What a strange beast this is! Regional Surrealism is a disjointed, disorientating patchwork put together over five years, a bewildering Jekyll and Hyde of a debut that you can cut in half and divide between day and night… or daydream and nightmare. Perhaps that’s to be expected, because Konx-Om-Pax represents both sides of Tom Scholefield’s creative output: he makes both riotous, strange sound, as well as drooling, delirious animations for the likes of Martyn and Lone, both under the same name.

The spooky sketches that make up Regional Surrealism‘s first half don’t exactly evoke daytime so much as some unnameably strange twilight, experienced through the fog of a tranquiliser overdose. Demented sci-fi music, haunted sounds for sleepwalking children, and something like Boards of Canada feeling sickly at the funfair: all drift through this colourful wilderness in a mood weirdly between cheer, boredom and fright. And it feels exciting at first, but listen more closely and you find a curiously vacant kind of music – holographic tracks that seduce but stay strangely forgettable even after a month of sustained listening, simulating the excitement you might find in other, spookier electronic sounds. (Music has the right to children, but I wish they’d be a bit more monstrous and adolescent, less well-behaved, less careful…).

If you’d heard his two recent mixes of luscious house, techno and old-skool rave (one for The Quietus, and another made with Rob Data) and are familiar with his fascinating, otherworldly animations, you might have expected a more adventurous kind of music. On the album’s first half, everything sounds correct but lacks any intoxicating, addictive spark. Consider the dextrous selection in those mixes, or his approach to visual art, and you might expect some rare and bizarre beast to be born, some new region of sound to be carved out, an astonishingly weird, luminous synthesis of rave fantasy and electronic dystopia. Or, taking the title at its word, imagine a tryst through illicit sexiness, perverse textures and unholy juxtapositions. These records will have to remain dreams, although it provides vague maps of both, hazily drawn.

When its mood alters, somewhere around the metal wasteland of ‘Lagoon Leisure’, and things start getting sinister, then Regional Surrealism becomes (finally) exciting. The record transforms into a deeply disconcerting experience, all eerie shadows and claustrophobic spaces. Play it in the dark and you start having visions. It messes with your skull, this kind of demonic musique-concrete full of unexpected explosions, synth flashes, groans, shivers and howls. You can’t find your way around it easily. I had to invoke the ghost of the Great Beast to help me.

You see, there’s a third Konx-Om-Pax, a strange, arcane text by the ‘wickedest man in the world’ Aleister Crowley, written at the start of the last century. In its pages, the magickian describes the dark and haunted space of this record with uncanny accuracy. His heroine, Lola Daydream (think Carroll’s Alice, but senseless, doe-eyed, bewitched by boys) enters "the strangest house you ever saw", and soon finds herself staggering down a "frightfully dark" tunnel, full of "the strange dreams and awful shapes of fear". That’s where you are, too – inside the haunted house, lost in the dark.

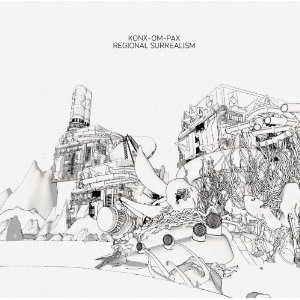

Strange and haunted houses are significant symbols in this album (there’s one on the record’s cover, obliterated by a sci-fi monster (that’s Scholefield’s most obvious surrealist gesture, a sort of ‘Max Ernst in industrial America’ thing). I started thinking of some others: the fantastical ‘sound houses’ in Francis Bacon’s The New Atlantis from 1627 where "strange and artificial echoes" can be heard that transform sounds so they return "louder, shriller, deeper" than they came. It was this description of the recording studio and its transformative power, three hundred years before its existence, that enticed Daphne Oram into her experiments with electronic equipment and involvement with the BBC’s pioneering Radiophonic Workshop.

The latter half of Regional Surrealism feeds back into that spiky, sickly feeling you get from early electronic music, the industrial witching hour atmosphere with its high frequencies, murderous stabs in the dark and comet-like shrieks. It constructs a terrifying, haunted sound house. The toxic fumes and hum of deep disquiet that drifts through Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works II are also a presence here, too: Regional Surrealism is similarly attuned to sinister resonances and unearthly noise. After its release, the mischievous Richard James told of nights spent wandering round power stations, modeling tracks on their constant hum, which he said put him in contact with "a strange dimension". Occult activity indeed.

Fear and horror are megaphoned through or buried just beneath the surface of a great deal of music at the moment (there are dozens of dystopias, many prolonged periods of darkness, endless anxieties about the apocalypse; a mass of sinister noise drifts through the air). Their sudden appearance here feels less knowing than with many of Scholefield’s contemporaries – more immediate and more unnerving, because the sounds remain unfamiliar. They seem to come from the underworld, rather than a piece of software.

At the end (as always) light returns, and it concludes in the same bright world as before with ‘Let’s Go Swimming’ (I imagine a cover of the ectoplasmic Arthur Russell track) where woozy synth coalesces gloriously to begin one final flight, then vanishes: a theme song for a sleepy sort of joy. I wish there was more menace, but maybe there’s more than enough. Nightmares are much more difficult to shake than dreams.