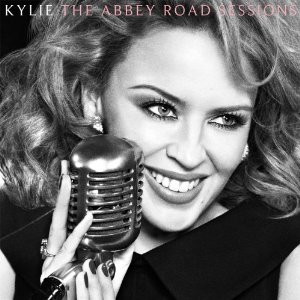

This year, Kylie’s career – not Minogue’s, it’s always Kylie’s – turned 25. Oh, 25…it’s a funny old age, a place where a person pivots between youth and the arrival of adulthood. Kylie’s career, similarly, still wobbles on that join. Should she be a sparkly prima donna with permanently surprised youthful expression? Or a dignified torch singer as this new project implies? Actually – roll it back – why am I asking this question anyway? It isn’t right that we ask older women in pop to settle into a role, surely, but we do. People knock Madonna for writing kids’ books and flaunting her body (I’d criticise her for other things, but that’s a different story). And surely we don’t want Kylie posing coquettishly, but also being middle-aged.

What I do find weird is that women have to pretend, and present, as if they’re young, when they’re long past that time of their life. Men also don’t present themselves sexually, or have to, after passing the big 4-0. Think of Madonna and Kylie’s 80s equivalents. You barely see Prince with his top off these days, do you, when you see him at all. Nor do you see Simon Le Bon with his shirt undone to the waist. Yes, you do see Morrissey unbuttoning his nylon shirts during his encores, and throwing the sweaty stuff into the crowds. But Steven Patrick doesn’t exist in the same, shiny, swirling pop world as Kylie. Kylie’s in a different place. And now she’s confronting her past in it.

I brought up the story about Kylie loving Grey Gardens because it offers a curveball to those who have a simplified vision of her: here’s the intelligent, thoughtful women behind the gorgeous, bubblegum pop girl. Of course pop stars can have depth, too, I’m not arguing against that – Bowie, the Beatles, and many others, made it part of them. Also, Kylie’s quotes to Another, although obviously stylised, offer a rare glimpse into her personal life, and a little golden detail about her solid, Welsh mum (I admit that her having a Welsh mum, like I do, has tickled a personal interest).

But what also frustrates me as I read this piece, as a journalist, is that I’ve also heard how hard Kylie is to interview. I know one women’s magazine who turned her down as a cover star a while ago because she always revealed too little about herself. This is a massive pop star who has beaten cancer, had a rock star ex-boyfriend who may have died in an auto-erotic accident, became famous playing a mechanic, got her head caved in with a rock in a song, and brought back sparkly hotpants. There are so many colours and shades within her, but they are rarely revealed. Naturally, I understand the appeal of mystery if you’re a celebrity, and the call of self-protection, too.

But in pop music, there is also endless potential to excite, inspire and challenge your audience, and the best pop stars have always had those qualities within them intrinsically. These are the qualities Kylie’s not let herself unveil, very often, to her public in the last quarter-century.

Slowly but surely, she’s showing them now.

The big reveal started this summer with a brilliant single, ‘Timebomb’. Time was "ticking so fast"; Kylie wanted to dance "like it was the last dance of my life". Yes, the song had a simple premise – it was basically about shagging someone. But at its core, there was an urgency about getting older, even stronger than it was on ‘All The Lovers’, the lead single off her 2009 album, Aphrodite. On that, Kylie tipped a wink to "all the lovers that had gone before".

Then came Kylie’s role in Holy Motors, a French fantasy film, in which she sang a torch song along through the corridors of a derelict department store. "Who were we, when we were who we were, back then?" she sang. She called her time playing brief role in it "one of the best moments of my life". The Abbey Road Sessions goes further, allowing Kylie to revisit her back catalogue with similar knowingness. Re-recording one’s old songs in an older style isn’t a revolutionary manoeuvre, of course – Bryan Ferry’s done the same this year with his Roxy Music-gone-charleston record The Jazz Age, while Robbie Williams’ Swing When You’re Winning remains a best-selling benchmark of the form (two million copies sold in the UK in 2002, alack, alas).

