Recently, after a regrettable trip to see the Razzie-baiting Batman vs Superman, my companion turned to me and said something I never expected to hear [SPOILER ALERT]: "If I see Neil DeGrass Tyson appear as himself in one more film," he told me, "I am going to join B.o.B’s flat earth conspiracy cult out of pure spite".

Despite my mostly platonic affections for the well-moustachioed physicist, I could see that my friend had a point. Every respected authority can only make so much capital out of the goodwill of their fans and acolytes before the same qualities that attracted fame and fan fervour in the first place become causes for derision. This is doubly true when it comes to career resurrections, revivals, reboots, resurgences and reunions, which is why another year without any new material from the Stone Roses should end with a brutal and protracted Merseyside lynching.

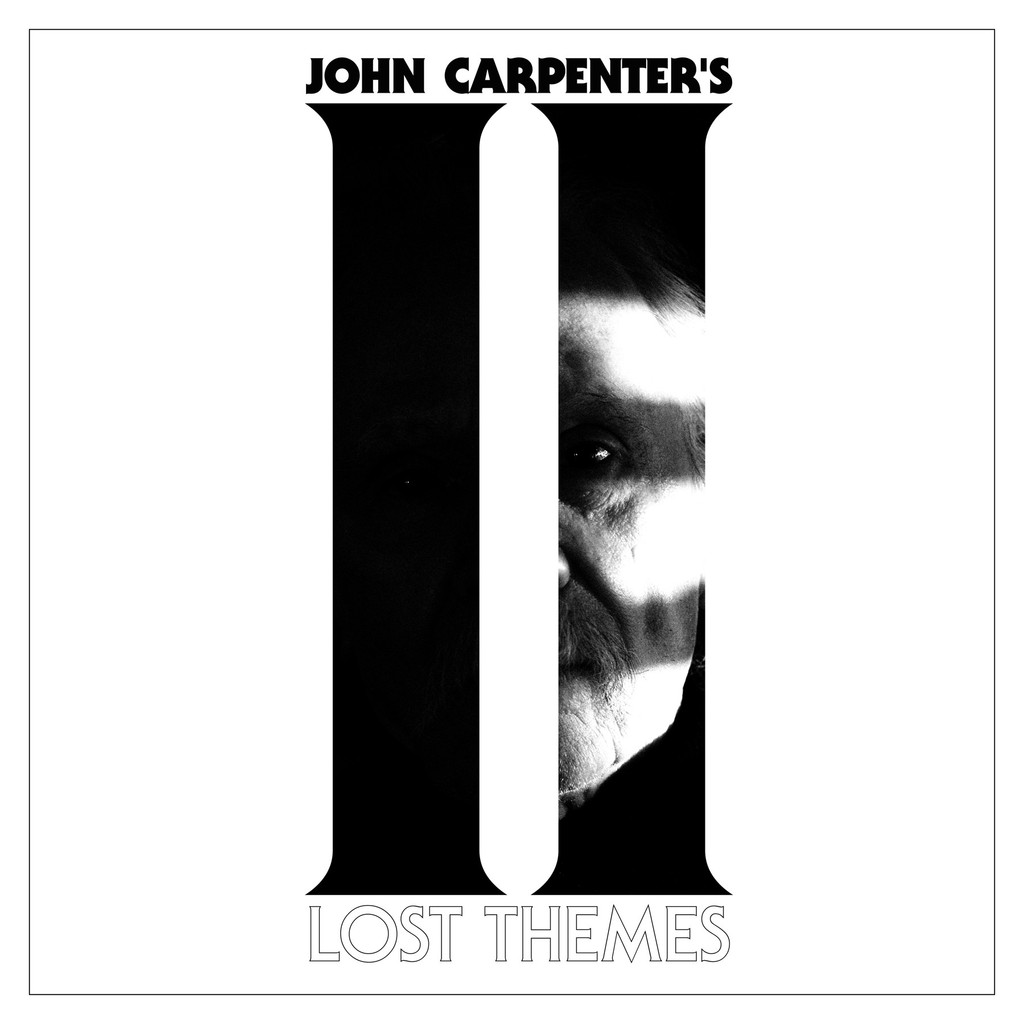

It has been a long time since director, composer and all-round Renaissance man John Carpenter, from whose mighty cranium strode a host of cult classics that included The Thing and Escape From New York, has been the subject of derision. The increasingly dire remakes of his work that Hollywood excretes only serve to enhance his status as one of the greatest visionaries in both cinema and soundtracks, his reputation swelling to the point that now even his objectively shoddy 90s output is defended as ‘cult’. He could have lived out a long and well-earned retirement watching his corpus of work amass more reverence than it ever achieved during his working lifetime. Instead he took the unexpected decision to return to the public sphere in his secondary capacity as a musician. The start of 2015 saw him emerging from the abyss to release his debut non-soundtrack album (the aptly named Lost Themes) at the tender age of 68 before triumphantly performing at ATP and winning over a new generation of fans in the process. Or so the narrative goes. In reality he actually resurfaced in 2010 with a dreadfully trashy film called The Ward, but the world seems to have collectively forgotten that.

I only mention The Ward when discussing new album Lost Themes II because it showcases John Carpenter’s enduring ability to produce pure detritus on occasion. Taking the long view of things, this doesn’t matter too much to his legacy as a director: film is a format far more forgiving of failure than music and many of Carpenter’s misses still take the ‘so bad it’s good’ consolation prize. But, while his directorial output has had its share of troughs alongside its peaks, his talent as a composer has remained largely unsullied (his soundtrack to the otherwise awful Vampires remains one of his greatest works).

Lost Themes II gambles with this legacy, opting far too frequently for lazy twiddling around the devil’s interlude rather than stacking up the kind of top-shelf synthscapes that speckled Halloween and his musical magnum opus They Live. Though opener ‘Distant Dream’ boasts a visceral drumbeat, its half-baked attempt at industrial heft leaves Gary Numan’s Dead Son Rising looking like Nine Inch Nail’s Pretty Hate Machine, while ‘Last Sunrise’ sounds like one of Nintendo’s more tepid character selection themes. Recent single ‘Angel’s Asylum’ is cheesier than Robert Tepper’s wotsit-caked rider, which would be fine if it weren’t for the distinct impression that John Carpenter became the musical equivalent of George Lucas circa 1999, thought "My my, this loop is intense! The kids are going to flip their lids when they hear this shit!" and subsequently shut his ears to the advice of his collaborators (son Cody Carpenter and composer David Daniels) in favour of his faith in his own tried and tested methods. None of Lost Themes II is out and out bad, per se, but there’s nothing awesome here. A grand folly or artistic disaster from the Master of Horror would have been excusable; instead we get the ultimate insult of mediocrity.

Much like Devo’s underrated Something For Everybody, the first Lost Themes succeeded thanks to its pairing of an artist’s signature sound with an updated array of recording techniques and technologies. It didn’t matter that the album didn’t push any envelopes, the experience of listening to the colossal modern production on such compositional throwbacks as ‘Obsidian’ or ‘Purgatory’ justified the artistic validity of this unexpected comeback. But John Carpenter used to push music forward rather than throw it back. For Lost Themes II to deserve the sales it takes from a new generation of upcoming electronic artists, it needed to prove that it’s maker had fresh ideas rather than unused leftovers. It needed to be a Blackstar, not a The Next Day Part 2. Instead we’re left with a lightweight affair that reminds us all that John Carpenter is far from infallible.