Jethro Tull are among history’s most misrepresented bands, with leader Ian Anderson regularly ruing their (randomly chosen) name and its connotations of finger-in-the-ear, cider-drinking, beardy folk rock. Yes, they made a couple of albums that perhaps fell into that category. And OK, they had beards and dressed like a bunch of country squires. And granted, the agrarian bluesiness of Anderson’s voice is a bit of an acquired taste. And his main instrument is the flute. But, this is all beside the point. Because Jethro Tull produced some of the most absurdly inventive, lyrically scabrous and surprisingly rocking albums of the 1970s. And A Passion Play may well be their finest 45 minutes.

Not that the band would necessarily agree. Coming off the back of 1972’s hugely successful Thick As A Brick, a piss-take of the concept album that still managed to have its cake and eat it, the band de-camped to the Château d’Hérouville studio in France to record its follow-up. However, things didn’t go well due to a combination of technical problems, food poisoning and homesickness (Bowie would experience similar when he recorded Low there), and on returning to England, Anderson decided to scrap what they had and begin again, writing and recording a new album in less than three weeks ahead of a major US tour. Like Thick As A Brick, A Passion Play was another continuous suite of music, but unlike its predecessor, its bearing was less jokey and more serious – it certainly wasn’t straight-faced, but its combination of kitchen sink mysticism and complex musical arrangement produced an album that still sounds joyously challenging even today.

Released in 1973, there’s some interesting parallels with that year’s biggest record, Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon. Both are concept albums that look at the choices we face in everyday life, with big themes including religion, class and death. They also both begin with the sound of a heartbeat. But despite both bands being major players in the prog world of the day, there are big differences in approach: the Floyd intro seamlessly segues into Dave Gilmour’s flanged guitar and mellifluous vocal, the aural equivalent of a warm bath, while the Tull pulse abruptly turns into a knowingly ridiculous parade tune, Anderson as the Pied Piper leading the listener into a place of uncertainty and limbo. And while Roger Waters neatly demarcates his ideas, Anderson creates a sprawling anti-narrative full of wordplay and allusion, but also genuine poetry.

A Passion Play follows its recently-deceased protagonist on his journey through the afterlife, including encounters with both God and the Devil – it’s like Dante’s Inferno or Milton’s Paradise Lost reimagined as a theatrical performance put on by the local Rotary Club, laced with satirical humour and snarky asides. (Wikipedia has a reasonably cogent overview of A Passion Play‘s storyline, but there’s serious analysis elsewhere for the hardcore fan.) In fact, there’s an argument to be made for the Tull of this period being a musical equivalent of Monty Python, daft but clever in equal measure, though with the Oxbridge surrealism replaced by a northern end-of-the-pier earthiness (the band originally hailed from Blackpool).

But it’s the music that really makes A Passion Play stand out from the prog pack, a maddening onrush of stomping riffs, dense instrumental passages, pagan dances and acoustic interludes. There’s an extended sound palette too, with synths used for the first time and Anderson playing soprano sax, while his flute is multi-tracked to cosmic, disorientating effect… All of which might seem on paper like an archetypally hellish piece of prog indulgence, but the reality is something else. The music’s certainly complex, but it’s never noodly or difficult for the sake of it, and it’s clearly designed to give the listener maximum pleasure for their buck – unlike the psychedelic or classical background of prog royalty such as Yes, Genesis and ELP, Tull had their roots in blues rock, which may explain why even at their most obtuse, Tull never sound like they’re just showing off. Section (as opposed to song) highlights include the jerky demonic groove of ‘Critique Oblique’, the mounting tension of ‘The Foot Of Our Stairs’ and the exultant release of ‘Magus Perdé’. Oh, and there’s also ‘The Story Of The Hare Who Lost His Spectacles’, an Edward Lear-eque nonsense fable delivered in a fruity Lancastrian accent (check out the wonderfully odd and slightly disturbing film made to accompany this section in concert – it’s like Lindsay Anderson directing a Beatrix Potter ballet).

On its release, A Passion Play was not received well by the critics – but nevertheless, it still went to number 1 in the US charts. That may seem somewhat incredible at this distance in time, but after Led Zeppelin, Tull were the biggest UK live act in the States in 1973 – they put on a show, and like the aforementioned Python, American audiences responded in their masses to the parodically exaggerated Englishness on display. And while Anderson still has mixed feelings about the album, it’s a remarkable piece of balls-out musical theatre from an age when bands weren’t afraid to stretch their fans a little bit.

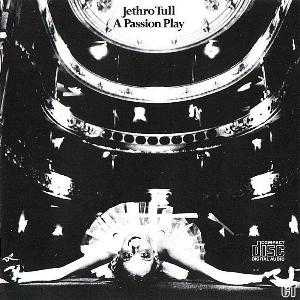

This latest re-issue comes nicely packaged as a novel-sized hardback book with lots of notes (there’s even an interview with the dead ballerina from the album’s striking sleeve). As well as A Passion Play itself, we also get the near-as-dammit complete Château d’Hérouville sessions for the first time (re-sequenced and superior to their previous release on Nightcap), with everything remixed by Steven Wilson, the hardest working man in prog. There’s a fantastic clarity to the sound now compared to the muddiness of the original mix, even if it’s a bit too clean in places. The one major change is the insertion of a "missing" 50 seconds into ‘The Foot Of Our Stairs’, which for me slightly spoils the previous dynamic and illustrates why it was taken out in the first place.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/15934-jethro-tull-a-passion-play-reissue-review” data-width="550">