You feel that? A disturbance in the bass-time continuum. Maybe it went unnoticed because it’s something so old, so true, so certain, that we’ve come to take it as a given. The sun will rise tomorrow. Capitalism will prevail. The establishment will remain established. You will always be broke. The clock in the kitchen will make you miss your morning train even though you know it’s four minutes slow and yet you still can’t be fucked to get up on the counter to adjust the thing. Shit will happen, because it always has and always will. And just like all these inevitabilities, there will always be a unified dance scene to get behind – something we can all latch on to and agree upon. There will always be an endless well of inspiration that rejuvenates itself every few years in the form of hardcore, jungle, drum & bass, garage, grime, dubstep… It’ll be like this, always and forever, until the universe reaches maximum entropy and swallows us all.

But wait, hold up, hold up, spin it back. What exactly is that you’re playing there, mate? I mean, what’s it called? ‘Cause last time I checked it was all about the dubstep. You know: Mala, Benga, Pinch, Skream, Burial, that one geezer from Scotland? So what are we calling this again? What’s the tempo? Where’s it coming from?

The answers have been there since the early days of rave. The ’90s and 2000s were characterised by a steady procession of dominant genres bowing out as each exhausted its course. But since the dawn of the decade it seems this natural progression hasn’t so much slowed as scattered, split, dissipated into countless micro-scenes helmed by individual developers attempting to carve their own notch into the woodface. The all-consuming rise and eventual decline of dubstep has left a gaping hole in the fabric of dance with no one true contender fit to fill it. It seems that the once-heralded (and here’s a term I haven’t heard bandied about in a while) ‘hardcore continuum’ no longer consists of a clear linear path, rather a mycelium of branches reaching, twisting and wrapping around each other, helped in no small part by the proliferation of the online global village.

From trap to afrobeats, juke to jackin’ house, 2013’s bass topography is dizzying, spanning not just a handful of London postcodes but entire continents with artists from all camps happily swapping remixes and collab work. The advent of Soundcloud has levelled the dance marketplace, allowing anyone in the world to access tunes from anywhere else, be the artist well-known or small-time. The idea of a homogenous subgenre like jackin’ house in Leeds or footwork in Chicago staying within the confines of their respective cities seems highly unlikely today. Even the 140bpm massive started experimenting with 4/4 beats a few year ago, spawning techno/house hybrid guys like Pangaea, Blawan and Mosca. There’s a wind whistling through the pigeonholes and it’s giving purists a severe crook in the neck.

Someone who in theory ought to be running scared from all this is Steve Goodman aka Kode9. After all, wasn’t he the guy who made his name as one of the major boosters of dubstep back in the 2000s, when people knew where they stood and a spade was a spade? The Kode9 brand was originally synonymous with the kind of weighty, eyes-down atmospherics pioneered by the original dubstep merchants at nights like DMZ and FWD>>.

In truth, though, Kode9’s been playing and documenting bass music since well before dubstep even became a thing. A junglist who came to the capital from Glasgow, Goodman never bought into the tribalism surrounding the various North/South/East/West London divisions, allowing him to spin whatever tunes he wished without worrying about where they came from. As a scholar and a voracious fan of the music he works with first and foremost, Kode9 is anything but a purist.

When dubstep went supernova towards the end of the decade, his Hyperdub label remained a sanctuary for those who preferred the relatively exploratory, no-nonsense (albeit highly innovative) branches of funky, grime and broadly speaking ‘post dubstep’ over the boorish grind of Rusko or Skrillex. And the label has been venturing well outside its earlier arenas for some time now, with the likes of Terror Danjah, Laurel Halo, Funkystepz and Hype Williams all key figures within the label’s roster in the last couple of years. More recently Hyperdub followed in Planet-µ’s footsteps, becoming the second major UK electronic label to champion the Chicago footwork sound by releasing DJ Rashad’s Rollin’ EP, further cementing that genre’s legacy.

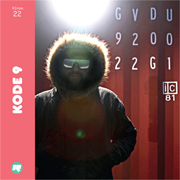

Nevertheless, Rinse:22, the third commercially-available DJ mix from Goodman, may come as a surprise to those more attuned to the darkly shifting undertones heard on his last solo release, 2011’s Black Sun album. This is, by contrast, a breakneck joyride through the 2013 dance macrocosm with every conceivable permutation of bass-driven music torn through at a rate of knots.

The only residual murk comes right at the beginning, in the shape of Burial’s ‘Truant’, comfortably setting the scene in typical Burial style before morphing into Prodigy-esque rave as heard from the next field across. The deep jittery funk of Theo Parrish’s ‘Kites On Pluto’ wouldn’t have sounded out of place on 2009’s 5 Years of Hyperdub, a compilation showcasing that era’s generation of dubstep-borne experimenters. However by the time we reach Alex Parkinson and Chris Lorenzo’s excellent jackin’ house hooter ‘What Must I Prove 2 U’, it’s clear we’re being steered well away from the moody meditations of yore. The opulent big-room production of Funkystepz’ ‘Vice Versa’ comes hot on its heels, with barely pause to consider a brief snatch of Joy O(rbison).

As platter after platter hit the floor, so too do genres. A flurry of cuts from Terror Danjah, DVA, Champion and Jam City come in a rapid succession whereby grime, UK funky and trashy neon house are fused into a nameless but ferocious hybrid. Things hit full throttle with Dexplicit’s grimey shoot-em-up ‘Change Formation’, by which time BPMs are reaching the higher numbers. Things really don’t stay still for long, with few tracks staying in the mix for more than a minute or two. Yet there’s a lot to be said for Goodman’s expert use of space and arrangement. There are indeed moments where Goodman will take it down a notch, as on Cashmere Cat’s queasy trap inspired meltdown ‘Aurora’ or the slow/fast iciness of Kuedo’s ‘Mirtazepine’, but these are employed only as short contemplative segues to allow the mix (and hopefully dancers) to catch some breath.

The overall effect is never cluttered, and neither does the mix ever feel like treatment to an exercise in genre-hopping. Everything is blended with such deftness that, despite prompting a wish for certain tracks to hang around a little longer, it feels like we’re being shown a snapshot of exactly how colourful and coherent the current musical landscape really is; grand unifying dance style or not.

Goodman has in recent interviews expressed a wish to get away from the “sluggish, plodding and rhythmically boring” aesthetic that has come to characterise electronic music. That re-emergent interest in faster rhythms is put into practice during the final third of Rinse:22, in which the style switches to the current Hyperdub fixation of Chicago footwork. The section includes cuts from scene stalwarts RP Boo, DJ Manny and DJ Rashad (including two tracks taken from the latter’s debut release for the label), as well as non-Chicagoans taking cues from the style such as Addison Groove and Bleep Bloop. Most notable are ‘Xingfu Lu’ and ‘Kan’, Kode9’s first forays into the genre and his first new productions in 2 years. ‘Kan’ in particular shows off his dexterity as applied to this new approach, the track’s 160bpm bicycle chain rhythm set to a rising steam kettle shriek that takes the genre’s pressure cooker vibe to its literal conclusion. We end with Rashad’s ‘Let It Go’, itself a hybrid of footwork and jungle, and one of the best examples of genre cross-pollination witnessed this year.

Music fans accustomed to tuning in on a particular rhythm or style might bemoan the current musical climate and its lack of identifiable direction. Rinse:22, by contrast, proves that within the morass of interzone bubblers, international ambassadors, ageneric misfits and old heads working to a new beat, the current dance music scene is as extraordinary and vital as it’s ever been.