Spiritual jazz has always been a fringe denomination. And it’s difficult to pin down for good reason; its name is less to do with the sound of this particular jazz, rather more that it’s jazz with a particular message – religious, political or both. Although more celebrated today, the cosmic messages chanted through Sun Ra’s music were previously seen as esoteric, perhaps occultish, with focus mostly being on his mental instability. But now, it’s this “spiritual” jazz that Ackamoor draws from the most: Sun Ra and Pharaoh Sanders are paid reference to in nods across his new album, We Be All Africans.

It’s strange that Ackamoor’s name is largely unfamiliar in Western jazz – he studied under the famous jazz pianist Cecil Taylor – though he left America to play across Africa, inspired by Ghana and Ghanian music: Fully respected and admired in Tamale, he played with the Tamalian king’s own musicians. In America though, his name would not be as familiar as Taylor’s or other musicians who played in bigger jazz bands where a reputation could more easily emerge as a result.

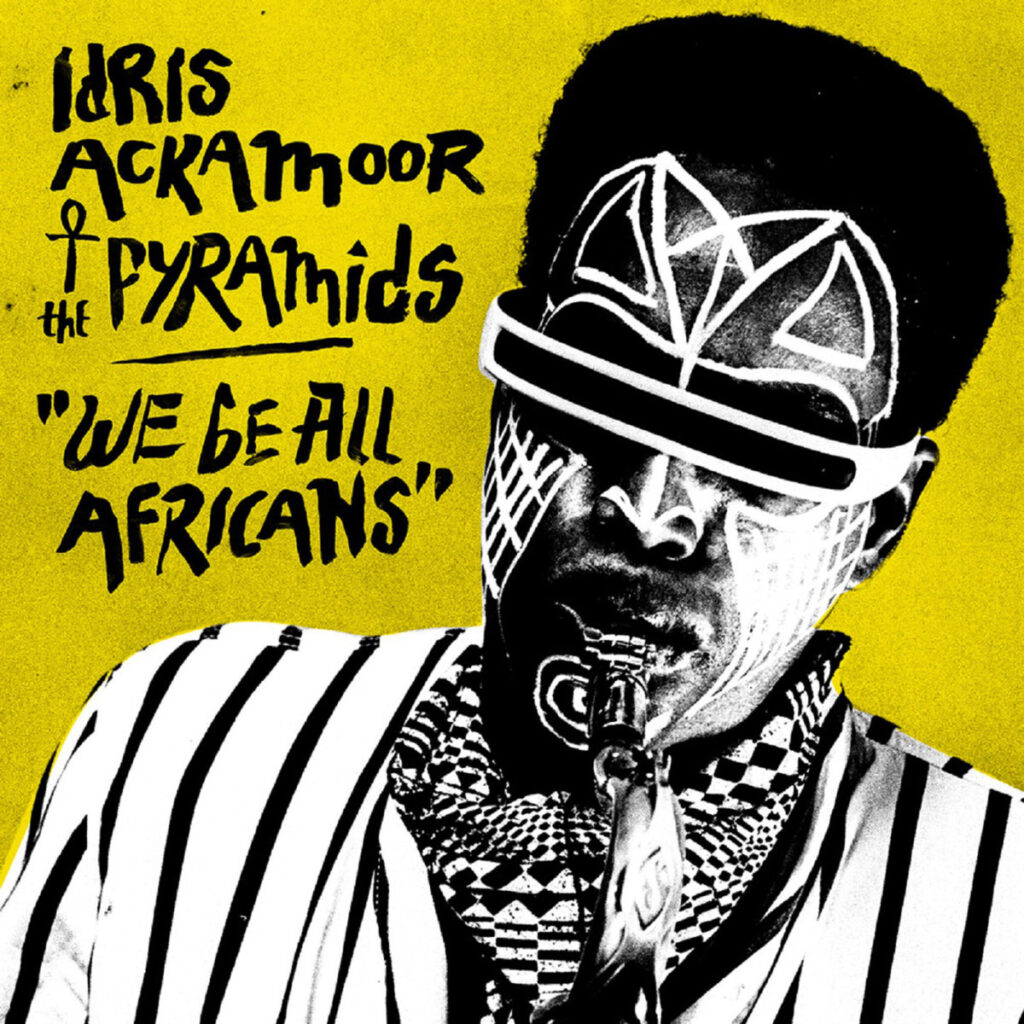

We Be All Africans is an interesting and loaded title. Like Sun Ra, Ackamoor buoys a serious message atop his playful melodies: Humanity originated in Africa, and so Ackamoor believes that this shared heritage unifies humanity; he thinks that divisions between race would be detrimental to the survival of humanity as a whole. His music then may be presented, in an ideal world, as something that can be respectfully appreciated by all. That is, as a joyous, cultural boundary crossing flip-side to racial aggressions and violence.

This album does not dully encapsulate what is familiar to previous jazz and Afropop records and instead is modern in the sense that it looks to more recent music and instrumentation for points of reference. ‘Epiphany’ unfolds with a slow, creeping electric bass and cool synthesiser phasing, counterbalanced with sharp horn stabs and clattering drum fills before returning back to the gentle introductory sway. Synthesiser might have been found on Herbie Hancock records or Sun Ra, but the phaser sound used here sounds more modern, despite having been recorded in Max Weissenfeldt’s analogue studio in Berlin.

If you’re looking for explicit Sun Ra references, you’ll find them on ‘Silent Days’. This third track features cosmic imagery familiar to the self-proclaimed solar explorer’s own records. Even the chanting has the same relaxed lull that Sun Ra’s Arkestra sometimes break into on his tracks. But ‘Silent Days’ is a gentle homage, and doesn’t serve to copy for copying’s own sake. And jazz has had a solid history of paying reference to previous musicians, usually mimicking their hooks or motifs: The comical, breathy yelps on ‘Rhapsody In Berlin’ are like those on Herbie Hancock’s ‘Watermelon Man’, but this helps to accent and maintain the pulse of a track euphoric on the surface, but not without chaos or aggression. It should be aimless sounding, but the cacophony works because of the way in which it is subtly built up: A violin makes a brief solo appearance, jazzy in the sense that the playing is very experimental in terms of timbre. The bow judders and screeches across the strings as if to damage them. When it gets to the stage where ‘Rhapsody In Berlin’ sounds overly busy, the band quietens somewhat – the trick to creating balance.

This album shows Ackamoor’s band, despite having an almost 30-year break, to be very comfortable with one another – in playing together. Unlike with indie bands or in pop music, in jazz it’s more common to find people who have played together for years before recording anything. The Pyramids listen to each other with almost as much intensity as the part that they are playing themselves; it requires the ability to hold back and add only a small amount to the overall piece as the musician sees fit at any given time. The musicianship here is self-aware but in a reflective rather than destructively fussy way. For instance, the violinist on this album only features from time to time, but if the violin were more present it would self-indulgently detract from the overall. ‘Epiphany’ in particular is full of restrained decisiveness, the mood completely under control of the band, and We Be All Africans as a whole has a joyous sentiment – loose and unrestrained by tensions.