Kylie’s addition to the tradition is also a fairly mixed bag. I had high hopes for the LP after falling for her torchsong twist on ‘I Should Be So Lucky’, first performed on the 2009 Hootenanny with Jools Holland (Come back! There’s zero boogie-woogie in it, my brethren!) That performance is revisited here on one of the album’s best tracks, which takes a tune so embedded in our collective pop memory, and gives it a darker, desperate sheen. "Dreaming’s all I do, if only they come true," Kylie sings, with subtle feeling. It’s a treatment that makes you think about what it must be like to live in a world so driven by fantasy, and how reality can so quickly cut in, and cut out.

It’s also nice that the man who started the critical rehabilitation of ‘I Should Be So Lucky’ – Kylie’s fellow Australian Nick Cave, who got Kylie to read its lyrics at the 1996 Albert Hall Poetry Olympics – also appears on a re-recording of their 1997 duet, ‘Where The Wild Roses Grow?’ This time round, Kylie tries too hard to give her lyric extra portent, though, breathing too heavily on the song’s final notes. Nevertheless, there is something oddly moving about hearing the pair together again, thinking about the sixteen years that have passed, how their lives have diverged, and the bloody obsession with youth lingering in the murder ballad structure.

There are several other highlights. 1993 disco-monster ‘Better The Devil You Know’ – a song which I have to play when DJing, otherwise the world will cave in – is given a simple, piano-drizzled makeover, the bouncy optimism of the original replaced with a wearier, slightly Kurt Weill sort-of-shadow. ‘Confide In Me’ is also a joy, but then again it always was. Not many comeback singles by pop stars in the 90s began with a full minute of instrumental, Middle Eastern mysticism, and wild, woozy strings in a doomy minor key. On this version, the mood is sparser but just as mysterious, with slow, thudding drums recalling the trip-hop echoes of Massive Attack’s Mezzanine.

Other moments often feel like misses, though. ‘Finer Feelings” string-laden intro suggests it’s about to enter Bjork territory, but it never quite makes the plunge. Kylie also forgoes the high notes that originally made the chorus of ‘I Believe In You’ really soar; its magic wanes as a result. ‘Can’t Get You Out Of My Head’ also doesn’t respond well to this treatment, nor does ‘Slow’. Futurist-pop at its best, being ageless and robotically glamorous, rarely does, unless someone twists the material in an very unexpected way (see Tony Christie’s old-man-looking-back-on-his-life-take on The Human League’s ‘Louise’).

The tracks that say the most here are ‘The Locomotion’, ‘Never Too Late’, and Kylie’s newest single, ‘Flower’. The first takes the memory of Kylie’s first chart success, a cover of Little Eva’s 1962 single, and takes it sound back to its girl-group-flavoured roots. Kylie’s vocal embraces the song’s history brilliantly, just as she seems to be embracing hers. ‘Never Too Late’ – one of Kylie’s perkiest Stock-Aitken-Waterman numbers – gets turned into a gentler, more intimate statement. "It’s never too late, we’ve still got time, it’s never too late, you can still be mine," the line shimmers. The placing of this track at the end of the album can’t have been done unknowingly. It may have been a sentimental ploy, but the song comes across like a gentle, loving call-out to fans.

‘Flower’ is the only new song here, but it suggests new directions. A track left aside from Kylie’s 2007 album, X – her comeback album after recovering from cancer – it was later performed on the tour supporting the record, and Kylie has talked about its cult status among her fans. It’s easy to see why. Its sound is soft, gorgeous and intimate, its lyrics are older, wiser, murkier; Kylie sings of someone "wrapped in a blanket", a "distant child blowing in the breeze", and how "two hearts [are] in the hand of time". Many critics thought the lyrics could be references to her last chances at motherhood, an easy assumption for women so often measured by their body-clocks. I hear differently: an artist nodding to herself as a daughter, to that special relationship with her mother, to her vivid knowledge of time passing, and how that time can be used, and used well.

"Breathe life into me", the song goes, as you hear Kylie breathing new life into her career. Twenty-five years in, she’s enjoying that world of her own, and trying to help us enjoy it, too.