Los Angeles-based Stones Throw didn’t invent the breaks record, but the label has taken the concept and run with it. Their latest find, Detroit beatmaker and jazz drummer Karriem Riggins, has produced what could be the antidote to too much anodyne and predictable beatmaking coming from the US.

Riggins – his real name – is something of an unsung hero, popping up Zelig-like on hip-hop records by Common, Slum Village and Erykah Badu. He’s also a full-on jazzer, playing the drums with combos like the Ray Brown Trio, and working with Paul McCartney on his recent Kisses On The Bottom record, and has even toured with Diana Krall.

For his debut, he produces a sprawling and inventive set of beats that begs the real question: When can he be paired with a killer wordsmith?

Breaks records were originally produced as ‘DJ Tools’ – records for DJs to muck about with to show off their scratching ability or make blends – sticking an acapella of one record over the breaks from another to impress the crowd (or not). Such records would contain loops of notable breakbeats, the kinds of ‘bonus beats’ you might find towards the run-out of disco 12-inches, special beat and bass-heavy mixes, or looped funny noises with beats on top.

Breaks records are often not even real albums, but literally collections of loops, so of limited interest to the record buying public. Stones Throw released one of the first big sellers, Super Duck Breaks by Lootpack’s DJ Romes (credited as Turntablist), and the label has gone on to change the image of the breaks record by putting out records by the Tortoise rhythm section (the incredible Bumps in 2007), in addition to dozens of albums by the one-man breaks factory – Madlib, who has three entire series of breaks albums.

Riggins has a varied repertoire, with a clutch of solid head-nodders like ‘Stadium Rock’, ‘Esperanza’ and ‘Harpsichord Session’ sitting alongside more experimental 303-infused numbers in a Dilla or Flying Lotus style like ‘Water’, ‘Up’, ‘Back in Brazil’ or ‘Voyager/500’, which has already attracted the attention of producers like Mark Pritchard, looking for what’s next post-dubstep. Riggins also has a series of overtly jazz productions such as ‘Double Trouble’ or ‘Ding Dong Bells’, and some that sound like they are recorded in a smoky club between jams (‘Live at Berts’, say) in addition to the inevitable skits and spoken word outtakes.

From the off, the record is infused with the sound of the MPC – in itself refreshing as so many producers have ditched making their beats on The Box to use computer-based set-ups like Ableton or Logic. Classy MPC workouts like ‘No Way’ and ‘Bring That Beat Back (next time)’ show why this is a much-missed medium.

Dominating the album are a few instrumentals screaming to be a bit longer. ‘6-4’, at just 31 seconds, is simply not long enough, with a slacker-than slack beat, rumbling bassline and simple keyboard riff coming to an abrupt end.

‘Moogy Foog It’ follows a staccato 303-line and beat for 90 seconds with occasional synth washes and recollects something from The Neptunes’ heyday. ‘Stadium Rock’ sounds like a lost rock break with rubberband bass and handclaps looped to perfection for little more than two minutes. ‘Esperanza’ showcased a summery and dare I say it cheeky trilling flute riff for 90 seconds.

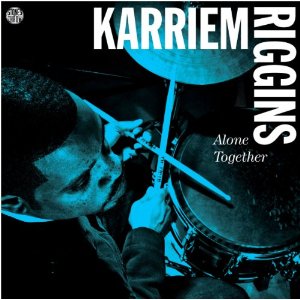

Stones Throw have done a fine job here, and I await the next Riggins productions eagerly. Even the cover art looks great, with Together featuring Riggins on his drumkit in a way reminiscent of Art Blakey’s classic Blue Note releases. This is a record that leaves you wishing for one thing more, though – some of these beats seem too good to be used on an instrumental, and could stand up handsomely against a powerful wordsmith. Stones Throw has a few on its roster (DOOM – perhaps a collaboration is inevitable? – or Percee P, whose Madlib produced debut underwhelmed), and it’d be nice to hear the material that makes Alone Together such a strong release alone no more.