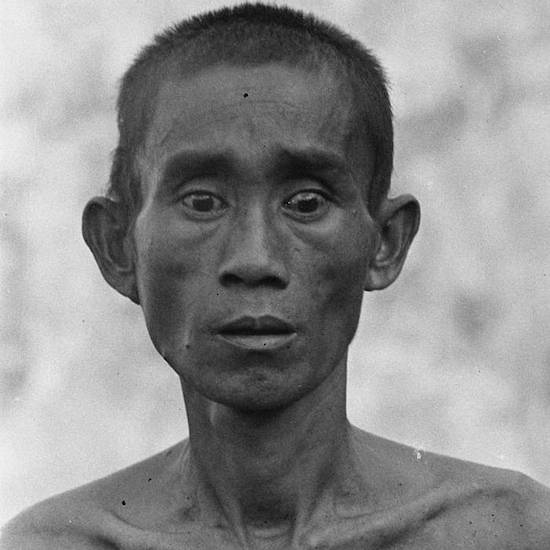

At the Troppen Museum in the Netherlands, 2016, Kasimyn of Gabber Modus Operandi stood in front of the cover of Bunyi Bunyi Tumbal. It is a black-and-white photograph of a man caught mid-reaction: eyes wide open, averted from the camera. The subject is credited only as “a man from east Java”. It is here that Kasimyn (real name Aditya Surya Taruna) adopted the name Hulubalang to imagine and notate the worlds of possibility that were only ever labelled as ‘anonymous’ in the numerous Dutch war archives he visited.

Roughly translated as ‘A Synthetic Feeling for an Anonymous Sacrifice’, Bunyi Bunyi Tumbal documents Hulubalang’s personal responses to these war archives. It is a difficult, brutal listen, but not for the reasons you might think. Though this is a reaction to the legacy of Indonesia’s turbulent relationship with war, there is little concrete reference to that history. That knowledge gap denatures the DNA of dance music, politics, and death in just shy of fifty minutes.

The album’s voyeuristic opener ‘Piso’ is an effective exercise in world-building; the mischievous gendang drums scamper alongside mangled voices that call out, only to be drowned out by thunderous drums and shrill synths. It is meant to represent a small, unknown village in Indonesia, suddenly exposed to the colonial forces that would soon disrupt Indonesia forever. This gives Hulubalang the permission to create all sorts of off-kilter rhythms, such as on ‘Kemaut’.

In many respects, the album is a sorrowful tribute to the unnamed victims of the war, creating spaces for them that expresses the rage of those who will never get to speak for themselves. All of the voice samples on Bunyi Bunyi Tumbal were chosen at random; none of the voices have any connection to the Indonesian wars themselves. That creates an appropriate emotional distance on songs such as ‘Cerca’, which centres around a motif of a garbled scream that constantly fights to be heard in the mix of gunshot snares and trap hi-hats.

But on tracks such as ‘Gendang Ria’, there’s a different portrait painted: the upbeat drums return, their dissonant overtones emphasised by square waves that create an absurdly jubilant melody. This is in reference to Balinese death rituals, or ngaben, where funerals function as a way for souls to be liberated. ‘Gendang Ria’, which translates to ‘happy drums’, expands the idea of death as simply mournful and something to be remembered, encouraging us to find some way of letting go.

The album also attempts to destabilise the binary of oppressor and victim. ‘Buddakkawan’ is a play on words: ‘budda’ in Malaysian is ‘buddy’, but in Indonesia, ‘slave’. The lyrics, written by author SaintMary, reflect this: “whose name is in history? Whose to blame?”, she screams. Seemingly, the album never answers this question, sitting in its uncomfortable uncertainty in its hammering kicks and vocals distorted into oblivion.

That is the album’s greatest strength, resulting in a sonic palette that is both sparse yet maximalist, where jagged polyrhythms emerge from hazy clouds of white noise. ‘Tungkai’ features ceremonial drums that boom in firework fashion; ‘Sayat’ is a punishing listen that accents every first beat with a malfunctioning laser sound. The industrial clatters that dance in the background are imaginative and moving, even if the moaning becomes slightly repetitive.

Bunyi Bunyi Tumbal is ambitious in every sense; technically masterful, conceptually complex, and emotionally potent. It refuses to hold back or to simplify its feelings, leaving us as perplexed and petrified as a man from East Java.